Tim Burton was having a good year in 1985. His debut feature, Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, opened that August to admittedly mixed reviews but had gone on to make a little under $41 million at the domestic box office. After years of working in Disney’s animation department, Burton had made a movie that spoke to his love and unwavering dedication to all things bizarre, scary, and putrid, despite it being penned by Michael Varhol, Paul Reubens, and the late Phil Hartman. Burton served up Pee-Wee’s journey into the vast, unpredictable strangeness of America as a twist on De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves and for all the Tequila dances bike-hospital nightmares, Burton was essentially after the same ghost that De Sica was: what does one do when one’s fellow man has wounded you for no apparent reason other than self-regard? To put it another way: what exactly is to be done with the normies?

It’s a question that would come to hang over not just his follow-up, 1988’s Beetlejuice, but also much of the American auteur’s catalog. Batman and Batman Returns turned American cityscapes into grand stages for maniacs, only one of whom had a specific desire to save the everyday people of the populace. Edward Scissorhands found the inexplicable creature of the title dealing with the pullulating violence lying at the heart of suburban life, brought to the foreground by the simplest rupture in its rigid formula. It wasn’t until Big Fish arrived that Burton, by then an established top-shelf director, husband, and father, seemed to suggest that the experiences and imagination of the everyday worker could paint the world as vividly as a genuine outsider.

With Beetlejuice, however, Burton was clearly still in a growth spurt of creative boldness; the inherent rebelliousness of his tales matched an audacious visual style anchored to a wildly expressionistic eye for design. When the script first came to Burton, it was reportedly much darker and had Michael Keaton’s Ghost with the Most as a literal demon, who rapes and kills members of the Deets family. Michael McDowell and Batman scribe Warren Skarren have the screenplay credit, and they are responsible for turning Beetlejuice into something far more exciting and wondrously macabre than the simplistic, sadistic horror one-off it might have been.

And yet, horror is key to Burton’s sense of world building, and character building for that fact. When Adam and Barbara Maitland (Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis) die, we don’t even see their bodies. They remain essentially intact until Charles, Delia, and Lydia Deets – played by Jeffrey Jones, Catherine O’Hara, and Winona Ryder – arrive and their initial, amateurish attempt to scare them is to use basic slasher violence. Delia and the radiantly pretentious Otho (the late, great Glenn Shadix) blow past when Barbara hangs herself in the closet and rips her face off. Decapitating Adam doesn’t do anything to get their attention either.

It’s not until they learn a bit from afterlife manager Juno (Sylvia Sidney), as well as some time reading their Handbook for the Recently Deceased and endure alse starts involving bed sheets, that they seemingly grasp the idea of the uncanny. Visually, Burton crafts a positively beguiling vision of the afterlife, marked less by blood and gore than sheer oddness. In effect, the director is arguing for a less dogmatic view of death and for a far more beguiling place for the restless dead.

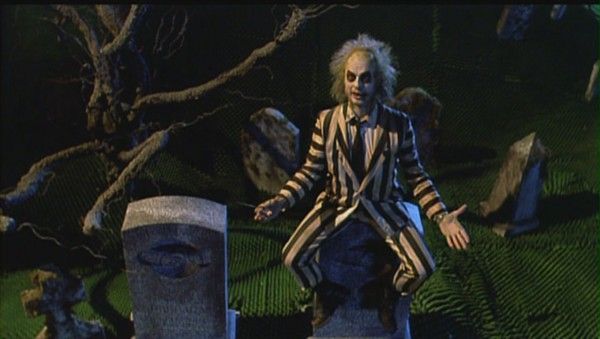

Of course, with their ability to pull off complex tricks like the famous “Day-O” sequence also comes the knowledge of professional ghosts, specifically the titular malevolent spirit, the former pupil of Juno. Hungry for bugs, rotting away, and aggressively horny, the snarling and snorting spirit of giddy horror embraces the decadences of the afterlife, living off freelance haunting jobs . Coming off his first film only three years earlier, Burton saw himself split here between the doe-eyed yet talented and inventive ghosts and a cynical phantom devoid of moral compass or much taste at all. Keaton’s electrifying and immersive performance turns the character into something far more grotesque and convincingly undead, overtaken by fits of picking at himself and eating critters but also slickly confident when selling the goods. It’s Burton’s nightmare of what a life working in Hollywood might do to him.

In essence, he turns the Deets family into a reflection of Burton’s financiers and backers, those who are tasked with the inevitable commodification of the Maitlands’ talents as ghosts. The script avoids painting the entire family as money-grubbing fools. In fact, the capitalistic urge in Charles and, ultimately, Delia is seen as a natural impulse, not unlike deciding to take a shower. The argument at the core of Charles’ frankly underreported business plan is whether or not you can make a business out of being creeped out but not scared. And its in forcing Adam and Barbara to appear for Charles, Delia, and Otho through exorcism that they deplete the Maitlands of their abilities and the limited existence they are afforded. It’s also what makes them call on the scary guy.

In no other work does Burton’s true fears about himself feel so potentely realized as they do here, deployed as a malevolent freelance specter with his eyes on a marriage to Lydia that will make him corporeal. Its also where the director most directly showcases himself as a homebody and a lovebird – he married Lena Gieseke while in production on the film. Two years later, Batman came out and not only laid further foundation for comic-book blockbusters in the wake of the Superman franchise flameout but suggested that it was the ideal mode for the new class of stylish auteurs. If he would push some of his supporters with the darker corners explored in Batman Returns, he also made the most stylistically substantial and intimate comic book adaptation with it.

The great triumph of Beetlejuice is that it’s the rambunctious work of an auteur primed to bloom in the coming years into a big-studio favorite with a inarguably impressive resume. A sequel – set in Hawaii – was planned but never came to fruition and now there’s word that a sequel will finally happen with Keaton returning and Burton involved in some capacity. Burton remains a pretty personal director – Dark Shadows, Frankenweenie, and Sweeney Todd are capital-g Great – and there is a chance that Burton’s return to hos own vision of himself as a wandering ghoul, selling frights for a livelihood, could yield a satisfyingly searching work for Burton. Let’s hope that remains the case as he puts the final touches on his adaptation of Dumbo, one of Disney’s new line of CGI remakes of their whole catalog. Like Barbara and Adam, it would seem that Burton has found a secure if not entirely ideal house to haunt, with living people that at least find them entertaining