Despite its current reputation as arguably the best film the 1990s produced, GoodFellas didn’t even crack the top 25 box office hits of 1990, getting edged out by another classic of sorts: Hard to Kill. As far as crime films go, the Steven Seagal revenge thriller remains disposable, if marginally engaging, trash, the kind of film that became mass-produced following the introduction of Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Bruce Willis, to say nothing of Mel Gibson, Dolph Lundgren, and Jean-Claude Van Damme. The films made by these men are all familiar for a myriad of reasons, but most noticeably for their stressing of the unrealistic conflict of the pure and good facing off against the corrupt and deeply evil. The villains in these movies are not men or women who have lived complicated lives that have led them to their penchants for murder and torture, but rather, they are demonic psychopaths hell-bent on destroying all that is decent in the world. It’s an understandable, comforting fantasy, but one that ultimately reveals an offending cowardice, a refusal to understand that criminals are shaped by their environment and the unique circumstances of their lives, not simply conjured by Lucifer himself.

In September of that year, however, GoodFellas came out and shattered that concept on several different levels, depicting the life of Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) and his friends in New York’s Italian Mafia in a written and visual style both morally complex and politically daring. The film, directed by Martin Scorsese -- still America’s most inventive and consistently provocative filmmaker -- neither completely vilified these men nor depicted them as absolute or even enviable in their powers to lie, cheat, steal, and kill their way to the easy life. Henry, along with Jimmy (Robert DeNiro) and Tommy (Joe Pesci), are men addicted to the feeling of undue respect and domination, and like any other kind of addict, they grow pathetic and weak when their sense of control is even mildly criticized. The only thing that truly protects their fragile, borderline infantile sense of self are guns and money, and Scorsese’s main focus throughout GoodFellas is the corruptive power of those two elements. It’s telling that when Henry hands Janice (Lorraine Bracco), his soon-to-be-wife, a gun to hide, after he beats her attempted rapist with it, Scorsese ever-so-slightly utilizes slow-motion to express the drug-like high the pistol stirs up in her. “I got to admit, it turned me on,” she says in the voiceover, and it’s that very same attraction that Henry, Tommy, and Jimmy are desperately clinging to.

As inarguably intoxicating, unsettling, and hugely funny as GoodFellas is on its own, its release was followed quickly by two other remarkable crime films of a similar narrative focus, namely Abel Ferrara’s astonishing King of New York and Miller’s Crossing, the Coen brothers’ witty, ponderous take on the Irish mob. Though neither Ferrara’s icy opus nor the Coens’ wise-ass wonder retain the sublime frankness and challenging humanity of Goodfellas, as a triptych, these films have become touchstones of modern film noirs and crime films, alongside other candidates for the best crime movies of 1990, such as Pulp Fiction and Carlito’s Way. Each one takes an essential villain for its protagonist, tapping into a radical strain of empathy and a wildly inventive criticism of human nature’s more self-obsessed, indulgent tendencies, the groundwork for which was laid by hard-boiled gangster classics like Raoul Walsh’s gloriously unhinged White Heat.

Miller’s Crossing is the most distinctly period-obsessed film of the lot, with its narrative unraveling during Prohibition, some two decades before White Heat hit theaters. The booze, however, is hardly the focus of the Coens’ film. Rather, it’s the relationship between mob head Leo O’Bannon (Albert Finney) and his number two, Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne), which hits a major speed bump when Leo refuses to put a hit out on Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro), the duplicitous and weasel-like brother to his main squeeze (Marcia Gay Harden), to quell a beef with Italian crime boss Caspar (Jon Polito). The issue is complicated by the fact that Leo’s squeeze is also sleeping with Reagan, and the plot grows even more convoluted from there, but that would seemingly be the point. It’s Reagan’s disposition, and the way that he speaks, that command loyalty and trust from his fellow gangsters, seemingly always two steps ahead of everyone yet not a particularly good fighter or endearing to anyone.

Reagan is stylish but, as we come to find out, he’s also cold and empty, and at first glance, one might say the same thing about Miller’s Crossing: an aesthetically acute and devilishly snappy work of style with no real substance. Catchy lingo like “what’s the rumpus” or “giving me the hi-hat” would seemingly be there simply as well-placed hooks, but the film ultimately plays like more of a cautionary tale for the kind of films that are strictly style without substance. It would be one thing if Reagan was seen as heroic or even unshakably cool, but he’s not, as evidenced by several times when he looks to be almost killed or beaten mercilessly; the film’s most revealing moment is when he foolishly trips while attempting to sneak up and kill Bernie. Despite being a love-fool and a sucker, Leo is a far more admirable person, filled with philosophical contradictions and all-too-human imperfections. The Coens are outwardly warning of the coldness of cynicism, even as their sardonic perspective makes for such irresistible dialogue. To grow entirely cynical is to lose sight of being human, which the Coens openly demonstrate with Reagan in his mistakes and slip-ups, and being human often involves being just a bit of a clown, which true cynicism hardly abides by.

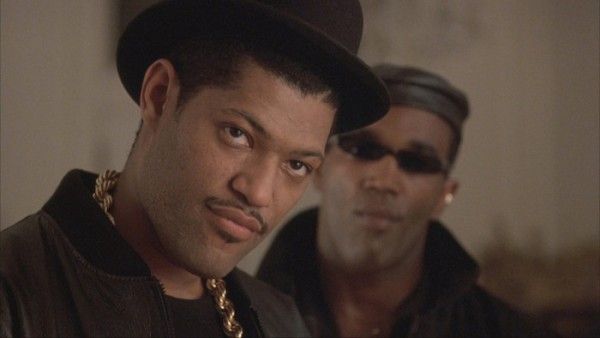

This is in stark contrast to the chilling, sleek imagery of King of New York, which casts the great Christopher Walken as Frank White, a crime kingpin recently released from a long stint in prison, returning to the titular city to reclaim his throne. The core of the film is Frank’s feud with a gaggle of police officers, led by Victor Argo’s Roy Bishop, and the narrative complicates the would-be moral divide between police and thieves. White, aided by his notorious number two, Jimmy Jump (Laurence Fishburne), kills gangsters who feed off their communities and give nothing back, whereas Bishop’s squad ultimately goes behind their leader’s back to assassinate White and his colleagues.

Ferrara films all of this with equal parts shadow and gleam, to reflect this complexity visually, but the veneer actually matches the contemplative themes of Ferrara’s film. In one scene, he offers a job to a group of young African-American men who try to stick him and his girlfriend up; it’s a job in crime, but it’s also a paying job. In fact, most of White’s crew is African-American, whereas the cops are almost entirely white, with the lone exception of Wesley Snipes’ Tommy. If a criminal is charitable and benefits the community, and the cops designate themselves as righteous executioners, do their titles matter anymore? It’s a familiar concept, but Ferrara doesn’t see White as a Robin Hood -- as he still enjoys his drugs, guns, and murder -- and the cops are similarly empathetic in their desperation and exhaustion brought on by trying to stop drug sales. The demonizing and illegality of drugs has allowed for White to become something like a local hero, and has turned the cops into homicidal gunman, looking for the easy satisfaction that their firearms supply.

The film also represents the artistic struggle of Ferrara himself, an erstwhile director of trashy B-movies who suddenly turned big-time auteur by turning this pulp-novel crime story into something like high art. The matter of money is never far from Ferrara’s mind, and his cold yet striking vision suggests both the luxury that money provides and the emotional disconnect that often comes with greed. Ferrara’s New York is hell frozen over, whereas Scorsese’s New York is something far more paranoid and unpredictable, but money and honor are the concepts that bind these two films, as well as Miller’s Crossing. King of New York sees the opulence that money gives you, whereas GoodFellas sees the fun and carelessness that money affords. There is a corrupted but nevertheless potent sense of honor in White, whereas Henry, Jimmy, and Tommy are only honorable until the money runs out or their life is on the line. And in the case of Miller’s Crossing, honor is something that’s only as good as the words used to express it, much like ideas in films are only as good as the images used to express them.

The sting to all of this is that, especially with Miller’s Crossing and King of New York, the aesthetic and the style was all that many filmmakers took from those films, and one can see their influence in everyone from Chris Nolan and Matthew Vaughn to Doug Liman and James Mangold. These directors are not without their better works, or even masterpieces, but scripts, rather than the rhythms of editing or the details of composition and motion drive their films; only Nolan expresses some sincere sense of texture in his films. And to list all the films that have been influenced by or are straight-up rip-offs of GoodFellas and Scorsese’s style would take up another 800 words easily, but there have rarely been crime films that have reverberated so personally with the people making them. Scorsese faces not only the darker elements of his cultural heritage but also his own fantasies of wealth and hedonism when Henry talks about always wanting to be a gangster, and he shows the bracing high of that lifestyle as often as he shows its damning aftermath. Ironically, had any of these artists been more absolutist about the power of wealth and style, painting them either as forces of good for all or a poisonous facade, their films would probably have made a lot more money at the box office.