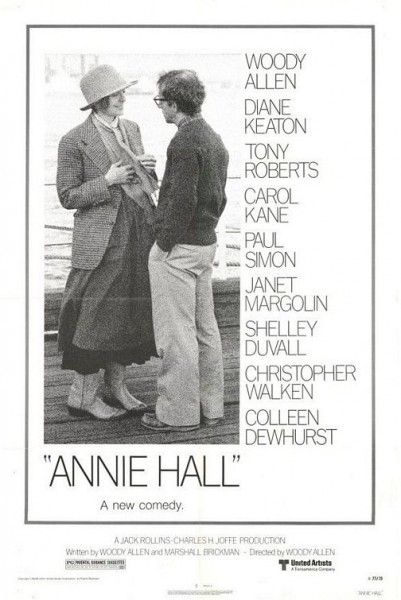

When every single man I knew started likening their budding sexual life in New York to that of Alvy Singer, Woody Allen’s protagonist in Annie Hall, my spidey sense should have been pounding like a Sunday morning migraine. Who exactly lionizes a condescending, judgmental intellectual-comic with a jones for Marcel Ophuls’ The Sorrow and the Pity and Marshall McLuhan? White, heterosexual men who had the unfortunate curse of having a few people tell them they’re funny and smart in their teens, that’s who. For the most part, that is.

At the time Annie Hall came into my orbit, these elements of Allen’s hardly veiled alter-ego didn’t really occur to me. What came through was a vast ocean of skepticism and sarcasm, an encyclopedic knowledge of the arts and politics, an ability to make women laugh, and the impossible possibilities of living, working, and socializing in New York City. When Singer made fun of the Great Western Wasteland known as Los Angeles, or was freaked out by the wayward social skills of the titular character’s Wisconsin family, including Christopher Walken’s Dwayne, I took that as gospel. The idea that there were smart, genuine people anywhere outside of the East Coast was simply ridiculous. When Allen pointed the wit of his script, or the allure of his images, at the Eastern elites and New York in general, the assumption was that he was just playing ball as not to look like a uppity intellectual alone in his high tower. It was a borderline meaningless concession.

Annie Hall first came to me on a VHS tape that my father had pilfered via a not-so-intricate, long-running scam against the good people at Columbia House, one that paved the way for my education in cinema early on. I’ve seen it since on the big screen – tip of the hat to NY’s Film Forum – as well as a number of times on DVD and Blu-ray. Before re-watching it for this piece, however, it had been a long while since I had seen Annie Hall and in the interim my attentions had drifted toward his oddities (Shadows and Fog, A Midsummer’s Night Sex Comedy) and later works, which have revealed an increasingly contemplative artist and well-aged comic mind at work. There are clearly no differences in the movie itself but having seen his recent spat of films (Café Society, Irrational Man, Midnight in Paris, etc.) and lived a little more life, the film’s still-bright brilliance comes from places that were of little or no interest to me beforehand.

The idea that Singer was being a bit ridiculous with his hatred for L.A. and unwavering devotion to NY never entered my mind before. He deploys Paul Simon brilliantly as a name-dropping whore of a music producer who speaks kindly enough but has the air of someone who thinks poverty is living on less than six digits a year. And in his usual self-deprecating manner, Allen makes enough critical evaluations about himself, including his intelligence and need to obsess on major philosophical notions of death, war, sex, and god. More importantly, his New York is rife with know-it-alls, pushy strangers, lunatic family members, old haunts, and resplendent views. Everyone always calls Allen a sucker for New York, which he is, but outside of his inability to confront widespread poverty in New York, which almost no one gets right in the movies, he’s also been very honest about it’ less-whimsical, more insufferable characteristics and characters. Often enough, he’s played them.

Allen put himself out as the self-effacing intellectual, someone who has read everything Freud put out but would rather sneak in some nookie or watch a Knicks game than converse with New Yorker writers. He’s also proven to be one of the most openly personal directors in popular culture, in America or anywhere, questioning universal moral and philosophical ideas with a rigorous skepticism and a not-subtle sense of the absurd. He includes a televised Dick Cavett appearance in Annie Hall, as well as nods to Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson, Ingmar Bergman’s Face to Face, modern sitcoms, Jack Nicholson and Anjelica Huston, and “The Denial of Death.” What leaps off the screen more than anything in Annie Hall at this point is its sense of modern personality, its constant confrontation with the present day and recognizable cultural and societal totems. Allen gave his characters lasting opinions, stupid and smart alike, that the audience could have conceivably been discussing on the line for the movie, much like the annoying man behind Allen who blasts Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits and Satyricon. He never allows any of his modern touches to feel flimsy or flippantly trotted out to quickly capture the audience’s attention.

The second to last time Singer sees Annie, he bumps into her on the streets of Manhattan, on her way to see The Sorrow and the Pity with the man she left Singer for. This leads to a bite to eat before they part for what must be forever and its notable that we remain locked in with Singer’s voiceover as these images pass by. There’s clearly still tenderness and attraction for one another, an unshakeable familiarity with each other, but the spark of challenge and compromise has been vanquished. Though there have been plenty of near-identical scenes to this in the wake of the film’s 1977 release, the ending still strikes me as strikingly true to life, different from my own experiences but unmistakably from a true experience that could have caused an entire change of existential course. In revisiting his memories of Annie with a modern self-awareness, he essentially considers a whole other life he might have led.

The ending is echoed in the haunted reunion of Jesse Eisenberg and Kristen Stewart’s characters in Café Society, in which a scarring romance and desire seemed to continue percolating underneath a new, vaguely content life. There’s a lot less romance to the romance in Café Society, and it’s easy to see how certain critics would confuse ambivalence with carelessness. One could still hear remorse and regret and doubt in Singer’s voice when he talked about Annie and their time together. In comparison, his voice-over for Café Society sounds as if he’s reading from a stark, not particularly well-written novel, as if he’s defaulted to total fiction as his mode of expressionism. It’s not entirely surprising but still galvanizing that he has taken to considering the moral and psychological weight of murder and criminality in his most robust late-period works, such as Match Point, Blue Jasmine, Cassandra’s Dream, and the aforementioned, sensational Irrational Man.

It’s in Irrational Man that Allen confronts the concept of committing a righteous killing – not one done out of self-interest or compulsion but out of philosophical curiosity and the feeling of balancing the cosmic scales. Considering all the very serious allegations levied at Allen over the years, it’s a risky proposition to suggest such, er, moral limberness but it’s an enveloping, fascinating work of self-interrogation at the very least and easily the best film of his late period alongside Midnight in Paris. And yet, I can still see Singer behind all of Allen’s later-period narratives, raising his hand to give a complicated answer to an impossible question before rightly ridiculing that very same answer endlessly. He still imagines himself as a man of great intellect but also sees the darkness in his character, one that has bore plenty of controversies, many of which remain unresolvable at this point. The most recent allegations from Dylan Farrow are impossible to ignore and pushed at least one of my friends to opine that this would be a great time for Allen to retire for good. It would probably be for the best but Allen doesn't seem to be slowing down and anyone who has been following the filmmaker over these years knows that, no matter the caliber of his artistry, he rarely does what's best for him or the world around him. That's one thing that hasn't changed over time and is unlikely to be questioned in the time that remains.