Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God investigates the secret crimes of a Milwaukee priest, Father Lawrence Murphy, who abused more than 200 deaf children in a school that was under his control. At the heart of the documentary is a small group of courageous deaf men – Terry Kohut, Gary Smith, Arthur Budzinski and Bob Bolger – who set out to expose the priest who had abused them and sought to protect other children. In addition, the film also spotlights similar sex abuse cases in Ireland and Italy, and shows the extent of the cover-up to protect the Catholic Church.

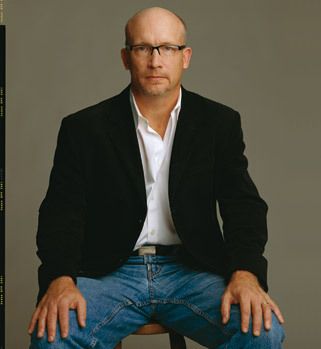

During this exclusive interview with Collider, filmmaker Alex Gibney talked about how this documentary came out, how they determined the film’s narrative structure, what most surprised him when he spoke with these heroic deaf men, the decision to have actors (Ethan Hawke, Chris Cooper, Jamey Sheridan and John Slattery) provide their voices, his reaction to the extent of the cover-up, and what it would take to change such actions. He also talked about another documentary he’s made about the abuse of power, We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks, and what he’s looking to do with his production company, Jigsaw Productions. Check out what he had to say after the jump.

Collider: How did this documentary come about?

ALEX GIBNEY: I read Laurie Goodstein’s piece in the New York Times, and it struck me as something horrific. But then, the guys who produced the film approached me and said, “You should think about doing this.” I was raised Catholic, and this was something that I had thought a lot about. I wasn’t sure what I could add because there had been other films made about it, but two things struck me that were important and made me want to do it. One was the fact that these guys were heroes. They may have been the patient zero case that was the first public protest that we could figure out. The other thing was that their case has a documented connection with the Pope, so it takes it all the way to the top.

What Father Murphy did was horrible, and it was the act of a compulsive predator and we can all be horrified by that man’s sickness, but the real institutional crime is the cover up. When you realize that goes all the way to the top and that it was not just an anomaly, but it was part of what was done, that was a motivation for doing it. I wanted to say, “This is the way the institution works, and this is how they abuse their power.” What made me want to do the film is that it wasn’t just a victim story. These guys are heroes. They really did fight back. They were the weakest imaginable characters, in the sense that they had no voice, but they fought back. That makes them heroes to me.

When you take on a subject of this magnitude, do you have a structure set up to follow, or do you just follow where the story goes?

GIBNEY: That was the big problem. We knew that we wanted to focus on Milwaukee. The reason I like the story is because, if you follow the Milwaukee story, it takes you to the Pope. So, we were going to do the Milwaukee story, and really do it with some depth and detail. But, the problem we always had in the cutting room was finding that right balance and making sure the narrative moves organically, out of that and to the bigger story, and that the two end up reinforcing each other. In that way, we found things that were unexpected surprises that helped us, like finding that protest about the deaf school in Verona, Italy. We didn’t know about that, when we started.

For some reason, maybe because I have an Irish background, I was interested in going to Ireland because a lot of stuff is happening there. And then, we wanted to give a sense of how the same patterns were there, as were in Milwaukee, and also in Italy. As we got into it, in the cutting process, we got to a place where every element was reinforcing every other element, which is the way it’s got to be. But, the hardest part of doing the film was in the cutting room, balancing that panoramic look at the Pope with the Milwaukee story.

The thing that made me want to do it was that we had those connections. We had the letter that Murphy wrote to Ratzinger, and we had the letters that Terry wrote to Sodano, so there were organic connections that we could play on. Honestly, when you’re doing a story like this, it’s not unlike either a non-fiction book or a fiction movie. You want to have characters and you want those characters to have growth and move in the narrative in ways that are compelling. For example, finding Archbishop Weakland from Milwaukee was so important, and it took us a long time to get him to agree to speak, but what was so great about him was that he had met with Terry. He was the Archbishop of Milwaukee, but he also knew Ratzinger. He was a personal connection. And to hear him talk about meeting Ratzinger, suddenly it makes it personal. It’s not just Figure A and Figure B, and it’s not part of some pie chart.

As a filmmaker, were you worried that you wouldn’t be able to convince Weakland to speak to you?

GIBNEY: Yeah, I worry about that stuff, all the time. It took us a long time to persuade Weakland to talk, and we were in the middle of the editing process when he finally did. I didn’t know I would be able to convince him, but I hoped I would. You just have to go forward and do the best you can, but it keeps me up at night. You have to be confident, one way or another, you’ll find a way to make it work, but you know that it’s super important to get people to talk because that’s what makes it personal and that’s what makes it real.

Was there anything that most surprised you, when you were interviewing these deaf men?

GIBNEY: I was struck by the expressiveness of their language and the way that they visually expressed the powerful unleashing of their emotions, in terms of getting it out. That really impressed me. They, themselves, had to go through a process where, for a long time, just talking about this stuff felt shameful, particularly for Terry. Arthur, Gary and Bob, when he was alive, had dealt with it much earlier, but it took Terry a long time to talk about his abuse, openly. But, once they did, then there was a sense that actually talking that out gave them tremendous strength. That was the interesting part, to me. It was a combination of vulnerability because it’s still very painful for them to talk about, but at the same time, that pain was leading them to some kind of greater strength.

What led you to have actors like Ethan Hawke, Chris Cooper, Jamey Sheridan and John Slattery provide voices for the deaf men?

GIBNEY: There was a big debate in the cutting room about whether or not we should use subtitles, rather than have voice-over. We decided, pretty early on, that we would go with the voices for a couple of reasons. One reason was technical. You cut away from these guys a lot, and somebody else will pick up the narrative. If you’ve got subtitles and the sound is silent, how do you convey that? It becomes technical and complicated. Also, we felt that we wanted people to look at their faces and hands, instead of looking at subtitles. It would be more visceral and emotion, if we had somebody that was talking. But, it was weird for the deaf guys. They were always surprised that we spent so much time miking them. They were like, “Why are you miking us? We’re deaf.” But, the sounds of them struggling to speak, we kept in rather hot. In terms of the actors, I wanted good actors and I wanted actors that would inhabit their characters, and not just read what they had to say. I didn’t want a flat translator. I wanted you to feel their characters.

Typically, when children are sexually abused, everyone would expect the guilty party to be punished, but because the Catholic Church is responsible, they’re protected. Did the extent of the cover-up and the way it’s been covered up for so long surprise you?

GIBNEY: It did, honestly. When I went into this, I didn’t really realize what a massive cover-up this has been, and still continues to be. It seems like it’s hard-wired. This kind of attitude is not unique to the Catholic Church. But, what’s surprising is that an organization that’s so dedicated, on its face, to charity and love, devotes so much of its time and energy to covering up the predators within the organization and not protecting the victims, which is really the horrifying part. So, I was shocked. That whole [Marcial Maciel Degollado] case was fascinating to follow ‘cause that’s so much about power and money and the lies that people tell themselves, in order to imagine that they’re doing the right thing instead of the wrong thing. That’s the really horrible part. Because you think you’re good, you think that you can’t do bad, and you begin to develop a rationalization.

When you look at what happened recently, it’s not that I don’t want to throw the institution of the Catholic Church under the bus, because I do, but the Governor of Pennsylvania is suing the NCAA to roll back the punishment of Penn State because he says it’s costing too much money and the football program is such an economic generator. What kind of moral message does that send? It’s not about the victims of the crime, it’s about the case. In many ways, that’s what’s happened with the Church, too. It’s not about the victims. It’s about the Church. The Church must be all-powerful. You discover these horrors within institutions because predators find ways of hiding in plain sight. But, in the case of the Catholic Church, it’s hard to understand how they so willfully sacrifice the children.

The funny thing about being Catholic, and I was raised Catholic, is that you identify with the Church, just as part of your character. Nevermind what you believe, it’s just who you are. So, to reject the institution, in some way, is almost to reject who you are. You resist rejecting the institution, or things that the institution does, because the Church puts you in that position. It’s like the woman in that video, when they go to confront Murphy. She’s shaking her finger at Bob, saying, “You are a Catholic. Don’t forget that!” It’s like you should take one for the team because the team is more important. It’s a horrifying thing, if you think about it, because that’s supposed to accuse everything. It’s like, “Yes, there’s a lot of shitty stuff that we do. Yes, we haven’t protected the children. Yes, we’ve allowed them to be raped. But, don’t forget the most important thing, which is protecting the institution.” What type of institution would want to be protected, if it was doing stuff like that? That’s the question they never seem to ask.

Do you think there’s anything that could be done to ever change this? What do you think would have to happen to get this kind of cover-up to stop?

GIBNEY: I think it has to happen from the top and the bottom. All of us have to say, “Enough!,” and stop putting the money in the collection plate, every Sunday. And we also have to demand that our leaders not treat the Pope like a Head of State. We also have to demand that they disgorge their documents by prosecuting these crimes effectively. But, for the Church to change from the inside out, it means that they have to give up this whole system of secrecy, which seems to be so much a part of the system. I can think of ways that they can show us that they’re serious about it, but it seems unlikely, at the moment, because there’s not enough pressure on them. The idea of a Pope coming out and saying, “All right, we’ve made horrible mistakes and our institution, itself, is to blame. So, as a result, we’re going to disgorge all of the documents relating to sexual abuse, so everybody can see what went on.” You can’t really imagine that happening, but if it did, it would give me confidence. I would think seriously about a Church that would do that. Then, they would be not only talking the talk, but they’d be walking the walk. But for them, it’s a walk off the gang plank, so it’s hard to imagine them doing it.

Obviously, there are priests and individuals within the Catholic Church who really do help people. Do you think that it’s much more difficult for people to trust any priests anymore?

GIBNEY: It is, and that’s a shame. The Catholic Church, in terms of its school and in terms of its work with the poor, is doing good work. Look at how much good work these nuns are doing and how much trouble the Pope is giving them. It’s hard. For so long, the Church has been using those very good works as a way of excusing the cover-up, but we can’t allow that anymore. So, if the priest calls for us to put money in the collection plate every Sunday, we have to say, “No, but we’ll send it to the school. Show us how we can support the school directly without supporting your cover-up of predator priests.” Right now, it seems like the institution has been corrupted by this need to cover up for these crimes. That’s where it becomes tricky. But, you can’t expect the institution to learn, if it doesn’t accept any sense of justice.

Do you know what subject you’ll be focusing on next?

GIBNEY: I seem to be drawn to the subject of the abuse of power, and there are a number of things in that area that I’m digging into. I have a film about Wikileaks (called We Steal Secrets: The Story of Wikileaks), which looks at that issue from a whole bunch of different perspectives. I think everybody is going to be angry at that one. It’s a really interesting story, with a lot of wild characters. It’s a lot about secrets, what secrets mean, how secrets corrupt us, and how they’re sometimes necessary, but once you begin to believe your own goodness, then you think that all the secrets that you keep are good and all the secrets that everyone else keeps are bad, because they’re bad and your good.

Do you have a goal or plan for your production company, Jigsaw Productions, and the type of work you want to do?

GIBNEY: We’re feeling it out, as we go. I’d like to think that there is a variety of things that we could do, that would be fun. I’ve started to do more stuff on sports and more stuff on music. We’re starting to get into fiction. Maybe someday we’ll even do a comedy. Wouldn’t that be a break? I don’t know what kind of comedy that would be, but it would probably be a pretty dark comedy. That would be fun to think about. I guess what we do evolves organically.

Mea Maxima Culpa debuts on HBO on February 4th, and then replays on February 7th, 9th, 15th, 19th and 24th.