It takes real talent to make a film look distinct. Sure, there are a variety of tools at a filmmaker’s disposal, and various combinations of cameras and lenses and lights that can create differing images, but more often than not—especially in the wake of the advent of digital photography—a lot of films have started to look rather same-y. Which is why the YA adaptation The Sun Is Also a Star (which is in theaters now) is such a breath of fresh air. Not only is the film shot in anamorphic, but the image carries with it this lived-in texture that is at once cinematic and grounded, making this timely love story all the more realistic.

When I saw that first trailer for The Sun Is Also a Star, I immediately took notice of who shot the film, and I jumped at the chance to speak with cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw about her work on the movie. While I was excited to discuss Durald Arkapaw’s unique approach to this New York-set story, and the challenges she faced shooting a city that is as iconic as it is ubiquitous in the world of film, I was delighted to find Durald Arkapaw also had plenty of insightful thoughts about the state of cinematography today, how she goes about making an image feel distinct, and what it’s like working as a woman in an overwhelmingly male-dominated field.

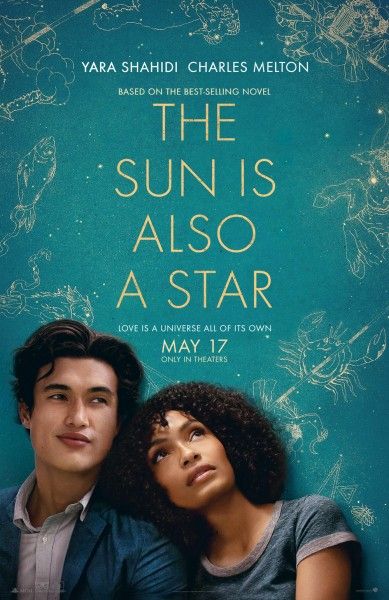

For those unfamiliar, The Sun Is Also a Star is based on the book of the same name by Nicola Yoon and stars Yara Shahidi (Black-ish) as a Jamaica-born woman named Natasha who meets and falls in love with a college-bound romantic named Daniel (Charles Melton) in the course of a single day. However, as her family faces deportation and with hours left on her last day in the U.S., Natasha finds herself fighting against the world—and her own feelings.

During the course of our interview, Durald Arkapaw talked about her collaboration process with director Ry Russo-Young, how she purposely wanted to make the film better-looking than some other YA adaptations out there, the challenges involved in shooting a movie that takes place over the course of a single day, and how she was able to bring texture to the images onscreen. Durald Arkapaw also revealed who she looked to as influences when she first became a cinematographer, offering her own advice for aspiring cinematographers. And given that the field of cinematography is heavily dominated by men, she spoke to her experience as a female DP and how the industry is finally progressing.

I’ve interviewed a lot of cinematographers and I have to be honest, this was one of my favorite conversations I've ever had. As you’ll see, Durald Arkapaw is not only insightful, but also refreshingly candid about her process and the industry. She’s someone who clearly puts a lot of thought and effort into her craft, and the proof is in the pudding onscreen.

Check out the full interview below. The Sun Is Also a Star is now playing in theaters.

How did you first get involved with The Sun is Also a Star?

AUTUMN DURALD ARKAPAW: It kind of happened in a roundabout way because I didn't know the director and the director didn't know me. And I think one of her creative producers that she's worked with on some of her other independent projects recommended me to her. So then we ended up meeting, and through that meeting, that's how I found out about her work. I wasn't actually about to take on a project for the summer, but she kind of kept checking in with me as she was getting her crew going. And also I think they were having her mostly meet with people that were New York based, and I'm based in Los Angeles. So yeah, we just kind of met casually and just kept talking. And then down the line she said that she'd really like me to do it. At that time, I was more open to doing it and going to New York. Things kind of fell into place. That's how we met. So it's sort of a more roundabout way than I normally meet people on projects. I work with a lot of directors I know or I'm friends with and stuff like that.

I'm always curious about the relationship between the director and the cinematographer, so what were the early conversations about the vision for the film like?

DURALD ARKAPAW: I think what's interesting about this project, more so than other teen movies I've done [like Palo Alto and One and Two], is Ry's take on it was she didn't wanna recycle and do another bright, sharp teen film that a studio is going to put out. Even her treatment and how she described it and what she saw in my work, it was kind of like let's approach this and do something new under the studio umbrella with a novel everyone loves. And it's got a diverse cast and a very on point subject matter. So that was appealing to me. I think her approach on it was what appealed to me the most, and then also the love story in Manhattan, kind of Woody Allen aspect of it. So earlier on, I already knew that she wanted to take a more natural, textural approach. She wasn't afraid of moodier lighting and something that didn't really speak to what we had seen before in that genre. And references like Blue Valentine and Fish Tank and stuff like that in which the world feels real and it doesn't feel like everyone's on a set with a bunch of lights around and always looking bright. She wanted to shoot it anamorphic, which I loved. Yeah, her whole treatment spoke to me. The aerial shots. She really thought about having scope and so we were in line with our tastes as far as what we saw for the film. And I feel like it's something new for that genre. Because we're used to the stuff that they’ve put out before, based off of books, which has been in my opinion not great looking.

Yeah yeah. No I would agree with that. A lot of them have a same-y bland feeling almost. Not only is this unique for that genre, it's also unique for New York movies. And there are a lot of New York movies and there are a lot of ways to shoot New York. Can you talk about approaching the city in a way that makes it feel distinct?

DURALD ARKAPAW: Yeah, I love New York, as cliché as that sounds. I've spent a lot of time there as a young person and I had one of my first loves happen in New York. So that's something that was very touching to me as far as them meeting each other on the streets of New York, which has happened to me. So the sentimentality of that was touching.

But yeah, I've spent a lot of time there and I always loved New York films. If I'm searching for something to watch and it's one of those moods where you just want something that's gonna make you happy and nostalgic, I search for them. So I've seen a lot of them. And I'm sure that kind of informed how I shoot it when I do work there. But Woody Allen is one of my favorite directors and has been an inspiration to me starting out as a DP, and the work that he did with Gordon Willis. So I already had Manhattan on the brain and Ry wanted to shoot scope. And so I tried to, as much as I could, infuse that inspiration in the way that I was framing it and any chances that I got, as far as textural elements and different shots of the city that I could put in there.

But yeah, I'm familiar with that format. So as far as how my eye naturally sees, because I do so much in anamorphic, it was easy for me to jump into a city that I find is very tall, but also has so much scope in the information that you get on the sides is so important. Not only just because there are skyscrapers, but you can get wide and far away as well. These two characters coming together, that cliché thing that everyone talks about. But in this instance you've got them traveling through the city from one end to the other in one day. Trying to meet together. So what a perfect format. It was just perfect to show that distance, but also that togetherness. So that was fun. And then also doing the aerials and filling out the whole city, as far as getting a view from a different perspective, not just from the ground where they mostly were walking around.

You mentioned that it takes place over the course of a single day. I imagine that presents its own unique challenges as a cinematographer, especially in terms of lighting. How did you approach that and showing the day progressing, in terms of the lighting and the shot composition and stuff?

DURALD ARKAPAW: Yeah that was tough, but challenges don't really deter me from projects. But thinking about shooting something like this in the summer in New York where weather is so haphazard, it could say it's raining the day before and it not rain. Or it could say it's not raining and then it rains. These are things on my mind. But there was a lot of time and effort that our team put into planning, with the first AD and Ry and I making sure we had a plan for when things could go wrong and cover sets. That's really the best way to tackle something like that first off.

And then secondly, just really matching with lighting. Matching and diffusing light and having a consistency. Keeping track of that. I'm big on lighting so it's something that I'm always doing. But in this case, having a great crew and just kind of keeping an eye on it. But also, in the script, as they're traveling along, you're very aware of the moments where they're reaching the end of the day and things should be back lit. I use flares a lot, so that's something that also helps with always making the sun present. Sometimes I'm using lights as flares just to kind of give that sense, even if was a flatter day. And I was really impressed with the cut of the film put together by the editor. They did such a good job with the flow. I didn't really question it at all. They kind of move in and out of the space, like inside to outside, in a great way that makes you feel like you are going through a day and not that things change too much.

Well in shooting in New York City, I imagine that collaboration with the production designer is also pretty key. What were those conversations like as you were moving from set to set and trying to make each sequence feel distinct and interesting from a visual standpoint?

DURALD ARKAPAW: I hadn't worked with this production designer before, but I adore him now. He's one of my favorites. His name's Wynn Thomas. He's pretty much a legend. He came up with Spike Lee and has done most of Spike's films, and he's based in New York. So he knows the city very, very well and the areas that we were shooting. You know, Upper Harlem. Most of the stuff he had done before. So he was just so valuable to our team and inspiring. I learned a lot. So it was really beautiful to have that collaboration with him. Instead of say, for instance, someone that was coming in from another city or that didn't know New York as well. Yeah, his insight was super valuable. Just about texture. Mostly he has such a soulfulness about the space and the character feeling together. And I think that's something that I find very important in my job when I work with production designers like that. Where obviously they're not only thinking about the visuals, but they're thinking about how this affects character and the texture of things and color contrast and all those things. So he's an ace, obviously, in that department, but also I just share that love for character that he does. The emotional aspect of how the design affects the lighting and the image, he's very in tune with. We had a lot of conversations about that. I think that's why I really enjoyed working with him, because he has similar tastes and that always helps.

You mentioned the anamorphic, which I think is a really smart and interesting choice. And if I'm not mistaken this was shot digitally, but you used older lenses. I was wondering if you could talk about that. Because it feels so textured and tangible and real. When so many movies you see nowadays, they just feel so flat and kind of boring.

DURALD ARKAPAW: Yeah, no I'm with you that. Because I think it's an interesting time. It has been for a while. It’s interesting because I've encountered some times where, with resolution and, for instance, 4K deliverables, sometimes you have a team of people that want something more resolute and sharp. And then you have another audience that appreciates texture. And then you have the awards season come out where a lot of the majority of the films are shot on film. So it's very interesting to see the diversity of format, but I come from a film background. Most of the stuff I shot when I was at school was film. And I still love shooting film when I can still shoot it. I think, for me as a DP, what originally drew me to this career path were things shot on film in anamorphic. So as far as my love for visuals, it comes from that. So I'm always trying to make it look as filmic as I can and as textured as I can.

It doesn't necessarily mean that something that is shot on film has to be not as sharp or resolute. But it does have to have some type of soulfulness and texture. So I gravitate toward older lenses when I shoot digital. I do prefer the Alexa, as far as the censor and filmic curve that it offers. However I've shot RED as well. Like Palo Alto was shot on the RED. No matter what the tool, I'm always leaning more towards lighting the film more filmic and how I expose it, and what stop I shoot those types of lenses at. Because I'm pretty much a Panavision shooter, so I'm very familiar with those lenses and how they resolve. But I think the more you shoot, the more you get used to the lenses.

Well it looks terrific. I can't say the same about some other stuff. So I think that speaks to your craft and talent here.

DURALD ARKAPAW: No, I appreciate that. And I saw your article when that came out and I thought that was lovely. So thank you for that comment. I appreciate that.

Oh sure. Well I was curious if you could talk a little bit about who were some of your influences as you were honing your craft and honing your skill as a cinematographer? What were the films you were watching? Who were the people you looked up to?

DURALD ARKAPAW: I kind of found film a little later in life, as far as I didn't go to undergrad and study film. I studied art history and then minored in photography. So I've always done something in the visual arts. But it wasn't until later that I went to AFI for doing my Masters program. After my undergrad in art, I just started getting into watching films and going to symposiums and listening to Q&A's after films that would come to the ArcLight, stuff like that. And then started to apply to film school.

At the time, I was really gravitating toward Harris Savides’ work and Roger Deakins and Gordon Willis. Those were my favorites, and it's funny how you talk to people now and you find those names on everyone's list. But I think at the time it didn't really feel like I was doing what everyone else was doing. It just felt like, when I saw these certain films from these guys, they just spoke to me as far as their photography. And they're all very different.

But I think what spoke to me about Deakins was I really like a naturalistic looking film. And that's what I really love about his work, especially the work that he does with the Coen Brothers. It feels very, very real and beautiful. But it is lit and it does have a punch to it and a style to it that elevates the image from maybe more of a documentary look. But I remember looking it up and he had started in documentaries. So that was something I appreciated, because I did as well and you really learn light when you do those types of projects, because you're working with what's around you and you're paying attention to how natural light is falling on things. So I think that's something important that it's nice to start in that avenue and then learn how to light with units after you're practicing with the sun and stuff like that.

And then Harris, I've always loved his work and how textured it feels. So I like DP's that kind of throw their own personality in the works, and you can see that over time. But also their collaborations with various directors, they really are storytellers for that director. But they also find a way of infusing their own personality as well.

Yeah definitely. Those are my favorite cinematographers as well. I mean there are some that are kind of chameleon-like, but, I don't know, I like the idea of a little bit of an authorship to it.

DURALD ARKAPAW: Yeah, for sure. Back in the day you saw resumes where they're dabbling in different genres, and I just spoke to this recently in this podcast that I did because my friend, who's also a DP, and I were just talking about how it seems to be a bit more pigeonholed now. Where you shoot one thing and everyone only thinks that you can just do that. Whereas, back in the day, it was more about being a storyteller and being hired for your craft, and then finding the story together. But also for your expertise. That's just happening a lot less these days. Where there are way more DPs. The market's over-saturated. Everyone wants things to look the same. Commercial work is being seen a bit more. TV is being seen a bit more. Those references and those DPs are still inspirational for that as well. Just the variety of work, but also, like you said, just seeing their personality throughout different genres, and not just doing the same thing over and over.

And I like seeing someone like Rob Hardy, for example, going from Annihilation to Mission: Impossible - Fallout. Those are very different films, but you can feel it's him. And he brings something interesting to the action genre.

DURALD ARKAPAW: Oh yeah, no totally. I loved Fallout. It was one of my favorites.

Oh me too. I'm obsessed with that movie.

DURALD ARKAPAW: Yeah, for sure.

What advice would you give to young people that are thinking about maybe becoming a cinematographer? Or maybe looking towards that as a career path? In terms of what should they be thinking about or what's something they could do to broaden their horizons?

DURALD ARKAPAW: I often speak at AFI and then do interviews about that question that you just asked. It found me in an odd way as well, is that I didn't really know it existed as a career. I had to seek it out. And then also, as a woman, I only became aware that women weren't doing this job when I actually looked it up. So when I wanted to become a DP, I just thought, "Oh, let me find out what this job is and then I'll just go do it. I'll just take the steps to kind of become that person." And then as I was looking up who shot more things that I loved, I was like, "Oh so a lot of dudes are doing this and not very many women." However, because I love the film Blow, I saw that Ellen Kuras did it and I thought, "Oh that's amazing." So early on, I saw that there was a woman doing it. So that really inspired me. Just the light bulb went off. It was like, "Okay if there's one woman doing it, then there can be two. Or there can be three."

So that's how I found it. But that way, I think, is very rare in the sense that nowadays there are more women. We do speak up and there are more inspirations that you see in the general public. It's been great to see that growing and I get a lot of messages about like, "Yeah, I'd love to help you out. What can I do?" And I always like to answer, "Just keep seeking any opportunity you can to make images.” Because essentially that's what it is. That's kind of what I did. When I first found out that I wanted to become a DP and work on sets, I just said yes to anything that put me in that environment. Even though it probably wasn't directly informing me becoming a DP at the time.

But yeah, I think it's about composing images and pay attention. I find that these days, there's so many visuals out there and there's a lot of copying or making things look exactly like other people. What inspired me before was just traveling and looking at various things. And then kind of coming up with your own stories and shooting little films with your friends. I did a lot of that. So for me, the advice I'd give would be about paying attention and making images. It doesn't always have to be like you have to be on some big set. Or you don't have to have a job where you're getting paid shooting. All these little things can inform your point of view.

I think that's what you need these days, breaking in. Because there are so many people, things are starting to look similar, that if I'm looking for someone new, I'm looking for someone to infuse their personality and where they've been into the image. Not just copying what Roger Deakins does or stuff like that. That's why I think we may gravitate towards the work that Rob Hardy did on Mission: Impossible because we've all seen those Mission: Impossible movies. Even down to when John Woo did his. I remember watching that one, and I loved that one as well. Every one of those films is so different, and I loved what Rob Hardy brought to that film. That comes with who he is, his experience, and what his eyes see. So as much as you can infuse your personality and your taste and soulfulness into it, I think that's what the younger generation should pay more attention to.

And to that point, it's insane that there are so few female DPs, given that the camera is the point of view of so many of these films. Having a woman running that department brings a different POV to it. So I'm glad that you're out there and people like Rachel Morrison are out there. And I hope there are more.

DURALD ARKAPAW: Yeah, no definitely. I appreciate that. I think once the door is opened then people know they can walk through it. It's inevitable that it just starts in numbers. There's so many times in the last year that I worked with male directors and they're like, "This is the first time I've worked with a woman." And then it went well. Then it was just like it became a no-brainer. It just has to happen to change, I suppose.