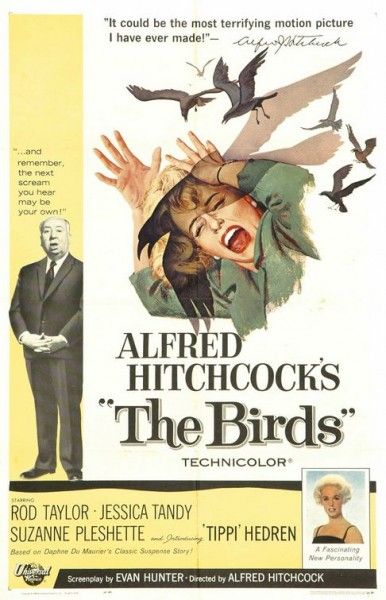

This is a nightmare. I know that sounds hyperbolic and is reason enough to wish harm upon my bloodline, but really, this is one of those moments where you feel like you’re doing a huge disservice right off the bat. If I’m being honest, I would tell you to just start with Psycho and then go on from there until you’ve seen everything, short of some of his shorts and those propaganda movies, that Alfred Hitchcock has directed. Even those silent movies, like The Lodger or The Farmer’s Wife, should be seen at least once for context to the majestic flourishes he would deploy in Marnie, Strangers on a Train, Frenzy, and The Birds, to name just a few.

These are the words of an obsessive, mind you. For most people, the name Hitchcock is synonymous with tight thrills, but that’s not what I think about when I think about Hitchcock. It’s the strange habits, ticks, and ways of being that his characters seem doused in; his is a cinema for, and about, obsessive people. As brilliant a thriller as Psycho is, its most exhilarating moments are those where we can see the psychological creature lurking behind Norman Bates clawing desperately against the wall even as he tries to act sociable. That check-in scene, when he rents a room to, feels as iconic as the shower sequence or the climactic reveal of Miss Bates in her chair. And its this anxious, complicated attitude toward character, and the grand psychological symbolism that color his tales of murder and malevolence, that make his films so undeniably intoxicating, provocative, and wildly unpredictable.

That they were also high-grade entertainments is just as impressive, each one brightly paced and uniquely told, both visually and on paper. Even something as convoluted as Family Plot comes with its own distinct visual flavors in color, composition, and movement – Bruce Dern’s sky-blue jacket and pipe combination is particularly memorable. It’s also, like so many Hitchcock movies, a film that has death on its mind. Perhaps the most wildly fascinating elements of Hitchcock’s best work is the respect he shows for death, even when the demise comes with a certain comical twist. He made death feel calculated yet strange and unpredictable, viscerally physical and explosive in its impact on one’s philosophical and psychological make-up.

His films similarly felt technically assured and yet demonically impulsive; a madhouse run by the inmates, but designed and built under the eye of Frank Lloyd Wright. As methodical as his plots could be, they never felt like a plodding ordeal of necessary plot turns and exposition. On the contrary, they continue to feel galvanic in their pacing, and when he did want to put the screws to you, he was, indeed, a master of drawing out tension for just the right amount of time before it felt over-directed. And this is as true of early masterworks like Young & Innocent or Foreign Correspondent as it is of later, towering works like The Birds or Marnie. So though there’s no excusing the obnoxiousness of saying something like it’s a nightmare to pick a favorite Hitchcock, it remains a reality for a very silly person like myself.

But I sucked it up and did it anyway. Please know already that a part of me agrees with every single comment that says “No [unlisted Hitchcock movie]? Fuck this!”

'Psycho'

There’s no getting around this one. For those who have yet to see Hitchcock’s landmark thriller, in which Anthony Perkins’ Norman Bates attempts to cover up a history of brutal murder in his family home and business, you might be surprised by the structure of the film. The shower sequence is still a kicker, low on blood but high on impact as Hitchcock highlights the physical oomph that goes into each of the lacerations and stabs, but that’s just one sequence in a 105-minute work of art. There’s a certain intricacy to the story, which goes from an affair to a robbery to a chase out of town to a murder and then, finally, to an investigation. Hitchcock’s dense yet seemingly effortless compositions, matched by Joseph Stefano’s script and the menacing, ingenious score by the great Bernard Herrmann, bring out the day-to-day action and atmosphere of each setting and also come to highlight the tension and panic of the film.

In a plethora of sequences here, such as when Janet Leigh’s Miriam Crane locks eyes with her boss in a busy crosswalk, the director unleashes a torrent of moral anxiety, reflected in an everyday fear such as getting caught doing something wrong by your boss. Before we even meet Norman Bates and his mother, the sense of unbearable repression being dismantled is viscerally felt. By the end, as Norman sits there with that blanket, the panic hasn’t subsided, the monster is still alive, and one feels as if we’ve witnessed as much an expressive look at guilt and everyday wrongdoing as we have a ferocious vision of madness released from the calm of societal pleasantries. It’s at once the most controversial film the director ever made and the perfect entry point for a director, who would never stop scratching at the artifice of society to see the perversion and moral rot underneath.

'Marnie'

Whereas Psycho is the fan favorite, along with North by Northwest, Marnie is the oft-ignored yet crucial late work that fully unveils the dark impulses and brave reflection of the filmmaker. Though he would go onto make Topaz, Torn Curtain, and Family Plot, Marnie is regularly considered Hitchcock’s last masterwork and though there’s plenty to gain from seeing the trio of films that followed, it’s hard to argue against that summation. Centered on the titular kleptomaniac, played by The Birds star and Hitchcock muse Tippi Hedren, the film is a kind of melodrama that follows Marnie’s indefinable “romance” with Mark Rutland (Sean Connery), one that leads to a marriage but comes to look a lot like a series of sociological and psychological trials and tests performed on the habitual thief.

The film is a thinly veiled consideration of Hitchcock’s working relationship with his own actresses, with Hedren as well as Vera Miles, Janet Leigh, etc., and of his work on the whole. Like the director prodding at his performers to get them to do what he has envisioned, Rutland puts Hedren’s character through a myriad of tests to get her reaction, to see how the scenarios, discussions, and simple acts will effect her both physically and emotionally. It’s not pretty, and it’s not every filmmaker that can look at this art form with equal parts passion and ruefulness. His close-ups on Hedren here are some of the most effective and evocative of his career, and Connery gives one of his best performances to date as the curious, sadistic Rutland. Even as the intricacies of the plot are laid out elegantly, one can sense that Hitchcock saw the film as a confessional work that stretches beyond its enveloping story, an admission of strange, uncouth behavior excused in the name of great art and, of course, money.

'Shadow of a Doubt'

This is where Hitchcock first became Hitchcock, at least for me, and I’m to believe that this is a somewhat common opinion. Young & Innocent and Foreign Correspondent were the most percussively edited, enthralling films of Hitchcock’s career up until here, but Shadow of a Doubt is a tremendous oddity on any scale, and a triumphant moment of stylistic coalescence for the director. The question posed is simple: Is Uncle Charlie, as played by a particularly smiley Joseph Cotten, a decent man or a killer of women? As told through the eyes of his beloved, much-dotted-upon niece, Charlotte (Teresa Wright), who is often called simply Charlie, it’s a witch-hunt that becomes something a bit more disconcerting.

There’s a distinct America-ness to this film, what with those riotous, extended talks with Hume Cronyn’s Herbie and those big family dinners. The family is painted as fixtures of the community at large, and the entrance of Uncle Charlie sets everything off its axis. He charms many but not all, and the aftermath of his arrival spins out into one of the most sensationally entertaining and wildly menacing films that Hitchcock ever produced. The subtext here is teeming, reflecting everything from sexual identity to political affiliation to religious devotion; there are also all those hard-to-miss incest insinuations. Shadow of a Doubt is also, for me, the story of a shocking arrival, a pointed attack on stability, which would soon become the director’s unmistakable trademark.

'Vertigo'

Considering the amount of material that has been written on Hitchcock, there doesn’t seem to be much new under the sun to talk about with any of his films. This is particularly true of Vertigo, a work that has inspired critical obsession that is simply unparalleled in the annals of cinema. Books have been written and published; articles that would take up most of the room in a New Yorker issue have been penned several times over by some of the smartest critics to ever sit in a movie theater. Before I saw the film for the first time, in my late high school days, I had not one but three separate teachers offer me their personal copy of the film. They could have, conceivably, been fired for such things, as Vertigo is indeed one of Hitchcock’s most unsettling yarns, a ruinous, lascivious death dance between policeman Jimmy Stewart and pretender Kim Novak.

Like Fonda in The Wrong Man, it’s exactly the fact that Stewart is such a heroic fixture, the resilient cowboy or The Man of the Law, that makes the whole experience so beguiling, as if to convey some sense of displacement. The director was indeed looking to open the door behind the lock behind the wall behind the false bookshelf, the dark place we don’t talk about without being driven to. That Vertigo is also such a visual knockout, a florid arrangement of colors painting a cutting psychosexual melodrama and an enraged act of self-excoriation for a man who often needed to recreate women under his exact specifications for his work. As consistently alluring as it is unbelievable and prickly, Vertigo is one of those films that is never quite complete in your head, always suggesting new ideas on subsequent watches that add a previously unknown depth to this preposterous story of doppelgangers and murderers. Nevertheless, the film makes you bewitched by these characters, and the wreckage left by Stewart’s delirious obsessive is unlike almost anything else in the movies.

'The Wrong Man'

Half of the time, when I’m asked what my personal favorite Hitchcock is, my answer is The Birds. The other half of the time, it’s The Wrong Man. I can’t precisely tell you how I come to pick one or the other, but it’s been these two since my college days, when my heart belonged solely to Strangers on a Train and its teeming psychological underbelly. There’s a similar anxiousness that underlines every step across a wet city street, every glance at a stranger walking closer on the sidewalk in The Wrong Man, which is deceptively one of the master’s most straightforward narratives but invokes an unshakeable feeling of mortal guilt and intimate, haunting self-knowledge.

This would be the only time that Henry Fonda would show up in a Hitchcock film, and boy, they made the best of the singular collaboration. The title says it all: Fonda’s Manny Balestrero, a loving husband and trained musician, is brought in by the police and is suspected of committing a heinous murder, despite the fact that he’s innocent. The movie makes great use of a supporting cast that includes Vera Miles as his wife and Harold J. Stone and Charles Cooper as the detectives on his case, but the film is really about Manny and what he knows. With the possible exceptions of John Ford and Otto Preminger, nobody used Fonda with such confidence as Hitchcock did, at once reinforcing and picking at the good-guy persona that Fonda was known for.

The filmmaker focuses on the actor's eyes, darting around in panic or fixed in contemplation and resignation. In these moments, there’s an unmistakable sense that though he may be innocent of the crime he’s been charged with, there’s something that he won’t talk about that stirs up tremendous guilt and worry in him. Is the price of living that one must feel guilt over how they survive? Does Manny accept the punishment that he goes through as payback for his secret? Matters of religion, justice, self-awareness, and, yes, shame are at the heart of The Wrong Man, but beat-for-beat, this masterpiece feels like an unpolished yet visually gorgeous depiction of being not only a human, but also an American.