Thirty years ago today, Steven Spielberg, Don Bluth, and David Kirschner brought the animated kids movie classic An American Tail to cinema screens. It introduced the Mousekewitz family and their cute, curious, and adventurous son Fievel, who would go on to become an international icon along with his signature, over-sized, floppy hat. And yet, as classic an animated family-friendly movie as this is, you don't have to scratch far beneath the surface to uncover the rich tapestry that conveys a strong moral message.

It was the first movie I ever saw in the theater. Thirty years later, the lessons I learned through watching the heartbreak and joy of the Mousekewitz family feel more important and relevant than ever. What I once regarded as a darkly serious and sometimes silly tale about a young mouse separated from his family on the streets of New York City has matured into a harrowing allegory for our world’s enduring evils: racism, the vilification of “the other”, and the breaking of the Golden Rule.

We could all do with a revisit to An American Tail. To be quite certain, an animated movie about cartoon mice is not going to solve the world’s problems, but the film’s very obvious moral message appears to be one that’s been forgotten by many of us who are old enough to have seen it in theaters, or perhaps never learned by entire generations of younger moviegoers. An American Tail stands the test of time, in part because its characters are so endearing, its message is so easily grasped, and, let’s face it, the soundtrack is just classic. But it also works in the modern era because the evils it rallies against are still very much a part of our culture, just as they were 30 years ago, and just as they were in late 19th century Russia where the story of An American Tail begins.

Anti-Semitism in 19th Century Russia

In 1885 in the village of Shostka, Russia, stands the house of the Moskowitz family; at its base lives the Mousekewitz family, composed of Mama and Papa, Fievel, Tanya and an unnamed baby, in their cozy abode. To the three-year-old me, neither the village’s name nor the surname of either family meant anything, nor did Papa wishing his family “Happy Hanukkah!” twice; apparently this also meant little to Siskel and Ebert at the time. To the 33-year-old me, however, these simple clues tell me everything I need to know to get this story started.

Shostka is an actual village that was established by Ukrainian Cossacks who were based there and, in the late 19th century, existed in an area known as the Pale of Settlement. This area allowed permanent residency by Jews—the region outside the Pale’s borders generally prohibited it except in special cases—but the Jewish families who lived there experienced poverty and conscription into the Tsar’s army. The Pale was also the site of anti-Semitic pogroms, or violent riots directed at a certain demographic, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

That’s a lot of information to bake into the opening of a kids’ cartoon movie, but even those of us who haven’t studied Imperial Russian history can easily understand what happens next. A band of torch-bearing Cossack soldiers on horseback ride through the village, setting it ablaze; a group of mustachioed cats follow in their wake and terrorize the mouse population. This violence results in the destruction of the Mousekewitz’s home and forces them to make the 2,000km trek to Hamburg, Germany with the hope of escaping persecution.

All of this dark material is preceded by a warm, wonderful moment showing the Mousekewitz family celebrating Hanukkah. Papa stresses the importance of their family’s (and their people’s) history and culture with both a retelling of the tale of the Giant Mouse of Minsk and a physical hand-me-down in the form of Fievel’s all-important floppy hat. These lessons, and the promise of greater opportunities awaiting in America, act as bookends before and after the attack; they give the Mousekewitzes hope to preserve their culture while also continuing it by embarking on a grand, promising adventure to the New World.

Immigrant Refugees: Flight and Plight

In Hamburg, the Mousekewitz family members were just a scant few of a long line of immigrants from across Europe who were boarding a steamer bound for America. The gathered travelers—Russian Jews, Irish, and Italian immigrants alike—huddled together in any space they could find in the hold of the ship. The Mouskewitzes played songs from their home country before uniting together with the other passengers to sing “There Are No Cats in America” in which the all-too-familiar tales of atrocities set upon them by cats were told, only to end with the hopeful message of a promising, cat-free America. To put it briefly, they were not alone in their tragedies nor their hopes for a better tomorrow.

From 1880 to 1930, the “Great Wave” of European immigrants flooding into America was estimated at 27 million. This was during the time of increasingly exclusionary and bureaucratic legislation meant to restrict immigration from certain regions (mostly Asia, and specifically China) and generate revenue for each non-American citizen seeking to move into the country. A modern crisis of emigration and refugee flight is currently happening in Europe, though the U.S. tends to be less warm and receptive than that of our friends and allies across the Atlantic. Thousands have already died in transit while trying to cross the Mediterranean, a modern-day tragedy morbidly mirrored in An American Tail when a deadly storm thrashes the steamer ship and separates Fievel from his family; Papa and Mama are forced to give him up for dead, but of course that’s just where the tiny mouse’s American tale begins.

Arrival in America

An American Tail actually takes the time to show the Mousekewitzes going through legal immigration procedures, presumably at Ellis Island, which was the nation’s busiest gateway for immigrants for the first half of the 20th century. Tanya’s name was changed against her wishes, perpetuating a myth that this was commonplace but also setting up a plot point for later in the film. Regardless, this was a relatively insignificant slight for the family after the loss of their only son.

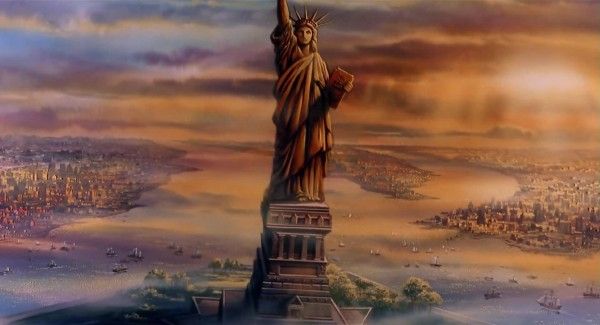

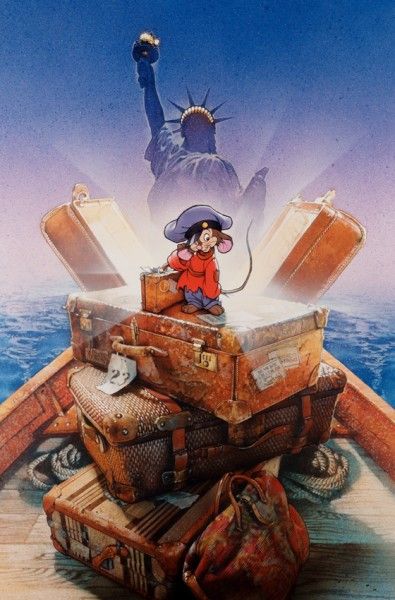

Except Fievel is alive, if not exactly well. He washes ashore in New York City’s harbor, floating in a bottle past the Statue of Liberty that’s still under construction. It’s here that Fievel makes acquaintances with the first of many fellow immigrants: a French pigeon named Henri (voiced by Christopher Plummer) who was working diligently on finishing the statue that would welcome immigrants the world over with its inscribed message of hope. This is but the first positive reinforcement of the message of America’s open arms to the people of the world.

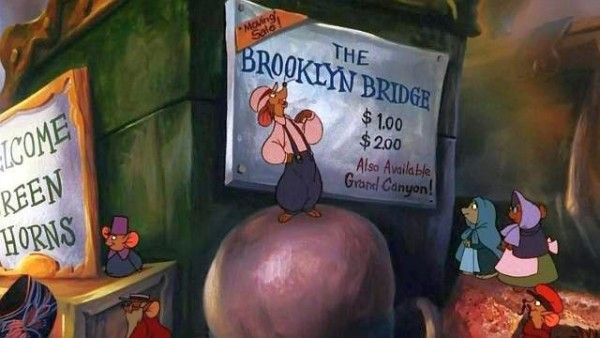

But Fievel’s travels through the hard-luck streets of New York City were not what he had been promised. In a marketplace in the slums, hucksters and conmen try to sell the Brooklyn Bridge or a ticket to Chicago “used only once” along with other scams. It’s here that Fievel meets the slick and charismatic Warren T. Rat. Unbeknownst to Fievel, this fellow is actually a cat in disguise who’s been charging the mice a protection fee but providing no actual protection from the cat gang, the Mott Street Maulers. He quickly befriends Fievel before selling him to a sweatshop. The ties between immigration and sweatshops and the multi-billion-dollar garment industry still exist today, even after the tragic events of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Still a kids movie, An American Tail doesn’t linger here, but rather uses this scene to plant a flag along the path of immigration and assimilation in America. It’s also where Fievel meets the very helpful Tony Toponi.

What follows is a whirlwind of other immigrants who cross Fievel’s path. Some, like Tony, are street-smart but struggling to get along, while others, like the principled Irish mouse Bridget and the uber-wealthy Gussie Mausheimer, are well-to-do and focused on rallying their fellow mice to their cause. During one such rally, Fievel learns that the promise of a cat-free America was a false one; cats savage the meeting in a public market and destroy everything they can get their claws on. It’s after this event, and yet another failed attempt to locate Fievel’s parents (no thanks to the drunk but well-meaning politician Honest John), that the mice decide to do something about the cats once and for all.

The Mouse of Minsk

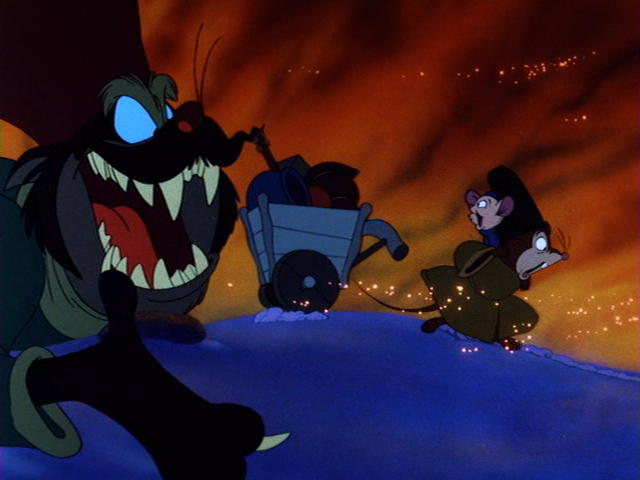

Very early in the film, Papa Mousekewitz tells Fievel and Tanya the legend of the Giant Mouse of Minsk. It’s this cultural touchstone that ultimately saves the mice of New York City thanks to Fievel’s recollection of the story. The legendary mouse, “as tall as a tree with a mile-long tail”, was seen on screen in two iterations: the cutesy shadow-puppet formed by Papa Mousekewitz, and the terrifying, nightmare-inducing, monstrous metal creation made by the combined efforts of the immigrant mice.

This climactic scene, clearly influenced by the Jewish legend of the golem, works on a number of levels: the mice are only able to defeat the cats through their combined efforts and unified purpose, the cats are summarily beaten by an out-sized embodiment of the very victims they terrorized, and they’re run out of their own country on a steamer ship bound for China while the victorious immigrants stake claims in their new home. It’s fantastic. And the spirit of the whole thing is summed up by Gussie’s rallying cry of “E Pluribus Unum”, which just so happens to be the motto of the U.S.: “Out of many, one."

But while the problem of the Mott Street Maulers has been resolved, there’s still the issue of the missing Fievel and his necessary reunion with his family. It’s definitely worth noting that everything in Fievel’s travels to this point—his trustworthy and naïve nature, his friendship with fellow immigrants, and his ability to turn foe into friend over shared interests with the lovable Tiger (Dom DeLuise)—ultimately lead to him meeting up with his family once again in a heart-warming scene that makes all of their hardships worthwhile. The clincher is Fievel and friends’ flight past the newly completed Statue of Liberty (which literally winks at them) as they soar toward the horizon for the waiting promise of an unexplored frontier.

Taking An American Tail as it stands, without worrying about the film’s sequels and animated series that inevitably followed its success, it’s plain to see that its messages are still very relevant today. Did the filmmakers think that their little animated movie would solve the world's problems? Probably not. But they also probably didn't envision the reality of supposedly intelligent adults needing a kids movie to refresh them on the evils of racism and bigotry, or the virtues of inclusion, diversity, and plain old decency.

Clearly, we're all in need of a refresher. But there's always hope. I mean, if cats, and mice, and birds can all get along together despite their biological conflicts, there should be no issues for fellow humans, right?