One of the great elements of the script for Rocky, as more than a few admirers have noted, is that the Italian Stallion, played by writer-producer Sylvester Stallone, loses his fight with Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers). The subsequent Rocky films, unfortunately, never even come close to this sort of shaggy humbleness, infuriatingly reiterating for five sequels that Balboa is unquestionably the best fighter, and best man, that America has to offer. Which is to say that he’s the best fighter and man in the world. The fact that we never quite get that same melancholic timbre, that sense of personal triumph despite (temporary) professional failure, in the other Rocky movies suggests that monetary success and fame does, in fact, corrupt even the most seemingly honest, simple, and noble of characters, whether it be Balboa or Stallone.

Great boxing movies, of which Rocky is merely one of a few dozen, are often about the greatness of the body, which often hides a brash, complex, and even dangerous fury of thought, aimed at politics, race, social constructs, sexuality, and anxious morality. Like great horror films and great comedies, these films are centralized between the life of the body and the life of the mind, both of which sustain tremendous amount of damage. At the same time, seeing as boxing has often viewed as a “low” sport, films like Raging Bull, Requiem for a Heavyweight, and The Set-Up are intrinsically about matters of class, tales of young and old men with little money and a rather incredible threshold for physical pain and decimation.

And yet, like any sub-genre, there are no exact rules to what these films express. As new masterworks about fighters continue to be produced, from David O. Russell’s The Fighter to Frederick Wiseman’s hypnotic Boxing Gym, the bounds of what the stories of boxers, both fictional and all-too real, can or should be continue to move or simply disintegrate. What’s intoxicating about this specific subject matter, however, has rarely changed: the brutal, romantic view of athleticism, the ghastly yet unrelenting seductiveness of violence, and the undeniable pleasure and effectiveness of a rags-to-riches story, amongst other things. Where these films often fail, when they do, is when they only focus on the last of that triptych, seeing only the hope that drives these men, while only feigning interest in the ferocious anger, haunted pasts, greed, hunger, bigotry, and other unpleasant desires and hang-ups that inform men who like to fight.

Here are the ten best boxing movies that avoid that pitfall and, as a result, have become major or minor classics.

Boxing Gym

Frederick Wiseman’s primary interest is the mechanics of institutions, from the day-to-day operations and unique events planned in Central Park to the homes, businesses, and associations that make up a Queens community in his latest, In Jackson Heights. In the case of Boxing Gym, one of his shortest and most striking works, he takes his verité style to a Texas gym where fighters train, kids learn the sport, and aged specialists teach and form fighters that could be tomorrow’s champions. Wiseman gets at the intimate details of not only the sounds and action that populate the sport, far away from the cameras of HBO, On Demand, or ESPN, but how small athletic businesses are budgeted, run, and kept up, including customer relations. And though Wiseman’s subtly direct style might sound tedious, the director’s unimpeachable sense of rhythmic editing and tight, perfectly composed shots radiate the unmistakable persona of the filmmaker’s political, societal, and personal ideas.

Raging Bull

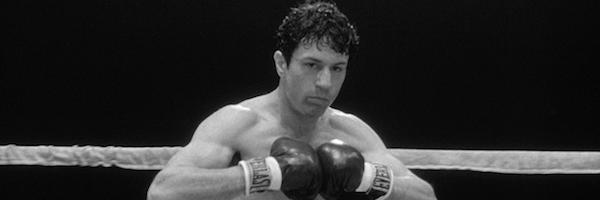

Every movie on this list would likely make my top-ten list for the particular year of its release, but only this one places in my top ten films of all time. Martin Scorsese’s unrelenting masterpiece, one of a dozen or so that the New York-based director is responsible for, confronts the startling life story of Jake LaMotta, played by Robert DeNiro in the crowning achievement of an astonishing career, who went from being an unbeatable powerhouse in the ring to an out-of-shape, bullish MC at a ramshackle dive bar. Shot in grainy, unkempt black-and-white, formed by swift yet carefully considered cuts and peerless long takes, Scorsese tracks the very base of the masculine mind, so easily rattled by suspicion, pride, and ego, and considers violence, both professional and otherwise, the destructive and often fatal outcome of insecure men.

Raging Bull’s fight scenes are so dazzlingly urgent, so patiently considered and yet so unexpected in form, that one almost forgets how wrenching yet unsentimental the drama outside the ring is. Sure, everyone remembers when DeNiro asks his brother (Joe Pesci) if he fucked his wife (Cathy Moriarty, at her very best), but the sequence at the local pool, at the ritzy club, and in the abusive LaMotta home are just as revealing of the inherent, insidious weakness of machismo, without denying the base attraction that fighting and brute strength exude to this day.

Fat City

Between Oscar winners and hugely influential Hollywood productions, from The Maltese Falcon and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre to The African Queen and The Man Who Would Be King, the great John Huston helmed this haunting tale of lost and revitalized talent in the wilds of California. Stacy Keach is Tully, a former fighter now picking fruit and vegetables with migrant workers to support an unquenchable thirst for the booze, and Huston gives the environs a similarly shambling, wrecked atmosphere of cheap hotel rooms, filthy dive bars, and shops plastered with faded photos and posters.

Tully gets a shot in the arm when he begins hanging out with Ernie (Jeff Bridges), a talented teenaged fighter, but the rejuvenation, for both men, is short-lived, due in no small part to Tully’s ex-manager (Nicholas Colastano). The scenes of training and fighting ache with the experience of an old, addled pro, with ample help from Leonard Gardner’s script, but it’s Huston’s work with Conrad Hall, one of the smartest DPs to ever pick up a camera, that makes Fat City so deeply moving. Lost in a nowhere California town, Huston sees the promise of the future as clearly as he sees the bleakness of that same destination, one which cannot be fought with a forceful jab.

Ali

Up until his most recent work, the fascinating yet flaccid Blackhat, Michael Mann had one of the more admirable winning streaks in the modern America cinema, though he’s increasingly been met with indifference. And though Collateral showed a renewed interest in his menacing crime stories, the disinterest began with this magnificent biopic of Muhammad Ali, played by a sublimely cocky yet sensitive and perceptive Will Smith, who goes beyond mere mimicry to find both the firebrand political figure and an unrelenting fighter of unparalleled talents. In the ring, Mann stays close with his actor, and there’s a stunning balance of the boxer’s exacting, forceful strength and limber movements, to say nothing of the outsized personality that made him so impossible to ignore.

There’s both eloquence and energy to the fights, and Mann makes the drama just as palpably effective, especially when Ali goes to Africa for the Rumble in the Jungle against George Foreman. With his camera running through the roads of Africa alongside Smith, Mann captures the source of Ali’s disarming strength amongst children and excited onlookers, while simultaneously expressing just how far-reaching the great man’s outspoken ideals were, and continue to be.

Hard Times

Walter Hill’s stunning debut doesn’t focus on professional boxing but rather the bare-knuckled variety, the kind of fighting done in dank, dilapidated warehouses, fishing docks, and garages. It’s where Charles Bronson’s Chaney, a wanderer with little more than a jacket and a bundle for his knick-knacks, makes his living, and when he partners with the smooth-talking Speed, played by James Coburn, he finds himself on the road to making enough money to leave it all behind, and maybe even make an honest lady of a local prostitute. Chaney is an unyielding boxer of tremendous strength, but Speed is weak with pride and money, which gets them in trouble with a variety of Louisiana hoods. Shot beautifully by Philip H. Lathrop, the DP behind Hill’s The Driver as well, the film is a lean story of tough men in tough times, seeing violence as a trade only to be entered into when absolutely necessary and certainly not something to be proud of. Even more than that, Hard Times offers a reflection of Hill, a filmmaker always perched on the age of Hollywood’s big-budget abyss but whose no-bullshit demeanor has never meshed well with the thoughtless whims of producers with their eyes on the accounts rather than the screen.

Million Dollar Baby

Forever misunderstood by both the far right and the far left, Clint Eastwood seemingly found a rare happy medium with Million Dollar Baby, the story of an old pro trainer, played by the filmmaker, and a young female fighter with ambition to spare, embodied by a funny, fierce, and deeply moving Hillary Swank. What emerges here, more than anything else, is the prickly, endearing relationship that forms between trainer and trainee, and Eastwood, working from Paul Haggis’ lovely script, neither entertains ridiculous romantic ideas or condescending father-daughter allusions, unless you’re specifically looking for the latter. Instead, Eastwood revels in their professional admiration and occasionally colliding concepts of physical technique, while the subtext suggests that his ability to be emotionally direct and supportive needs as much work as her uppercut. It’s ultimately a film about the grave briefness of life, one which Eastwood paints in dark color tones, like that of a tombstone, and tinges with notions about the almighty. Nevertheless, he finds a rampant pulse of life underneath the melancholy, as much in the exemplary, stunningly paced fight scenes as the vast array of supporting characters, from Oscar-winner Morgan Freeman and Luke Cage himself Mike Colter to Jay Baruchel and Anthony Mackie.

The Fighter

David O. Russell has a way of injecting his New Hollywood-aping dramas with an ample dose of comedic anxiousness, matched by a masterful talent for the long take, and these elements have rarely blended so potently as they do in The Fighter. Following the slow-moving ascension of “Irish” Micky Ward (Mark Wahlberg) to top-tier champion, Russell highlights the fighter’s personal and familial issues as much as his training regiment and title fights, which lends the narrative a rare dramatic fullness, a sense of a life lived as much outside the ring as inside. The director finds a thrilling immediacy in the fights, pivoting and ducking with his camera like Ward does, but its in the raucous verbal assaults and unseemly happenings of the Ward clan, inhabited most prominently with intensity and wild humor by Melissa Leo and Christian Bale, as well as his blooming romance with a local bartender (Amy Adams), that Russell finds Micky’s bruised heart. And at the same time, he finds an apt analogy for himself, an artist who continues to buck at the stale normalcy of middlebrow Oscar-bait pictures.

Requiem for a Heavyweight

This might count as a bit of a cheat, as there isn’t much fighting in Ralph Nelson’s shattering, noir-tinged melodrama after the startling opening moments, featuring the one-and-only Muhammad Ali in a rare dramatic cameo. The entire opening is seen in a POV shot from the perspective of “Mountain” Rivera (Anthony Quinn), an aging boxer who is told that he must hang it up after Ali knocks his block off, and this lean, bracingly tragic film tracks what happens after an athlete can no longer use his body for a living. The narrative lays out two options for Rivera: either become a costumed wrestler for yucks and some extra money, or teach young boxers at a summer camp and, later, a gym.

It’s a question that’s as applicable to fighters as it is to actors, or any sort of skilled professional, and as always, it’s greed that weighs most heavy in the decision, most specifically for Mountain’s duplicitous manager, Maish (Jackie Gleason). Based off a teleplay by The Twilight Zone head Rod Serling, Requiem for a Heavyweight locates a sadness familiar to anyone who has ever known the sweetness of hard-earned triumph: the enveloping helplessness and bitter struggle of the inevitable decline, which so often ends in the same realm of miserable mockery as where we see Rivera in the final shot.

The Set-Up

At 73-minutes, it almost makes sense that Robert Wise’s remarkably direct The Set-Up was based on a poem by Joseph Moncure March, and there’s a kind of touch poeticism to this tightly edited noir. Wise’s film stars the great Robert Ryan as “Stoker” Thompson, an over-the-hill boxer looking to take on young upstart Tiger Nelson (Hal Baylor), but as always, the real drama of the film is going on in the background. Stoker’s manager, tellingly nicknamed Tiny (George Tobias), and the fighter’s wife, Julie (Audrey Totter), are essentially fighting for Stoker’s very life, pitting comfort and love against ambition, pride, and money. It’s all pure B-movie artistry but Wise, working from Art Cohn’s excellent script, laces the film with shadowy menace, creating an intoxicating visual balance between the darkness of the streets, stadium hallways, and backrooms against the big, bright lights that hang over the ring. Cohn’s script nails the terminology, fatalism, and training methods without a measure of piousness, but it’s Wise who gives the film its tragic sense that life away from the lights is a place of isolationism and hurt that not even men as strong as Stoker can easily walk into.

When We Were Kings

The Rumble in the Jungle fight barely makes up a quarter of Michael Mann’s Ali, and yet it was the kind of event that deserves massive documentation, investigation, and consideration. Thankfully, that’s exactly what the fight got and the result was this fleet, fantastic documentary chronicling the lead-up to Muhammad Ali’s fight with George Foreman. Friends, pundits, professionals, and managerial sorts discuss the chances on both sides of the ring, but also bring up notions of race, money, and behavior while the boxers are seen training, talking smack, and discussing their opinions of the match-up with journalists. Ali is seen as a confident, witty wise-cracker, while Foreman is all imposing and brooding, and the camera hangs on both men enough to see the strength and weakness of both attitudes, hinting at psychological undercurrents for the fighters. It’s a movie that I would have happily sat through with double the runtime, but at a quick 88 minutes, Leon Gast’s film strikes with the swiftness of Ali and the force of Foreman.