I remember our first conversation [about Birdman]. You called me and said, ‘Chivo, I have this idea. I want to do this movie and I think I want to do it in one shot but I'm not sure if it's possible…’ At that moment, my brain switched off and I was only thinking [one thing]: please don’t let him offer me this job.

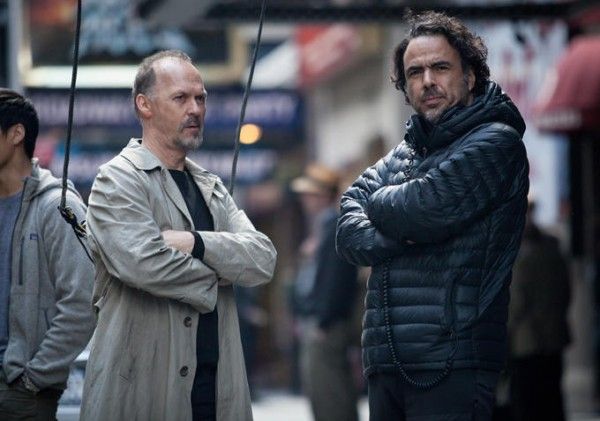

Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (often referred to as ‘Chivo’) and filmmaker Alejandro González Iñárritu go way back. The two worked together on some of Iñárritu’s earliest broadcast commercials in Mexico. “He told me he wanted [the commercial] to be shot like The Godfather”, Lubezki reminisces about their earliest collaboration. What, pray tell, was the commercial in question? “Oh… A Father’s Day ad”, Iñárritu confides with a wry smile.

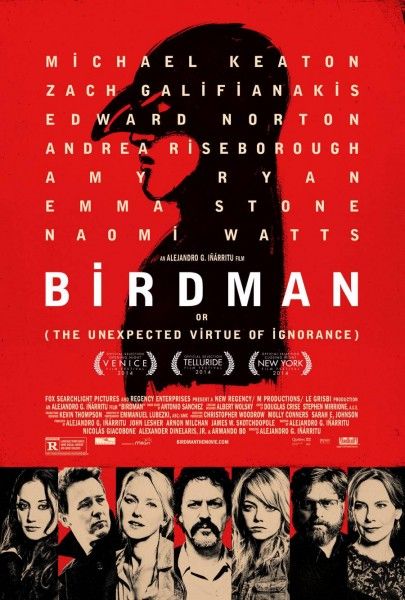

The two have known each other for so long (working together since the Father’s Day ad on a couple shorts and a big time Nike commercial) – it might come as a surprise to learn that Birdman marks the duo’s first feature collaboration. They don’t disappoint.

The one shot (or long take) is an oft-used gambit in filmmaking. Hitchcock, Warhol, Figgis, among many others have all utilized the shoot-the entire-film-in one-continuous-take; but never has it seemed as seamless as it does in Birdman. Recently at this year’s AFI Film Fest, I saw an Iranian film titled Fish & Cat – which also utilized the one-shot technique. It’s an interesting experimental film – the way it employs the one shot to intermingle fantasy & reality, the past and present all continuously within the same moment more than makes it worth tracking down – but boy-oh-boy does the movie drag on and on, too much time spent following one person as he walks for ten minutes to some location so the film can continue on to the next scene. You can’t help but think the picture would benefit from a cut or two. The great thing about Birdman is the simple fact that that thought never once crosses your mind. The one continuous shot never feels like a limitation. It never feels like Lubezki or Iñárritu are stretching to make the movie work within the confines of one take; in fact the opposite is true: Birdman works because it is one-shot. The lingering continuous camerawork adds a dream-like quality to the picture that serves as foreshadowing to the more surreal and harder-to-explain third-act.

This week, the Landmark Theater held a retrospective on the works of Iñárritu, culminating on Saturday with a screening of Birdman and a post-feature interview with Iñárritu & Lubezki. There’s a nice easy-going camaraderie between duo. They seem to genuinely enjoy each others company and are more than willing to poke gentle fun at each other, more often than not at Iñárritu’s own expense. The result is a fairly loose conversation: mostly focusing on Birdman’s one shot – its conception and meaning and why they broke away from the ‘oner’ for the beginning and end of the feature. Below are highlights from the exchange.

On the Conception of Birdman’s One Shot:

IÑÁRRITU: [The one shot] was conceived the moment I knew the movie was about the ego. I knew that it has to be told optically. It has to be a more subjective experience. Not just observing the character but living through his mind… To really not only understand and observe, but to feel, we have to be inside him. [The one shot] was the only way to do that.

LUBEZKI: [To be honest] I was very worried. I wasn't sure you could tell the story [in one shot]. I understood the importance of doing it that way in terms of how to express the emotions of the character and to get the audience immersed in the movie and so forth. But I knew it was going to be incredibly hard. It takes an absolutely insane person like Alejandro to take a whole crew... No, no -- he's completely insane... It's naive, irresponsible, crazy...

IÑÁRRITU: He’s my friend by the way…

LUBEZKI: But that's what makes an artist an artist. I would have never gone through it. And many days I would go up to Alejandro and say 'Please, let's just cut one more time. Why do you want to go through all of this?' And you need somebody with the courage and the strength and curiosity to take all the crew and production and studio and all the actors that way. It's a really courageous... and irresponsible thing to do.

IÑÁRRITU: …We are trapped in continuous time. It’s going only in one direction. That's why we get old and die. [It’s why] we can't go back to our youth and visit two hundred years before. Fiction, film and every art in a way is a means to get out of our dimensional existence to time. That's why we love it. We are imagining different realities because we can’t escape our own. This continuous shot… has a [different] emotional affect. You get an experience closer to what our real lives are like.

On Breaking Away from the One Shot for the Opening/Closing Falling Comet Shot(s):

IÑÁRRITU: Honestly that came as we were shooting. I always say: you plan for years germinating an idea; but you attract more ideas when you are actively doing it. A concept when it begins to take shape and enter existence, it begins to attract different things you didn't expect. The movie needed something to imply… something. What -- I didn't know. It’s one of those unconscious things and I saw some images of comets and I began to understand something that I was feeling but was not able to articulate in the script. When I saw that comet, [I thought] it was a way for me to say, without actually saying, the state of mind of this character [Riggan] -- he was a guy on fire, he was inspired, he felt that he was flying as a superhero, that he was a star. But the most interesting thing for me was when I discovered the dead jellyfish part -- that's exactly who this guy is. He's a guy who for one hour feels like a comet on fire and thirty minutes later he feels like a dead jellyfish.

LUBEZKI: I remember when Alejandro found that image of the comet. We were trying to [figure out] how do we integrate it into the movie. Is it valid to cut and chop the movie if we were trying to do this one shot? We got to the conclusion that it was actually better to have these cuts and not try to do an Olympic one shot just to show off.

On the Ambiguity of Birdman’s Ending:

LUBEZKI: I love in Alejandro's work the ambiguity of all these images. It's so funny because in America all these people get so upset. Why is it not explained? What does the ending mean? I can't tell you how many people come up to me and ask is he dead or isn't he? I just love these images that are poetic. It's an approach to storytelling that makes you feel. I feel that's more important than explaining or being too literal of certain things.

On Cinema Today:

LUBEZKI: Film is an industry and it has to keep producing and moving. It's easier to make everything in parts and do it fast. You need people like Alejandro, within the industry and all the limitations, to try to manufacture something else... Within this factory, you can still find a language that is slightly different and pulls an audience into a movie in a different way.

IÑÁRRITU: We are so used to being comfortably taken to different places. We can see war and people dying but we're in the comfort of our own seats and we can separate from fiction… Cinema has been relying comfortably on a very artificial way to make everybody entertained. We have stopped exploring possibilities... because nobody pays attention. Everything is about the story or the good edit. The commodity of it all -- if it's entertaining. When you see a review or a critic talking about visual grammar, they don't even know what that is.

A couple hours after this interview, Iñárritu would win the DGA Award for Best Director, all but cementing Birdman as the front-runner for this month’s Academy Awards. Birdman is currently still playing in select theaters. Next Tuesday, it hits Blu-ray and DVD – just as Oscar voting ends.