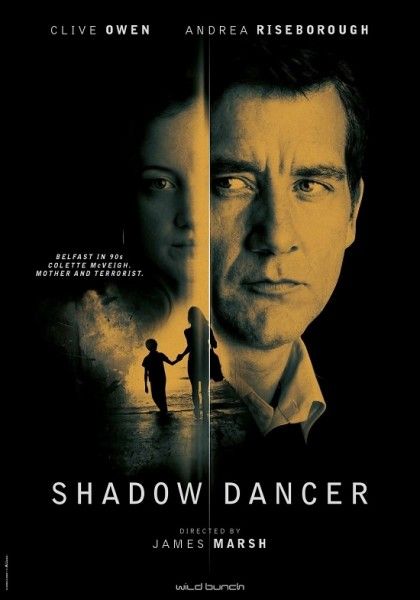

Andrea Riseborough delivers a compelling performance as Collette McVeigh, a character who risks everything in Shadow Land, Academy Award-winning director James Marsh’s taut, thought-provoking adaptation of the Tom Bradley conspiracy thriller about an IRA member turned MI5 spy in 1990s Belfast. A single mother living with her mother (Brid Brennan) and hardliner IRA brothers (Aidan Gillen, Domhnall Gleeson), Collette is arrested for her part in an aborted IRA bomb plot in London. An MI5 officer (Clive Owen) offers her a choice: go to prison and never see her son again or return to Belfast and turn informer against her own family. Opening May 31st, the film also features Gillian Anderson.

At the recent press day, Riseborough talked about her character, what drew her to the complicated role, how her RADA training helped her prepare, what it was like traveling back in time to the 1990s, her personal experiences and memories of the era, her close collaboration with Marsh, why the film was shot in Dublin, and how it’s been received by the people of Northern Ireland. She also discussed her portrayal of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in The Long Walk to Finchley and her upcoming role in Alejandro Iñárritu’s dark comedy, Birdman. Hit the jump to read the full interview.

Question: Collette seemed very complicated, yet distant. Was she a tough character for you to play?

Andrea Riseborough: It’s very difficult to quantify what it’s like to approach a character, especially one that’s gone naught to turf. You understand what I mean? It’s like saying anything in life, “How tough was it?” Part of the reason I enjoy my job is because it’s such a challenge. It was a great challenge. Everything I have ever worked on has been a great challenge, so it doesn’t stand alone in that respect. She’s a very interesting character, because when I came to her, textually at least, her story was more a situation than it was an expression of her inner life. The script was, as any script is, dictating a situation for many parties. It’s attracting an actor of some sort. In that case, it was me. James was attracted as the director. Tom also, when he was writing it, was thinking about getting it funded. He was writing it for so many people, and she spoke an awful lot. The more time that I spent in Belfast, and the more that I built the inner life that Collette has in the film that we see through her eyes, the more I understood a need not to speak, and the more I asked James if he would be comfortable if she were far more economic with her words. And so, we went from somebody who spoke an awful lot in the script, which was something that I was unsure about when James offered me the role, to a character whose most powerful quality is her silence in a time when people were operating purely from fear in a paranoid society and it was so difficult to get through each day. I find it interesting that you say you find it difficult to understand who she was, and I understand why you do. That was one of the things I liked about the story, because I thought it was so wonderful. I was so eager to be part of a story that explored not just an usual generic redemption tale of somebody who fought for a cause and then saw the error of her ways, and therefore we can all identify with her because it’s being human, but that she was true to the courage of her convictions, that she grew up in a place with 85% unemployment where people couldn’t go to the center of the town for fear of being killed, that the film actually gave a voice to a percentage of the world’s population so small that I felt had been so grossly misrepresented.

You’re big on research. Did you read the book prior to making the film?

Riseborough: No. I started to read the book and it’s like so many things now. A lot of films that have been adapted from books stop serving you because they become different. I mean, they are different entities in themselves, but artistically, what you’re trying to achieve with a film is so very different to what you’re trying to achieve with a book, and the way when you write a script is so very different on paper to how it seems on a screen. So I stopped reading it. James did, too. We just felt like it was a completely different story by then.

What draws you to a role like this compared to a character like Vika in Oblivion which is a much larger scale film, with a different type of cast and much more fast-paced action? Is your preparation similar or different for each?

Riseborough: Well I suppose the similarity is that both Vika and Collette, and it’s even strange to talk about them both in the same breath, were blank canvases in the sense that they were there to be discovered because Collette’s situation was there and Vika’s situation was there. And therein lies my job, to come in and pad that out. There was an opportunity to do the groundwork and feel what that might be like. For Vika, it was about spending a lot of time with a NASA astronaut, and it was a whole different kettle of fish, and imagining the solitude of her life and the regime. With Collette, we were representing a time that was very tumultuous and a people who went through something very difficult. And so, it was really important to us that with everything, we served it with a certain amount of authenticity. Everything was as authentic as we could possibly make it moment to moment. Certainly, there wasn’t that same kind of pressure with Vika, except when I’m operating equipment in that scene where they’re actually inside of a spaceship. That was very important, but it was very different.

How did your training at RADA help you prepare? How do you fill in those kinds of spaces when it’s not very talky and there’s an interior life to the piece?

Riseborough: That’s my job. It’s to bring it. Originally, Collette talks an awful lot in Shadow Dancer. She was Chatty Cathy, so we shut her up. And then, her strength was silence. Her greatest power was her silence and that she had a keen sense of self, even if she’d not cultured or cultivated her likes or wants or needs as a human being because she had a greater mission that she was on. The inner life came from all of those things. I discovered that inner life from the outward in from the situation and getting very close to people who were in that situation, who had lived through that. Clive (Owen) and I both trained at RADA, although at a different time. I feel instinctively that drama training is a very personal choice. I think it can give you some wonderful things. It can give you great technique that you can then explore, if you choose to, like weights, voices, rhythms of people outside of yourself. And that doesn’t just extend to film. It extends to theater and all sorts of different mediums. You can really hone your craft. However, I think it’s so personal. For some people, it’s right. And for some people, it’s not. For me, I wouldn’t have wanted to spend three years of my life anywhere else than RADA at that time and with the wonderful people who were in my year, some fantastic actors like Tom Hiddleston, Andrew Birkin, and Ashley Madekwe. We had a fantastic year.

You mentioned speaking to people who had gone through this, but you weren’t part of that generation. What were your personal experiences and memories of this era?

Riseborough: It was very much a part of my childhood, and in Britain, it was on the news every day. It was normally the first or second news story. I thought that I had a much closer relationship to it than I actually did. Once I started to delve deeper, and this was even before I arrived in Belfast, I had started to read more and watch more footage, I realized what had been reported was really the tip of an iceberg, because great political correspondents whose reporting I still trust to this day, who were fine journalists, weren’t allowed to report on informers anyway. There was a huge embargo and it was very tricky. There was a huge amount of censorship, and we were operating under a government which I was born into for the first part of my life. All I knew was that we had a female prime minister. I was so confused when we got a male prime minister. I had no idea of what that might be like because I was born into it, so it was totally normal for me. What I hadn’t realized was the freedom with which Thatcher had [operated]. I really can’t describe it. She was very free with her orders in terms of Northern Ireland, and as you know, she was convicted in her own beliefs and not easily shaken or swayed in any way. There was virtually a permission to shoot policy with a rubber bullet point blank in the head of a child, and of course, none of that was reported every day. Of course, it wasn’t. So huge amounts, it was like an endless chasm. I couldn’t believe the depth of my ignorance having felt very much like a grown-up in it, because constantly we had bombs, and it felt very close and very real. That was all very interesting.

Speaking of female prime ministers, you did a great portrayal of Maggie in The Long Walk to Finchley. Did you ever get to meet her and what was your reaction when she passed?

Riseborough: I didn’t get to meet her. I chose not to pursue meeting her when I was going to play her. That’s because when you meet somebody you’re about to play, sometimes you start to feel an obligation to represent them in a favorable light, and I wanted to represent her in a very honest light within the context of our piece. Our piece was a romp through the imagination of what Maggie’s life could have been. That’s why I loved the piece so much, because I got the chance to explore what she might have been like as a girl, but also with a huge amount of fun. Otherwise, it would have been probably quite a depressing piece. Grantham is many things, but it’s not the most exciting place on the planet. It was interesting to see it from two sides. It was interesting, too, to sit in the room where Thatcher grew up and watch the Catholic school across the road and think and understand why she wanted to get out of there, which is interestingly now a holistic retreat. And then, to be in Belfast and be surrounded by the people who wanted and tried to make sure that she was no longer with us.

The ‘70s, ‘80s and now even the ‘90s seem like such bygone eras given how fast society and technology move nowadays. How did you feel about stepping into that time machine and logistically recreating this era?

Riseborough: It’s interesting when you do something that’s set in relatively recent history, because it almost shakes you up into realizing how long ago it was and how much has changed. If we all think of the ‘90s, it seems so close. And then, to step into a set in 1992, it just seemed like walking into a ‘50s television set. It was a very unusual experience, but it also was a wonderful experience, because James cultivated an environment on set that felt like we could retain that Belfast bubble, and I was the carrier pigeon. I was the only messenger who could go up there and come back down and make these suggestions because I was within the world there. I had found a way into the world, so I could come back and bring any authentic offerings that I had. Even though we were filming in Dublin, which was deeply unhelpful as wonderful a place as Dublin is to film, it’s so wonderful filming in Dublin because the crews are fantastic. People are very, very helpful and very warm and very friendly and hard workers. The difficulty filming there was that geographically, as close as it is politically and socially, it’s light years apart, and I don’t think that’s any new information to anyone. We had to pretend we weren’t in Dublin.

May I ask why you didn’t film it in Belfast?

Riseborough: I think you know the answer.

I thought they were encouraging filming there now.

Riseborough: Certainly, but not films about this particular subject matter. It’s just that people have had their close family members killed. Terrible things have happened to those people. It’s so sensitive, and even in light of recent news, as you’ve seen, there are still many open wounds. If you think about how long ago this all started, which was in the ten hundreds, it takes such a long time to sew up a wound that deep.

What’s been the feedback from people who have lived through that era? Have they watched the film?

Riseborough: James wrote to me as soon as it happened. James and I have a great relationship. We work together really well and we’re often immediately on the same page. It was a lovely, very collaborative, warm feeling working with James, and so we always keep in contact. He had had a screening. I was filming somewhere else. I might have been in Louisiana filming. He had a screening in Northern Ireland, and the response was overwhelmingly heartfelt and warm. It felt in part to him, and when I received his email to me, like they’d felt recognized in a different way. They felt recognized in so many ways and should. I just mean artistically. The film is not sensational, especially in light of everyone banding around the word ‘terrorism’. God only knows what that means, but it seems to mean anyone who’s against the ways of the Western world. So it was very interesting to hear people. It was very rewarding to know that a people who had suffered that 85% unemployment and sadness and inability to feed themselves even feel like something had been said about that part of the struggle.

We had an interesting question at Sundance which was: why was it not about the other side? That question is what it is, but then, if it’s about the other side as well, then that gives each side maybe only an hour each instead of one. You don’t get as in depth with one. What have we learned? We’ve learned half of two things now. And then, you add another couple sides in because there are not just two sides. There are sixteen or twenty or twenty-five. Once you started telling it from every [side], then everything becomes about everything, and then why haven’t we likened it to the war in the former Yugoslavia? The film would become endless, like an endless representation of conflict, rather than just focusing on this one story. None of us had a political affiliation one way or the other. We just felt that it was interesting to explore what it might have been to be a regular family going through something that was incredibly taxing and in a time where it was so paranoid that you really had no idea if another member of your family was even fighting for the same cause. It’s difficult for us even to imagine that kind of paranoia.

What do you have coming up next?

Riseborough: I’ve just finished Birdman in the last couple of days, which is directed by Alejandro Iñárritu, and we’ve had such fun filming that. My character, Laura, is wonderful. She’s a fairly low brow actress. She’s from Los Angeles. She has no filter. She’s incredibly sexual. She just wants to fuck anything that walks, men and women. She operates on a very thin level, but she has a lot of depth. She lives in a cutthroat place. It’s about a lot of characters putting on an adaptation of a Raymond Carver short story, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. So it’s been wonderful because it’s been almost like filming a play in many ways, and we did it in the theater so we just laughed and laughed. It’s been so much fun.