Making the move from directing animation to live-action was the big question facing Andrew Stanton when I visited the set of John Carter in April 2010. Stanton had already delivered two amazing Pixar movies with Finding Nemo and WALL-E, but he headed to Mars with John Carter and Mars was a mix of live-action and CG. Stanton was refreshingly honest about the transition and how the two mediums compare. He also talked about his frustrations with the live-action process, how the film isn't in post-production but "Principal Digital Photography", the process of adapting the book, trying to flesh out the main characters, where they're at with the planned sequels, and more.

Hit the jump to check out the interview. John Carter opens in 3D on March 9th.

Question: It seems like the mini-sandstorm outside has kind of quieted down.

ANDREW STANTON: It's kind of overcast now. We've switched to setting up for dusk.

Isn't that a good thing?

STANTON: No, because you can always change -- You can't add shadows. If you really want to get dimensional lighting, you want nice, hard shadows. Overcast isn't our friend. You can always make the sky a little different or tone it down, but you can't do that much. We wait for bright sunlight. Hard, hot Martian sun.

I think you're the first person we've talked to that's not completely beaten up.

STANTON: Really?

And you seem so energetic. How do you keep that up with everything that's going on?

STANTON: Everyone says that and I think you caught me actually a little less energetic. But I don't know. I just sort of accepted my fate before I went onto this that it was going to be hard as hell. It's sort of like saying, "Okay, we're going to go sail around the world." There's nothing really easy about that and there's something mental about just accepting that up front. I've been through blizzards in the UK and volcanoes delaying staff and cold nights and hot mornings. It's been fine.

How does it compare going from the studio to the outside world where you can't control the elements?

STANTON: Well, again, I knew that was going to be the case and certainly that's the biggest change. But it's not as different as I thought it would be. People think -- and I know they don't really think this, but their unconscious knee-jerk reaction is -- "Oh, you work with computers. Therefore you don't work with people." The truth is that I work with 200 artists every day that are incredibly talented at their jobs and they've been good at it for two decades. I have great DPs, great costumer designers, great set designers, great actors and I've had to speak the language and move lights around, move sets around. All that stuff that you have to do out here. It translates pretty much directly out here. It's just how they do their job is different. But what I have to do in telling them what to do and how the shot should look when it's actually on frame in the camera, is not that different. They're actually quite impressed that I can hold so many elements in my head because it has yet to challenge me to the level of Pixar. There's something about CG animation where nothing comes together for weeks or months. You have to hold all these disparate jigsaw puzzle pieces for such a long time. You're the only one who is hoping and crossing your fingers that this is what the picture will look like when it all comes together. I'm only asked to do that for a couple of hours here or a day. Then I get to see what we've all come up with. They're very impressed with that mental strength or capacity. All the other animation directors are like, "What's it like? What's it like?" and I go, "Guys, you'd be fine." Pixar is like a massive boot camp for that. They're also very shocked that we can picture images in our head before seeing anything. Before we see rehearsal or anything like that. That's all we've ever had the option of doing. We have to come up with it before we make it. I didn't realize that it was such a weird muscle to have. It's been very advantageous on something like this. But I've also been incredibly spoiled. I realize that one of the reasons that it's easy is because I've been given some of the best people in the industry on the crew. I couldn't have a better, more talented and more cooperative cast. They've made what is a very, very hard shoot seem doable and sometimes downright fun. I've lucked out on that and I can't take credit for it other than saying yes to accepting all these people.

What's been a challenge for you, then?

STANTON: It's interesting to see the system and how the live-action system works. It's based on a lot of things that maybe made sense in the day or decades ago or are holdovers from the studio system. It's unionized and there's a lot of rules that don't make a lot of sense logically. Pixar has none of that. I realize that one of the reasons it's Nirvana is that we didn't realize how a movie was made and just used -- god forbid -- logic. We figured that if we made a movie the way it should be made, that was the way they were being made. Our system is very logical and we keep improving upon it. We criticize ourselves and we have post-mortems every movie to improve the system. Out here, nobody questions the system. It's just the way it is with all its faults and everything. We don't have unions. Steve was very smart. He said, "Let's give them why there was unions. Let's give them great healthcare. Let's treat them extra special and there's no reason to have that." There aren't these weird byproduct rules that actually cause problems in one area when they think they're helping another.

We have a very clean system, Pixar. After you've worked in that, it becomes very obvious how things should work and very obvious how things don't work the right way here. I get a little frustrated at the haphazardness of it. The world of moviemaking, since the studio system broke down -- and this is my guess -- lives and breathes off of triage. It lives off disaster planning. People feel comfortable in the disaster. "Oh! I know how to deal with this. This is chaos. Somebody's on fire. Let's run and get an extinguisher." That is not Pixar. Pixar is planning to avoid every disaster possible. It's a very opposite experience to the extreme and that took my awhile to get used to, the embracing of the chaos. There's a certain level of it that I feel is necessary. I feel like a parent having their first kid and I can't wait to have to the second one because I'm going to do the parenting a bit differently. I'm somewhat half observer and half participant in watching how this whole things happens.

This film has an extensive post-production phase --

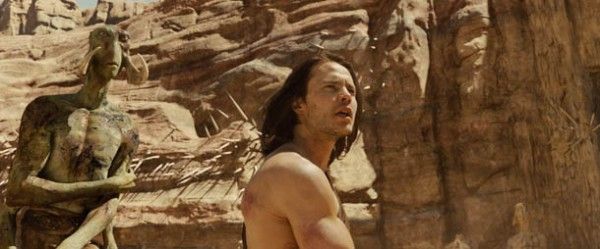

STANTON: I don't call it post. I call it "Principal Digital Photography". Once you look at it like that, you realize, yeah, I'm not done with this shoot at all when I finish in June. Four of my leads are CG and I'd say three or four supporting cast members are CG. Then half the world -- not half literally, but the extension of worlds and the extension of sets. These things that are so massive and fantastical that you can't build them -- have to be done. The movie always was planned to be half CG and half live action. Not in look, but in the attempt to build this vision we had. Hopefully, if we do it right, when it's all done, nothing will look CG and you'll just accept it. That's all I ever wanted. I always came to this just as a fan. I've spent 40 years of my life just wanting to see somebody make this movie and just see it as a fan and only four realizing, "Oh my god! I can maybe be the one to do that." All I ever wanted was to just believe it and see it on the screen. That's really my goal, to not be showy or spectacle for as much as there is, but just believe that I'm really there. Because I've spent a whole lifetime just wanting to go there.

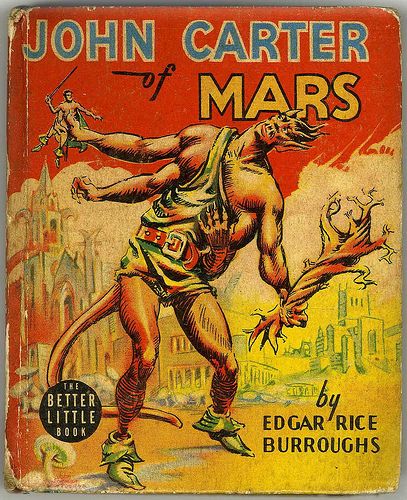

Can you talk about approaching it as a fan and what it meant to be able to bring it to life as a super-fan of the property?

STANTON: Well, I've been a fan of movies longer than anything else. One thing I learned a long time ago is that you can't translate a book literally to the screen. It won't work because it's a different medium. And it would be the same in reverse. There's this naive belief by some people that, if you do exactly what's in the book, it's going to be good. I would say that that's false thinking. I would say that even movies you think are great adaptations of the book, if you were to compare them, you would suddenly realize, "Oh my gosh. They changed a lot."

What would you say that, at the core, was the most important aspect to maintain?

STANTON: Well, the books were serials. The thing that people don't realize is that the books were originally written as serial chapters in magazines. They all had a three act structure in each chapter. You can't make a movie like that. It'll just be this episodic series of train cars going together and it'll annoy people. How can you keep the spirit of what it felt like to be in the book and to be in these scenes and to be with these characters and to make it work in a three act structure for an overall film. That's where I came at it. Believe me, there's a million scenes that I just imagined in my head reading a million times over in the book since I was a kid. Now that I'm older, I still want to see them and I'm trying my hardest to see that they exist in the film, but the thing that has got to work first and foremost is that the story overall works. And that I invest in the character. To be honest, I never actually invested in Carter 100%. He was always a kind of Prince Valiant, did-it-right-from-the-get-go kind of bland, vanilla guy. I think it was his situation that was more fascinating to me. It was a stranger in a strange land, guy thrown out to circumstances. Also, there's the oddity of the time period. I really love that somebody from the Civil War gets thrown into what we would consider the antiquated past of Mars. That's been something that I've really tried to embrace on this and give it its special thumbprint.

Its been such the touchstone for so many things since 1912. It inspired, either directly or indirectly, things like "Flash Gordon", "Star Wars", "Superman" all the way up to "Avatar". If you literally made the book, people would think I was ripping off everyone else and that's the catch-22 about it. So I thought, "What's the spin into it that will make it feel fresh and stand on its own ground?" The approach that I finally decided on was that it should feel like a period film. It should feel like it's historically accurate to everything that really does happen on Mars, as odd as that sounds. It's the same way that I might watch a film about a civilization that I didn't know about in the deep regions of South America or the Middle East of Asia. If it's done in the right way, maybe I'll go, "Wow! Maybe that's how it really is on Mars." I'll sense these layers of history that go behind it and that go unexplained. I've already gotten to see a bit of what it's like to juxtapose New York City in 1888 against suddenly cutting to Mars and cutting to Arizona in the same time period. It really has a nice, period spin on it. Cross my fingers, I hope it'll go in that direction if not nail exactly what I was going for. I think that's what's needed to make it stand out on its own. If you really nail out the bones of it, it's a structure that many films have done.

Burroughs goes into great detail about the setting and the creatures. How loyally did you follow those designs?

STANTON: Well, he's very description, much like Tolkien. Sometimes to a fault. I remember reading "The Lord of the Rings" and getting to a whole chapter about a hill. But it's really helpful for us for our direction and how we want things to look. Again, what I would do is try to follow the basics, but what was really the rule book was, "Do I believe it? Do I believe it really exists?" I don't want anything to look -- for lack of a better term -- fanboy. I don't want it to look like it's something that I've been drawing on my notebook my whole life while ignoring the teacher and now I finally get to put the Arnold Schwarzenegger bicep guy up on the screen. To me, I roll my eyes just at the thought of that. I want to go, "What would nature really create if that was the case with Tharks and beasts with multiple legs? What would the architecture have to be for a world that is so arid and desert?" Always using the framework from the book as a jumping off point, but tweaking it the moment we felt it was fantasy for fantasy's sake. For example, I made the Tharks in the height range that they've been described a little bit lower. In the book, they're been nine and fifteen. I made them between nine and ten. But I made them very thin and very ropey because I looked at all the desert-dwelling tribes that we're aware of -- the aboriginals and the Maasai warriors and the bedouins -- nobody's thick. They're all down to the sinewy muscles and just the essentials. They're the definition of the word "essential". That's what I felt they should be. It was a great exercise because, if we're taking the physiology that literal and trying to make it look like arms weren't just stuck on -- How would your pectorals be if you actually had a second set of arms and what would their function be? They ended up coming across as a very noble-looking creature and first impression is a very huge thing, even for the character of Carter when he lands on the planet. That really got us inspired to always take that approach on everything.

We were talking to the dialect coach and she was mentioning that the Barsoom language was concocted the same way Na'vi was.

STANTON: Well, one of my producers, Colin Wilson, was one of my producers on "Avatar". He had a connection to the same dialect coach. I was a little nervous about it, because I didn't want to be ripping off or stealing or anything like that.

Are you worried about people making the comparison?

STANTON: Well, there's nothing we can do. That thing was on reels for a long, long time, but this book has been around for 100 years, I just want to see it. I've had the same pressure with other films I've had to make. "Oh no, someone else is making one just like it!" All that stuff. It all lasts for about three months -- it used to be six -- and it cycles before nobody gives a crap. It's about "is it a good movie and am I going to pull it off the shelf and watch it again?" I'm in it for the grandkids and I always am. I'm not in it for the short term. I'm in it for who might watch it after all the B.S. about box office and anything else controversial that can be created goes away. And it goes away almost faster than you can say it now. It's not worth getting caught up in. I've got a book that has held the test of time and I'm going to make a great movie out of it and hope it sails.

What was it about the book that has kept you so involved in the characters?

STANTON: Again, not to diss anything, but it was almost in spite of John Carter that I liked the books. That was where we put a lot of our work in. How to make him somebody to root for, not that I wouldn't. But it's not that unique to just this story. It's often that the hero is the least interesting person and that the interesting characters are the people around him. I felt like I'd rather watch damaged goods than somebody who has their act together. I went for someone who pretty much resigned himself to the fact that his purpose in life was over and sort of went with the thinking that it's not for us to say what our purpose in life is. You may think it's done or finished or ended or been missed, but life's not done with you sometimes. It may take awhile to figure out what your other purpose is or what your greater purpose always was. That's sort of the tact I took with Carter and it's really what made Carter perfect to play the role. He's the bad boy/wrong side of the tracks and that really worked a lot better.

Are you able to include any of the quote/unquote savagery that Carter had in the books?

STANTON: I used to laugh because it seemed like, in every chapter, there was the sentence, "And then I fought the greatest battle of my entire life." I went, "That can only happen once, technically!" We decided, Hey, it's an action movie. It's probably going to be two hours, two hours plus. I don't want to bludgeon the audience. I don't want to make it a gorefest. I don't want people to check out. I want every single battle to move the story forward. I want every single conflict to feel like it's different from another and special. You certainly want it to compound and feel like you haven't blown your wad early. You don't want the best thing to happen in the middle of the beginning of the film. We worked really hard to make tentpole scenes of conflict and saved or combined things to make them that much stronger. Because there was a lot of fighting to choose from. But we're trying very hard to make them feel like they felt in the books. For me, it was equal amount thrill of adventure and equal amount romance. At the end of the day, I felt like it was a romance. I've really tried to make that the bigger thread through the whole thing.

What have you done to the Deja Thoris character to make her more three-dimensional?

STANTON: That was my concern because we don't need another, "Yes, I'm a nuclear physicist." And yet I'm sure this book inspired people to do exactly that. I thought that I couldn't hide that she's technically a princess, but I can make sure she has as much investment and drive and as much of a goal if not more than Carter for why she's in the story. That's what I tried hard to do. But I wasn't going to hide from the femininity. I feel like that would be a knee-jerk, small-minded, male way of approaching it. I went for the tougher one of saying, "I'm going to embrace the sexiness, but I'm going to go at it from an almost asexual approach of, "Why? Why is she doing everything that she's doing?" Fortunately, someone like Lynn was a huge win because she brings such passion and strength and integrity to the thing. If the moment didn't service it, we had to bring it up to that when I was working with her. It's always a fine balance. You can't please everybody. I do, every now and then, peek on these blogs and see everyone saying, [Geek Voice] "Are they naked?! Are they naked on Mars?!" Use your brain! It's a Disney film! [Geek Voice] "Are they going to lay eggs?!" They might! Some might. Not everyone is going to be happy. I'm going to make it as solid a story as I can using as many elements as possible. Because they were introduced to me as a series as a kid -- which is a little ironic. I'm the guy at Pixar who is saying, "I don't want to do a sequel. I don't want to see a second 'Nemo'. I don't want to do a second 'WALL-E'" -- But I'm the guy saying, "I would love to see a series." Because that's how it was introduced to me. I've tried very hard, me and Mark and Michael Chabon, too, to think wider from the get-go before we ever set out on the first film. So in, touch wood, the event that this film is good enough that they ask for another, we have a plan. It's a good TV show that has meta issues that can evolve. But we also worked really hard to give it closure. Nothing bugs me more than a cliffhanger with the hubris to think that there is going to be a second one. It's been interesting. It's been fascinating to have that going in to something.

Where are the second and third films at this stage?

STANTON: We outlined three altogether. But the nice thing about not doing anything in tandem is that we can learn from the first and go, "Ooooh! I like that guy. I like that situation. Let's see if we can tweak that into the second and third." We're constantly growing and constantly adapting. We're trying to stay ahead of it. We're writing the second right now while we're working on the first... You know the cool thing we're doing is Nathan Crowley, who's our amazing production designer -- he did 'Dark Knight' and all of Nolan's films -- we came up with this idea of going around and finding geographical rock structure that already look like ruins and would just need a tiny bit of CG work to suddenly add a stairwell or a few window holes. It would flop into your eyes and look like a whole ruin, like Petra. We're making it look like it's bleeding off this whole mesa. That whole mesa is going to look like a city. And it you drive over to where we're shooting right now, that will be the entire city in a big, empty harbor basin. We won't need to do more than 20 percent CG work on top of the physical photography. Your eye will see 80% reality. Hopefully people will say, "Where the hell did you find that and where did you shoot it?" I thought it was a very clever way of grounding it reality and not in fantasy.

For more on John Carter:

Taylor Kitsch John Carter Set Visit Interview

Lynn Collins John Carter Set Visit Interview

Willem Dafoe and Thomas Haden Church John Carter Set Visit Interview