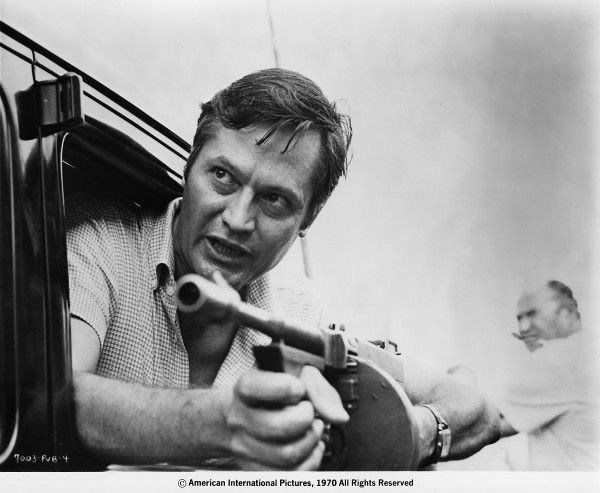

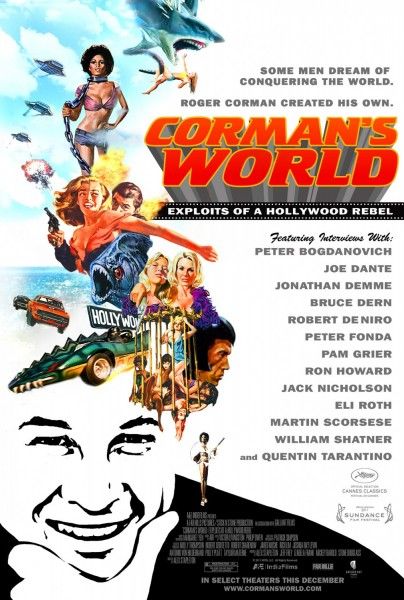

Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel is an entertaining tribute to independent filmmaker Roger Corman that shows why Hollywood and audiences alike owe him a debt of gratitude. Director Alex Stapleton provides a thoughtful look at his influential career by weaving archival footage from his early days of genre-defining classics such as the original Little Shop of Horrors, House of Usher, and The Wild Angels with interviews with producers, directors and actors who started out with him like Martin Scorsese, Ron Howard, Jack Nicholson and William Shatner and video of Corman and his wife Julie on location today as they continue to produce and distribute profitable low budget films outside the studio system.

We sat down with Stapleton at a roundtable interview to talk about her feature directorial debut and the challenge of culling through hours of interviews to produce a fascinating film. She told us what inspired her to make a documentary about Corman, why this film and its message to filmmakers is so timely, and how she was moved by Jack Nicholson’s heartfelt tribute to the man who helped launch his career. Stapleton revealed why she believes Corman’s lasting legacy is not only as one of the true greats of indie cinema, but also as a generous human being who encouraged and inspired other artists and gave them a chance. Stapleton also discussed her upcoming projects: a mini-series on the history of street art and graffiti and a Corman-inspired sci-fi feature about intergalactic love.

What inspired you to make a documentary about Roger Corman?

ALEX STAPLETON: The reason I picked Roger was obviously I’m a big genre fan. I’m a big science fiction nerd and horror film nerd. I’m obsessed with Pam Grier. I wanted to be her for all of my teenage years. Because I didn’t go to film school, I had a collection of books that were inspiring or taught me how to make movies, shorts with my friends back in Brooklyn, and one of those books was How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime which is Roger’s autobiography. After reading that, I realized that oh my God, this guy is behind all my favorite Pam Grier movies. Oh my God, he made the Vincent Price Poe films that ran on television when I was little. He did Grand Theft Auto. He made Death Race 2000. And then, you’re reading these excerpts from some of his protégés, and I realized wow, he also created and launched the careers of all of my film gods. It was insane that no one had told his story. No one had done a documentary in present day. So that’s where the inspiration came from.

How did you first approach him about the project?

STAPLETON: I got it in my head that I wanted to do a documentary about him. There hadn’t been one done since the late 70s. I was living in Brooklyn, had no connection to Roger Corman, to no one in this movie. I didn’t go to film school. I’m like the person who should have never made this film. But I just decided to put one foot in front of the other. I was writing film articles for magazines at the time. I convinced an editor from one of the magazines that I was working for to give me a shot to do a piece on Roger. This was an excuse to go meet him. They flew me to L.A. I sat down with him and immediately afterwards I said “What do you think about me doing a documentary about your life?” He said “Very well.” And, it was as easy as that. He said “Come to my office and we’ll talk about it more.” I pitched him my take on what I wanted to highlight and I think he was into it and here we are.

After you got Roger on board, how did you go about expanding it from there?

STAPLETON: It took a look bit of time for me to find my footing. For two years I was financing this movie by opening a lot of credit cards and I had completely depleted my savings. And then, I realized wow, I don’t think I can do this on my own. I was really lucky to hook up with a production company here in Los Angeles and to get real financing. At that point, Polly Platt came on board the movie and everything just started to fall into place. With real money and a real crew, I was able to properly go after people and conduct interviews.

How much had you shot prior to that?

STAPLETON: I shot a lot of stuff that no one will ever see. That was my student work. What also happened was there was a big jump in technology. When I started, the project was shot on…it was DV. And then, I changed cameras. It was like mini-DV tapes that I have of me and Roger, of me following him around, and no one’s going to look at those.

What about as DVD bonuses?

STAPLETON: I don’t know. Maybe when I’m 70 and I can have a career and go “Oh yeah, that was when…,” but not now.

How did it feel to make Jack Nicholson cry?

STAPLETON: Wow! I had nothing to do with him crying. I was just there. I was at the right place at the right time. That was an incredible day. It took me two years from the first request that went out until I was sitting down in the room with him. It was a Holy Grail interview from day one. As soon as I met him, he said “You know I’ve only gone on camera one other time and that was for Stanley Kubrick, and now I’m doing it for Roger and that’s it.” That was an intimidating thing. I felt like I had a lot of pressure on my shoulders to pull off a good interview. Originally, I only had 20-30 minutes with him and that turned into a full blown day. His assistant kept coming down and he’d go “C’mon, we’re going to go,” trying to give him an exit, but he didn’t want to go. He wanted to stay there and really go through this 12-year period of his life that led up to Easy Rider, a period of his life where he was married, he had a child, and no one was giving him any work. There were a handful of guys that were employing him and Roger was the main guy. By the end of the day, we were actually wrapping the interview up. It plays out how you see it in the movie. He’s like “I hope he doesn’t really think this is me just kissing his butt” and then he just broke down. It was shocking and it was very moving. There was a lot of back and forth with him directly to the camera. I think that Roger became the camera to Jack and I was just a medium there capturing it all.

You’ve got a very fair and balanced chronological piece as your final product. How did you cull through that many hours of interviews?

STAPLETON: Patience and time. This movie took me five years to do and we were in post production for three years because of that fact, because this man had made hundreds of movies. I’m pretty particular and specific with wanting to know everything before I make a judgment call of what stays in the movie and what gets dropped, so it took a lot of time. It was very painful to lose movies like Man with the X-Ray Eyes which is one of Roger’s more famous films, but it didn’t really coincide with the story that I was trying to tell. I was trying to pick movies that ran parallel to what Roger was going through in life and what was happening in America. In the 60s, I chose to highlight the movie The Intruder and then to do the follow-up with telling of the stories of The Trip and The Wild Angels, and X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes just didn’t fit into that formula. That was the rationale. That was the reason why things were dropped. It was very painful. I lost interviews. The most painful interview that I dropped from the film that will be in the DVD extras was that of David Crosby, whose father was Floyd Crosby who won the first Academy Award for Cinematography with a movie called Tabu (Tabu: A Story of the South Seas) and also shot High Noon. He was a great genius behind the camera but could not get a job because he was blacklisted by the Hollywood community because he had liberal European friends. Roger Corman was the only man who would hire him, so Floyd Crosby ended up shooting I’d say about 90 per cent of Roger’s films as a director. He shot Teenage Caveman and all these movies and he was a genius and that’s why the movies were put together pretty nicely, even though Roger didn’t really know what he was doing at that time during that time period. David Crosby’s interview was even more emotional than Jack’s. He was in tears. He was like “Because of Roger Corman, my father could put food on the table. My father had confidence. He was a man who fought for this country that was completely shunned by his own people.” There are a lot of those kinds of stories, but once again, it didn’t fit into the 90-minute experience. I’m excited to share them. That’s the beauty of DVDs.

What was Roger like to work with?

STAPLETON: He was very hands off from the get go as soon as I got him to agree to the film. There’s this separation between church and state. I think he thought that I was crazy and that I was some crazy fan that was making something for YouTube that was probably going to be 10 minutes. I kept it to myself whenever I was booking [interviews] even with Jack. I didn’t want Roger to really know. If it got back to him, that was okay, but I remember the first time we screened the movie when we got into Sundance, and I sat down with him. We were in the screening room together and he watched the film for the very first time. He was like “Really!?” because it took me five years to do and he was like “Why are you still on this movie?” He made twelve movies while I made my one. So it didn’t make sense. I don’t think his brain could compute taking that long to make a film. But then, when he watched it, I think it really sunk in.

In the process of doing this documentary, what did you find out about Roger that surprised you?

STAPLETON: I think that’s a two-pronged answer. First of all, on a cinematic [level], the film answer to that is that Roger Corman was creatively responsible for a lot of cinema history. If you take a movie like Easy Rider which everyone counts as the beginning of New Hollywood, that is a big movement. And then, when you really dissect that film and the people that were behind that movie, you realize that it has Roger Corman written all over it. Easy Rider is a hybrid film, taking The Trip and The Wild Angels and making a new explosion. And the people that were making it, guess what, they were all [people who had worked with Roger Corman]. Peter Fonda was just this clean, cookie-cutter kind of a guy. Roger Corman turned him into the motorcycle man with The Wild Angels. Jack Nicholson, all of them, they all had these images that Roger Corman fueled, and Easy Rider, it was a big surprise to understand how much creative influence Roger had. A lot of people dismiss him as just launching famous people’s careers or being a penny pinching producer, but he’s so much more than that. And then, I think that the bigger answer to your question is what Roger has contributed as a human being. By the end of the film, I really wanted to put down movies and stop with the ‘It was so funny because we had no money’ story. I wanted to really get into an emotional place of realizing how special it is to have a human being inspire and encourage artists that “You know what? You write good press releases. I think you can write a good screenplay.” “You did a really good job for me doing those car crashes on second unit. I’m going to give you a chance to direct a feature.” Who does that? And he was a great supporter of the arts. I think giving artists confidence is a priceless gift and something that was very special to learn about him.

Is there anything about this film that you feel is particularly relevant today?

STAPLETON: Absolutely. It’s even more poignant for this film to come out now than when I started in 2006 because of the current state of independent film, because of the current state of the economy and how hard it is for independent artists to get their movies out there. We need to take a step back and realize that what happened in the 1950s, when he started his career, is exactly where we are today. Everything goes in a cycle, and right now, distribution is changing. Audiences might be kind of sick of these giant blockbuster movies with all these special effects where blue people are running around and the hero is some non-human entity. These are all great movies, but I think that there’s definitely room for new voices to come out. There’s a rumbling with young artists and young filmmakers that are dying to get different points of view, different stories, out there. It’s all changing and happening and they’re able to maybe not play their movies in theaters but get them on the internet. This is the new wave, the new world.

What do you think the message of this film is to those filmmakers?

STAPLETON: Get off your butt and go make something. Don’t wait for permission. It’s great if you go to film school. That’s awesome. If you didn’t get the chance to go to film school, that’s okay too. It’s like learn by doing. You’re never going to read enough books. You’re never going to have enough lectures teach you how to make films. Films are a very tangible thing. It’s making something with your hands. I think all of these guys – Roger and the whole cast of this movie – what they did was they were willing to make mistakes. They were willing to make movies that were really bad. But they learned. Francis Ford Coppola didn’t come out of the womb with The Godfather. He had a whole build up until he got to that point. I think it’s okay to fail. That’s how you learn. I think that’s hopefully what people can take away from this movie.

What did you personally take away from the experience of making this?

STAPLETON: It’s similar to what I hope audiences take away from it, which is putting one foot in front of the other and the school of DIY. I think that’s what I’m taking away from this. Now I feel like I’m a graduate of the Roger Corman School of Filmmaking. I went and visited Roger on the set of Dinoshark and that’s in the movie. That’s where I really got a big whopping taste of what it’s like to be on one of his sets. He recruited me. I was recording sound. I was shooting second unit. I have three different roles in the movie. I was shooting visual effects plates and I was conducting my own documentary at the same time. There is this thing about Roger, where I had never directed before but he gave me a chance, and I think that’s the beauty of this guy.

What have you learned and how will you approach getting distribution for your projects now?

STAPLETON: I think being really open to this new world of online and what it means to be online. Also, understanding that maybe it’s time to let go of the 90-minute experience and realize that all of the content that comes on top of the 90-minute film experience, [that] there’s a lot of that, especially with documentaries. There’s all of the DVD extra material and all these other pieces of information that don’t fit into a 90-minute experience, but it’s still content and people still want to see it. It’s being open to [the fact that] the business is changing and being open to how you can make money to afford you to stay in business to keep making new things. I think you just have to have an open mind and be really smart about stuff and not be so locked into the conventional way of how the process used to go.

What do you have coming up next?

STAPLETON: I have two things on the documentary side of my brain. I did another documentary this year on street art and graffiti (Outside In: The Story of Art in the Streets). I documented the MOCA show, the Art in the Streets exhibit, that was there earlier this year, and now I’m working on developing that into a mini-series which will be kind of a Ken Burns look at the history of street art and graffiti for a cable network. I’m really excited about that. On the narrative feature side of things, in 2012, I’ll be doing a science fiction intergalactic love story that is an ode to my love of Roger and all things Corman creatively, and that will be a low budget awesome feature.

Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel opens in theaters on December 16th.