Making a great movie is not an easy task, but if a filmmaker succeeds in getting just about everything right, it still hinges on one thing: the ending. How are you going to let the audience out of your story? What do you want them thinking about as they leave the theater? What feeling do you want to stick with them? Getting all of this across on top of wrapping up your story can be tricky, and more often than not the ending is more of a footnote than anything—not as memorable as what came before.

But a precious few films are able to take the conclusion to new heights, offering up a final scene or shot that viewers are unable to shake. This may come on the heels of a massive plot twist, it may be a genius visual idea that taps into the film’s thematic throughline, or it may be a frustratingly/excitingly ambiguous note that leaves a portion of the conclusion up to the viewer.

There’s no math equation that gives you a great ending. There’s no formula you can stick to in order to guarantee a brilliant conclusion. That’s part of what makes great endings so memorable—they don’t happen too often. Below, we’ve rounded up a few of our favorites from cinema history. They run the gamut from tearful to joyous to delightfully twisted, but they all have one thing in common: they’re unforgettable. Behold the best movie endings of all time.

Oh, and spoiler alert, obviously.

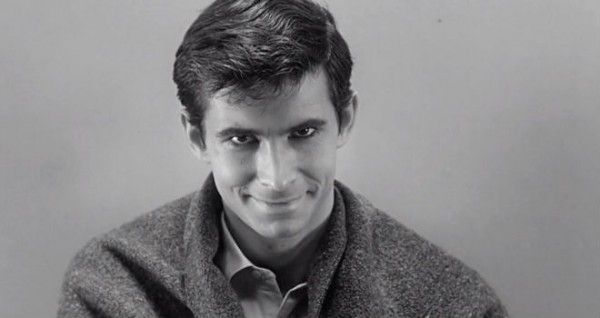

Psycho (1960)

Before M. Night Shyamalan or The Coen Brothers, there was Alfred Hitchcock—and boy did he know how to end a movie. Obviously the most famous Hitchcock ending of all time comes in the form of Psycho, which not only throws the audience for a loop at the end of the first act by killing off perceived protagonist Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), but offers a doozy of a twist at the end of the film. The audience is led to believe that Norman Bates’ (Anthony Perkins) mother is the one who killed Marion in the shower earlier in the film, and thus the tension continues to play out. But when Sam (John Gavin) and Lila (Vera Miles) venture to the Bates Motel to question Norman’s mother, it’s revealed that Norman’s mother is nothing but a rotting corpse in chair. In the film’s final moments, Norman sits alone in a room at the courthouse, having been outed as the real murderer. A psychiatrist explains that Norman murdered his mother, but out of guilt exhumed her corpse and began acting as if she was still alive, sometimes pretending he himself was his mother. For the final shot, we close in on Norman’s face as the voice of his mother plays in his head, claiming she wouldn’t hurt a fly. The murders were all Norman’s doing. All the while Norman gets this devilish smirk on his face. Roll credits.

Hitchcock was a consummate entertainer, and Psycho is a perfect example of the filmmaker using every trick in the book to take his audience on a thrill ride from beginning to end. The twist ending not only makes perfect sense (it was inspired by true-life serial killer Ed Gein), but leaves the audience’s jaw on the floor as the lights come up in the theater. – Adam Chitwood

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Heartbreak is hell and memory is a cage that keeps us there, but could we ever escape the lure of love, lust, and all its perils, even if we knew for sure we were doomed to fail? Probably not. In Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Joel (Jim Carrey) and Clem (Kate Winslet) discover just that after a devastating breakup leads the impulsive Clem to erase Joel from her memory for good via an experimental new procedure. Naturally, Joel decides to do the same and the bulk of the film follows his desperate attempts to thwart that decision as his memories of the woman he loves are stripped from his mind one by one. At the end of the film, Joel and Clem stand face-to-face, no memory of their relationship, but with the knowledge that they were once in love and the irresistible desire to give it another shot. They know they're all but certain to end in pain, that they're proven bad fit, and that trying again will only break their hearts. Okay. Laughing and crying and desperate not to feel lost and alone, they accept it. That's ok. That's the cost of putting yourself on the line for love and that's just fine. Eternal Sunshine boasts plenty of clever camerawork and narrative innovation, but the simple, honest emotional truth of its final frames cement it as a classic. — Haleigh Foutch

Inception (2010)

The film that spawned a thousand reddit theories. Christopher Nolan is known for his twisty narratives, but Inception pushed that to the limit as Nolan presents four stories happening simultaneously at wildly different paces, tracking a team of “extractors” incepting the mind of a corporate heir. The emotional throughline of the film is Leonardo DiCaprio’s Dom Cobb, who lives in exile as his wife framed him for her murder back in the U.S. He dreams of seeing his children again, and at the film’s end, as the team has seemingly completed its mission successfully, Dom is finally reunited with his children. The camera pans to a spinning top—the sign of whether one is still dreaming—but cuts to black before the audience ever knows for sure whether it falls over. What’s important here is not whether Dom is dreaming or not, but how he feels. That’s the brilliance of this ending—narratively it offers an ominous conclusion, but emotionally it’s 100% satisfying. Dom is happy. Whether he’s trapped in dreamland or not, he’s finally at peace. – Adam Chitwood

E.T. (1982)

E.T. is Steven Spielberg at the top of his game, and he’s a living legend. It’s not just that the ending is emotional or powerful. It’s that the entire movie earns the farewell between E.T. and Elliott, so that when it races to its climactic finish and heartfelt good-bye between its two leads, you can feel what’s been gained and lost in the moment. The scene also functions as the culmination of the film’s themes where Elliott finds some peace with his parents’ divorce, learning how he can “be good” and still loved even when someone he loves leaves him. It’s absolutely beautiful. – Matt Goldberg

Se7en (1995)

Go ahead and say it, you know you want to. We can do it together. “What’s in the box?!” Se7en’s ending has become iconic and endlessly quoted because it’s a perfectly crafted culmination of an intricately threaded film that cements John Doe (Kevin Spacey) as one of the best film villains of all time. Scripted by Andrew Kevin Walker and directed by David Fincher, Se7en stars Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman as Taylor and Somerset, two detectives on the hunt for the biblical serial killer John Doe, who hunts down his victims according to the seven deadly sins. Methodical and precise, and always one step ahead, John Doe leaves behind a string of deviant tableaus inspired by his victim’s deadly sins, and he saves his best for last. Just when the detectives think they have the upper hand, Doe reveals his full hand — they were always in his trap. He wins. And they become the final pieces to complete his life’s hideous work. A box is delivered, and the decapitated head of Taylor's wife is inside it. In that instance he becomes Rage, and falling in lock-step with the killer's plan, he executes John Doe in cold blood -- a fate Doe set for himself, punishment for his sins of Envy.

It’s disturbing and expertly crafted, and it’s easy to see why it’s become one of the most famous “twist” endings of all time. It’s also easy to see why the studio mandated the brief coda that follows, that delivers a salve in the form of a Hemingway quote. Fincher fought for the film to end in blackness; he wanted the audience to sit with the brutality. But he needn’t have worried, because Seven’s ending sits with you for years. — Haleigh Foutch

There Will Be Blood (2008)

This is what’s called a “mic drop.” Paul Thomas Anderson already crafted one pretty terrific (and big) ending with Boogie Nights, but when it came to closing out his 2008 opus There Will Be Blood, he took no prisoners. After spending over two hours with Daniel Day-Lewis’ Daniel Plainview, the audience comes to understand what makes this bad dude tick. We see his life ebb and flow, and the film’s final act shifts forward in time to when Plainview is a wealthy—if lonely—oil tycoon. But a visit from Paul Dano’s Eli Sunday lifts his spirits in the most nefarious way, and the long-held tension between these two characters comes to a bloody end. “I’m finished!” still stands as one of the best—and most striking—closing lines in cinema history – Adam Chitwood

The Social Network (2010)

One of the most expertly constructed films in recent memory, The Social Network packs a punch from beginning to end. While many balked at David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin tackling “a Facebook movie,” the finished film is a prescient narrative of power plays in the 21st century—movers and shakers are not fiftysomething men, they’re teenaged geniuses thrown into the deep end without the emotional maturity to handle such dangerous waters. As the film concludes with Jesse Eisenberg’s Mark Zuckerberg rich and powerful, the camera lingers as he refreshes (and refreshes, and refreshes) the Facebook page of his former girlfriend. The one whose breakup may or may not have spurred something inside him to create one of the most successful ventures in history. He may have all the money and power in the world, but at what cost? To what end? – Adam Chitwood

Les Diaboliques (1955)

Les Diaboliques is an OG of movie twists, and an essential thriller that set the stage for generations of mysteries and film noir that would follow. Henri-Georges Clouzot's 1955 French feature stars Michel Delassalle (Paul Meurisse) as a bitter, tyrannical headmaster hated by his wife (Vera Clouzot) and mistress (Simon Signoret), who conspire to murder him. But his body goes missing, hijinks ensue, and it turns out Michel was never dead at all; instead, he and his mistress were conspiring the whole time, setting the stage to trigger his wife’s weak heart and literally scare her to death. At the time, Les Diaboliques' ending was revolutionary and mind-blowing (and it still packs quite a punch today), and it’s become the basis for countless twisting tales of deception to follow, from countless film noir classics to Wild Things. — Haleigh Foutch

Vertigo (1958)

Arguably Hitchcock’s most twisted film, the culmination of his fascinating examination of the male gaze (James Stewart’s Scottie is the epitome of the male gaze and yet Hitchcock is just as guilty of this obsession) ends when our hero seemingly gets everything he wants—the woman he loves is alive, he’s conquered his Vertigo, he’s solved the mystery—and yet through dumb luck and circumstance, she falls to her death. His obsession and guilt will never end, and he will always be consumed. It’s a powerful metaphor for the nature of cinema, both as a viewer and an artist. – Matt Goldberg

Scream (1996)

Slasher movie endings had become so predictable and paint-by-numbers Carol Clover wrote a whole book about it (Men, Women and Chainsaws) and coined the phrase “final girl”; a horror trope that’s still in effect to this day. Penned by screenwriter Kevin Williamson, Wes Craven’s 1996 meta-slasher Scream was constructed by a creative team who knew those tropes in and out, embracing them and subverting them in just the right measure, culminating in a final act reveal that layers on the surprises and sticks the landing with subtle, smart deconstruction of your standard slasher standoff. Not one killer, but two! Including the final girl's supposedly dead boyfriend! Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell) is the “final girl”, but in her movie, she gets to break the rules and live anyway, giving Scream a refreshing distance from the inherent puritanical leanings of horror's traditional moral metrics, and genuinely surprising the audience in turn. Slasher movies have never been the same after Scream, and the surefire ending is proof in the pudding that self-reflective horror can be more than a gimmick -- in fact, it can change all the rules. –Haleigh Foutch

Before Sunset (2004)

The most unlikely sequel in history, Before Sunset is a masterpiece. Richard Linklater revisits his Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy) characters nine years after the events of Before Sunrise, this time tracking their day-long conversation in real-time. The movie sets up a ticking clock—a plane Jesse has to catch—that makes every word of their conversation precious, and as we watch these characters fall back in love (or realize they’ve always been in love), the pain of their inevitable separation lingers. But Linklater, Hawke, and Delpy brilliantly refuse to take the obvious route for the film’s conclusion, as Jesse has followed Celine back up to her place and settled into a relaxed position, minutes before he has to leave. Celine’s final words—“Baby, you’re gonna miss that plane”—are music to the audience’s ears, as we see that maybe these two will end up together after all. – Adam Chitwood

La La Land (2016)

It’s been two years since La La Land hit theaters, which I’m pretty sure is enough time to safely say it has one of the best movie endings ever. The musical romance takes a shocking turn in its third act, jumping forward to an epilogue in which our lead romantic duo are no longer together, and haven’t been for some time. Emma Stone’s Mia, now a famous actress, goes out to dinner with her husband when they stumble upon a popular jazz club—Sebastian’s (Ryan Gosling) Seb’s. But instead of devolving into a “happy” ending where Mia and Sebastian end up together, writer/director Damien Chazelle instead opts to show us what their lives would have been like had they made a couple of decisions differently—in musical form, obviously. It’s one of the most emotional few minutes of cinema in recent memory, and the pang of regret and “could-have-been’s” stings hard. But that familiarity is exactly what makes this ending so damn effective. – Adam Chitwood

Fargo (1996)

“For what? A little bit of money.” The conclusion of the dark morality play Fargo shows the true north of Marge Gunderson, a woman who is not oblivious or naïve to the darkness of the world, but ultimately is too good of a person to fully understand what would drive one person to put another into a woodchipper. And yet even faced with that kind of darkness, she doesn’t let it twist or corrupt her. Instead, she settles in to bed with her husband, they reassure each other, and find peace in their simple lives. It’s lovely. – Matt Goldberg

The Godfather (1972)

The completion of Michael Corleone’s journey is almost bittersweet. He starts out believing he will be different from his family, and he discovers that he’s the one best suited to lead their dark legacy. Every attempt he makes to get away, he only finds that he’s in deeper and more adept as being a mob boss. So it’s particularly chilling when he becomes “The Godfather”, lies to Kay with a straight face, and then, in a powerful shot, the door between them closes, Michael living a life of crime with one family, and his actual family on the other. – Matt Goldberg

The Mist (2007)

Frank Darabont’s The Mist is a rousing, tightly crafted parable by way of B-movie creature feature that updates Stephen King’s 1980s novella and plants the action firmly in America’s post-9/11 culture of fear, rage, and blind panic. Darabont once described the film as a “wounded, angry cry” and never is that more clear than in the film’s final moments, which have earned a spot of infamy as one of the most blistering, brutal film endings of all time. King’s novella ends, quite literally, with hope; Darabont’s film ends at the soul-crushing defeat of giving up hope. It’s the anti-Shawshank Redemption. King himself described it as “the most shocking ending ever” and said “there should be a law passed stating that anybody who reveals the last five minutes of this film should be hung from their neck until dead." So uh, no spoilers for this one, even ten years later. — Haleigh Foutch

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

Nominated for 11 Academy Awards upon its release in 1950, Sunset Boulevard has the distinction of standing the test of time as a classic film that still holds up incredibly well today. Moreover, while audience tastes and trends have evolved, the ending to Billy Wilder’s film noir remains tremendously effective—it’s the epitome of evergreen. This story of an unsuccessful screenwriter who gets drawn into the secluded home of a forgotten silent film star is packed with tension and heightened emotion, but Wilder tells the audience up front you’re not in for a happy ending—the film begins with our protagonist lying dead in a pool. By the film’s end we empathize with poor Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) even as she commits murder, rendering her final line ”All right, Mr. Demille, I’m ready for my close-up,” not one of delusion or insanity, but tragedy. – Adam Chitwood

Almost Famous (2000)

If Cameron Crowe never made a great film after Almost Famous, he’d still be considered one of the greats. That's how good Almost Famous is. His 2000 semi-autobiographical comedy-drama is a genuine masterstroke, chronicling the exploits of a teenage journalist on the road with a rock band in the 1970s. It covers all your traditional coming-of-age tropes like young love, sex, and insecurity, albeit against the backdrop of superstardom, fame, and ego. It’s this perfect concoction that comes to a tremendous close in William’s (Patrick Fugit) bedroom, where he’s visited by Stillwater standout Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup) to finally complete that interview he’s been promising. The two have a heart-to-heart that miraculously avoids the saccharine and instead comes off as intimate, while we also get a peek of Penny Lane making her way to Morocco. “To begin with, everything.” – Adam Chitwood

The Act of Killing (2012)

The Act of Killing is a wildly difficult film to watch and a genuinely perspective-augmenting piece of filmmaking. That might sound dramatic, but this unconventional documentary tackles genocide and human cruelty in a way that rips down the walls of defensiveness we’ve built to the horrors of the world, and makes them feel fresher and more horrifying than ever. Even to the men who committed them.

To make The Act of Killing, filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer spent years alongside the men responsible for untold violence and death during the Indonesian genocide. Oppenheimer side-steps standard documentary format by having these men recreate their crimes on camera, through their perspective, offering a searing look at the deluded and appalling thought processes of these casual killers. They laugh and brag about their crimes, relishing in the details of their memories, until the film’s final scene, which sees one of these men finally confront the magnitude of his crimes. He gags and shudders, retching on the rooftop where he once callously executed innocent men. “Have I sinned?” he asks as his body contorts and heaves. It’s a shocking moment of empathy from a monster and empathy for a monster that brings the full weight of inhuman cruelty crashing down on you. — Haleigh Foutch

All That Jazz (1979)

The “tortured artist” has become a Hollywood cliché, but what happens when the tortured artist makes an incredibly self-aware autobiographical biopic? That’s Bob Fosse’s musical masterpiece All That Jazz, which lays out the good, the bad, and the ugly of the filmmaker, writer, and choreographer’s life via Roy Scheider. As the film comes to a close with Scheider’s protagonist on his death bed, the five stages of grief present themselves as a grand musical finale featuring figures from all throughout his life. It’s at once incredibly egotistical, apologetic, gregarious, and beautiful, and it wraps up in a stark closing shot that brings us crashing down to reality. It’s truly unforgettable, and one of the greatest “grand finales” of all time. – Adam Chitwood

The Graduate (1967)

I adore this ending. The head fake is that Benjamin and Elaine will run off together and live happily ever, but director Mike Nichols cleverly brings it back to where the film started: Benjamin being carried along, wondering if his life will have any meaning or even be different than what his parents had. Letting The Graduate just sit with these two characters as their impulsiveness leaks away and they’re forced to just sit with their choice is a powerhouse of an ending that never needs to raise its voice. – Matt Goldberg