Tomorrow, Gangster Squad hits theaters (click here for my review). The crime flick takes place in 1949 Los Angeles during mobster Mickey Cohen's rise to power in the City of Angels. America has had a fascination with the gangster throughout cinema history. They've been seen as folk heroes and the scourge of society. In the era of the Production Code, Hollywood tried to have it both ways with mandated-warnings paired with exhilarating, charismatic characters. Gangsters may always fall, but it's a thrilling, infamous ride.I've compiled a list of five gangster movies worth checking out. To stay in line with Gangster Squad, all of these films were made before 1950, so they lived in the era of the glamorous underworld and all the seedy, ruthless behavior it entailed. Hit the jump to check out the list.The Public Enemy (1931) Like most of the movies on this list, The Public Enemy is billed as a cautionary tale. The film revolves around Tom Powers (James Cagney), a bad seed who grows up mean, and is always looking for the easy buck. Like other classic gangsters, he has an intense devotion to his family, but there's also tension stemming from Tom's rivalry with his brother, Mike (Donald Cook). The movie plays from Tom's childhood to his death like an evil version of It's a Wonderful Life.While other gangster films will use their protagonist as a direct warning to the audience, The Public Enemy is a little more subtle, and uses Tom's lifelong friend Matt Doyle (Edward Woods) as the morally conflicted gangster. We see that corporal punishment has no effect on Tom, which tells us that there's no saving him. Matt, on the other hand, is the character who has a choice, and The Public Enemy tells the "Matts" in the audience to be wary of characters like Tom. Naturally, Tom has to have a fall, and his line "I ain't so tough!" may as well be "Crime doesn't pay!"I also have to take note of James Cagney's performance since he's the actor who bookends this list. Cagney is not a timeless actor, but an actor perfectly of his time. His vocal affectation and exaggerated performance scream vaudeville (his profession before becoming an actor), but there's no doubting his charisma. He may play one of cinema's least convincing teenagers (he was 32 when The Public Enemy came out), but his performance in this film always has the hint of a beating heart you can barely hear beneath his cold exterior.Little Caesar (1931)

Like most of the movies on this list, The Public Enemy is billed as a cautionary tale. The film revolves around Tom Powers (James Cagney), a bad seed who grows up mean, and is always looking for the easy buck. Like other classic gangsters, he has an intense devotion to his family, but there's also tension stemming from Tom's rivalry with his brother, Mike (Donald Cook). The movie plays from Tom's childhood to his death like an evil version of It's a Wonderful Life.While other gangster films will use their protagonist as a direct warning to the audience, The Public Enemy is a little more subtle, and uses Tom's lifelong friend Matt Doyle (Edward Woods) as the morally conflicted gangster. We see that corporal punishment has no effect on Tom, which tells us that there's no saving him. Matt, on the other hand, is the character who has a choice, and The Public Enemy tells the "Matts" in the audience to be wary of characters like Tom. Naturally, Tom has to have a fall, and his line "I ain't so tough!" may as well be "Crime doesn't pay!"I also have to take note of James Cagney's performance since he's the actor who bookends this list. Cagney is not a timeless actor, but an actor perfectly of his time. His vocal affectation and exaggerated performance scream vaudeville (his profession before becoming an actor), but there's no doubting his charisma. He may play one of cinema's least convincing teenagers (he was 32 when The Public Enemy came out), but his performance in this film always has the hint of a beating heart you can barely hear beneath his cold exterior.Little Caesar (1931) There are two kinds of warnings in these Production Code-era gangster movies: political or biblical. Little Caesar opens with Matthew 26:52's "for all who draw the sword will die by the sword." Little Caesar a.k.a "Rico" (Edward G. Robinson) is eager to draw his sword from the get-go, but the movie is no great tragedy. It's a pulpy pleasure, and Rico makes Tom Powers look like a paragon of compassion by comparison.Like other gangsters on this list, the protagonist has to rise to power, which inevitably leads to slaying his higher-ups. It's like All About Eve, but with Tommy Guns. While Powers is a company man who has a friendly relationship with his boss, Rico is almost foaming at the mouth at the prospect of running an organization. He sees a great and glorious destiny, and relishes the amount of blood he'll shed on the way to the top.That's one of the tricks of these gangster movies. For audiences living in The Great Depression, they don't want preaching. They want entertainment. They want escapism. They want something to give them a look at the other side. If the world is unfair, then why play by the rules? It's a henchman's tale, but it's also one of the underdogs. Men like Rico and Tony from Scarface might be on the wrong side of the law, but they have the same American Dream: fame and fortune. These Hollywood gangster films are like delicious candy that allows the audience to gorge for 90 minutes, and then the Production Code says candy is bad for you.M (1931)

There are two kinds of warnings in these Production Code-era gangster movies: political or biblical. Little Caesar opens with Matthew 26:52's "for all who draw the sword will die by the sword." Little Caesar a.k.a "Rico" (Edward G. Robinson) is eager to draw his sword from the get-go, but the movie is no great tragedy. It's a pulpy pleasure, and Rico makes Tom Powers look like a paragon of compassion by comparison.Like other gangsters on this list, the protagonist has to rise to power, which inevitably leads to slaying his higher-ups. It's like All About Eve, but with Tommy Guns. While Powers is a company man who has a friendly relationship with his boss, Rico is almost foaming at the mouth at the prospect of running an organization. He sees a great and glorious destiny, and relishes the amount of blood he'll shed on the way to the top.That's one of the tricks of these gangster movies. For audiences living in The Great Depression, they don't want preaching. They want entertainment. They want escapism. They want something to give them a look at the other side. If the world is unfair, then why play by the rules? It's a henchman's tale, but it's also one of the underdogs. Men like Rico and Tony from Scarface might be on the wrong side of the law, but they have the same American Dream: fame and fortune. These Hollywood gangster films are like delicious candy that allows the audience to gorge for 90 minutes, and then the Production Code says candy is bad for you.M (1931) M is a huge outlier on this list, but I felt it was essential to include for several reasons. First, it provides a nice contrast to what Hollywood was doing with its gangsters as opposed to what was happening in Germany where they didn't have the Production Code. Second, it makes gangsters more powerful than the cops rather than a tragic group who will surely get their comeuppance. Finally, M has nothing to do with teaching the audience a lesson. Rather, it forces the viewer to consider dimensions of justice: who is responsible for it? What makes justice different than revenge? If morality is dictated by pragmatism, then what's practical about killing murderers?The conflict of M revolves around the attempts to catch Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), a child murderer that has driven a German city into chaos.  Paranoia reigns among the citizens, and the cops are at a loss for how to catch the killer. Their attempt at creating a dragnet is seriously, albeit indirectly, hurting business in the underworld. The gang bosses decide that they should hunt down the killer, and they use a network of beggars to find Beckert. When they catch him, they make the odd decision to bring him to a perverse trial of mob justice. There, Lorre gives an unforgettable performance as Beckert explains that he can't help himself, so how can he be held responsible for his actions?It's fascinating to watch the cops and criminals attempting to achieve a similar goal rather than being directly at odds. There's no question that Beckert is evil and that we can be allowed to side with the criminals in this endeavor. But then we have to ask if the end justifies the means, and what is the end we're hoping to justify? Despite dealing with complicated questions, director Fritz Lang made a film as tense and breathless as the other gangster movies on this list. His accomplishment is made even more remarkable when you consider the film's brilliant use of sound even though sound in motion pictures was a relatively new technology.Scarface (1932)

M is a huge outlier on this list, but I felt it was essential to include for several reasons. First, it provides a nice contrast to what Hollywood was doing with its gangsters as opposed to what was happening in Germany where they didn't have the Production Code. Second, it makes gangsters more powerful than the cops rather than a tragic group who will surely get their comeuppance. Finally, M has nothing to do with teaching the audience a lesson. Rather, it forces the viewer to consider dimensions of justice: who is responsible for it? What makes justice different than revenge? If morality is dictated by pragmatism, then what's practical about killing murderers?The conflict of M revolves around the attempts to catch Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), a child murderer that has driven a German city into chaos.  Paranoia reigns among the citizens, and the cops are at a loss for how to catch the killer. Their attempt at creating a dragnet is seriously, albeit indirectly, hurting business in the underworld. The gang bosses decide that they should hunt down the killer, and they use a network of beggars to find Beckert. When they catch him, they make the odd decision to bring him to a perverse trial of mob justice. There, Lorre gives an unforgettable performance as Beckert explains that he can't help himself, so how can he be held responsible for his actions?It's fascinating to watch the cops and criminals attempting to achieve a similar goal rather than being directly at odds. There's no question that Beckert is evil and that we can be allowed to side with the criminals in this endeavor. But then we have to ask if the end justifies the means, and what is the end we're hoping to justify? Despite dealing with complicated questions, director Fritz Lang made a film as tense and breathless as the other gangster movies on this list. His accomplishment is made even more remarkable when you consider the film's brilliant use of sound even though sound in motion pictures was a relatively new technology.Scarface (1932) Forget Brian De Palma's bloated and cartoony 1983 remake. Howard Hawks' 1932 original is far more fun and in some ways nastier when you consider the time period. Tony Montana may have a chainsaw and a little friend, but the way Tony (Paul Muni) casually guns down a guy in a hospital bed is just as disturbing. It also helps that Muni is absolutely terrific as the ruthless gangster whose lust for power is rivaled only by his unsettling obsession with his sister's chastity.Whereas Little Caesar looks to the Bible as a warning to its audience, Scarface is a direct call to arms for the government (the original title was Scarface: Shame of a Nation). The film is a masterpiece of lip service. Hawks makes a fantastic, rapid-fire action flick centered on a magnetic, charismatic psychopath who somehow becomes even crazier when he gets his hands on a gun. Then the film turns around and has a scene where minor characters have a discussion about the role government must play in bringing down the criminal underworld.Hawks doesn't necessarily mock this point of view, but the action scenes speak louder than words. When you're using a machine gun to shoot the pages off a calendar in order to show the passage of time, there's not a serious aversion to violence. If anything, Scarface isn't a warning to Americans but a criticism of the American dream where a Great Gatsby-esque sign flashes outside Tony's window. The sign reads, "The World Is Yours".White Heat (1949)

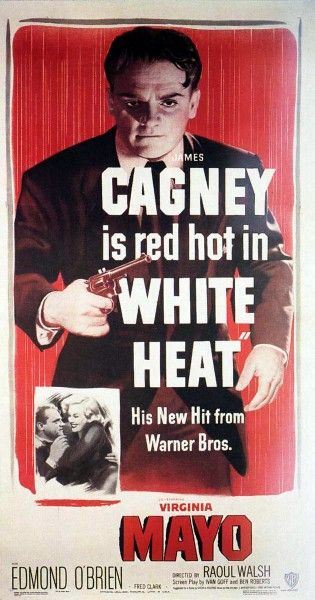

Forget Brian De Palma's bloated and cartoony 1983 remake. Howard Hawks' 1932 original is far more fun and in some ways nastier when you consider the time period. Tony Montana may have a chainsaw and a little friend, but the way Tony (Paul Muni) casually guns down a guy in a hospital bed is just as disturbing. It also helps that Muni is absolutely terrific as the ruthless gangster whose lust for power is rivaled only by his unsettling obsession with his sister's chastity.Whereas Little Caesar looks to the Bible as a warning to its audience, Scarface is a direct call to arms for the government (the original title was Scarface: Shame of a Nation). The film is a masterpiece of lip service. Hawks makes a fantastic, rapid-fire action flick centered on a magnetic, charismatic psychopath who somehow becomes even crazier when he gets his hands on a gun. Then the film turns around and has a scene where minor characters have a discussion about the role government must play in bringing down the criminal underworld.Hawks doesn't necessarily mock this point of view, but the action scenes speak louder than words. When you're using a machine gun to shoot the pages off a calendar in order to show the passage of time, there's not a serious aversion to violence. If anything, Scarface isn't a warning to Americans but a criticism of the American dream where a Great Gatsby-esque sign flashes outside Tony's window. The sign reads, "The World Is Yours".White Heat (1949) White Heat returns us to Cagney in arguably the greatest performance of his career. With 18 more years of experience under his belt, Cagney loses his vaudeville affectations, but none of his intensity. While The Public Enemy is moralistic, White Heat carries an air of tragedy. Cody Jarrett (Cagney) is undoubtedly a despicable creature, but he has a similarity to Hans Beckert where we feel an ounce of compassion for someone who can't help what he has become. Cody's enemies may be at his mercy, but he's at the mercy of his mother's indulgence, epilepsy, and desire to be loved.Unlike Tom, Tony, or Rico, White Heat gives us a gangster who answers to no one. There's no rise-fall narrative at work, and by 1949, the Production Code lacked the teeth it once had. It's difficult to moralize about violent city streets after the violence of a World War.  Cody must still be "punished", but White Heat never feels like a lesson. Instead, White Heat is allowed to live on its own terms as a taut, exciting tale of heists, chases, escapes, and betrayals. Cops in the 1930s Hollywood films could only shake their fists at mobsters and wait for the fall to come. The cops in White Heat take an active role, and cleverly, smarter cops imply smarter criminals.Coming at the end of the 1940s, after the Great Depression and World War II, White Heat encapsulates the values of earlier gangster films without feeling like a throwback. White Heat is highly reminiscent of Scarface in both the character's psychopathic devotion to a family member (in this case, the mother) and his endless ambition ("Top of the world!", Cody famously shouts at the end of the film), but it's unapologetic in its motives, pacing, and desire to thrill the audience. There's no speech to the audience about what must be done about the criminals. We may not want to be gangsters, but we can't help but find them absolutely captivating.

White Heat returns us to Cagney in arguably the greatest performance of his career. With 18 more years of experience under his belt, Cagney loses his vaudeville affectations, but none of his intensity. While The Public Enemy is moralistic, White Heat carries an air of tragedy. Cody Jarrett (Cagney) is undoubtedly a despicable creature, but he has a similarity to Hans Beckert where we feel an ounce of compassion for someone who can't help what he has become. Cody's enemies may be at his mercy, but he's at the mercy of his mother's indulgence, epilepsy, and desire to be loved.Unlike Tom, Tony, or Rico, White Heat gives us a gangster who answers to no one. There's no rise-fall narrative at work, and by 1949, the Production Code lacked the teeth it once had. It's difficult to moralize about violent city streets after the violence of a World War.  Cody must still be "punished", but White Heat never feels like a lesson. Instead, White Heat is allowed to live on its own terms as a taut, exciting tale of heists, chases, escapes, and betrayals. Cops in the 1930s Hollywood films could only shake their fists at mobsters and wait for the fall to come. The cops in White Heat take an active role, and cleverly, smarter cops imply smarter criminals.Coming at the end of the 1940s, after the Great Depression and World War II, White Heat encapsulates the values of earlier gangster films without feeling like a throwback. White Heat is highly reminiscent of Scarface in both the character's psychopathic devotion to a family member (in this case, the mother) and his endless ambition ("Top of the world!", Cody famously shouts at the end of the film), but it's unapologetic in its motives, pacing, and desire to thrill the audience. There's no speech to the audience about what must be done about the criminals. We may not want to be gangsters, but we can't help but find them absolutely captivating.