Todd Haynes has built a career in bold cinema. He began his directorial career with an experimental documentary film that used Barbie dolls to re-enact the eating disorder and depression battles of Karen Carpenter, and then used PBS' money to film a delirious short film about a young boy who desperately wants to be spanked after seeing it happen to a TV actress named Dottie. He jumped into indie prominence with a chemical paranoia tale in Safe, then went straight to the glam-rock bisexual opus of Velvet Goldmine. Then Haynes followed up his biggest mainstream acceptance, the Douglas Sirk-inspired 50s melodrama update Far from Heaven—which included the sexual orientations and racial imbalance that Sirk could only allude to—with an unconventional biopic of Bob Dylan—played by both genders and multiple actors—in, I'm Not There.

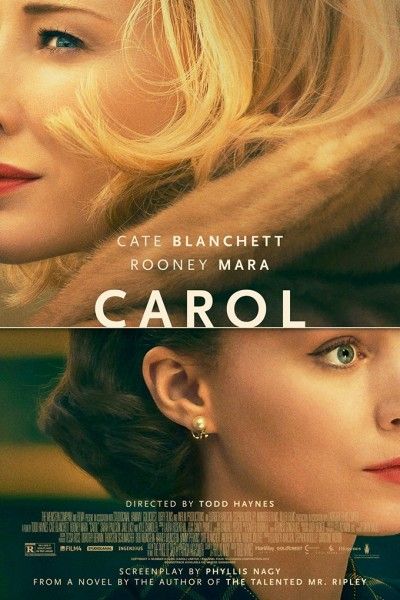

Carol is Haynes' newest film after a long hiatus—a hiatus that also included the magnificent HBO mini-series Mildred Pierce—and though it might be his most straight-forward movie, it is deceptively bold. More simply put, Carol might be his most grand film. This is Haynes at his most formal. Carol is focused on gestures, and requires patience—something that falling in love also requires—but pays off immensely as one of the most aching, heartfelt, and expertly performed films of the year.

In a 1950s department store, Therese (Rooney Mara) is stuck working behind the doll counter. Though it's not in her section, she sets up the Christmas train set in a different area of the store before it opens, and then resigns herself to her post. In a sea of housewives frantically shopping for the right doll for their daughters, Therese notices a striking woman in a full-length fur coat take her time moving about the store and stop to turn on the train set. Therese is jolted by the gesture, as if the little switch to make the train go is wired in her own muscles. The woman is Carol (Cate Blanchett). Carol can read Therese's intrigue and either leaves her leather gloves on the counter on purpose, or she forgets them because she's so curious about the young woman who's caught her eye.

The entire transaction of buying a train set is packed full of information. Instead of purchasing from the proper department, Carol buys it from Therese, wanting it shipped to her home and providing an address and telephone number. Therese returns the gloves through the mail, and checks on the status of Carol's order. Grateful for the gloves being returned, lunch is requested by Carol, who then uses lunch to request a Sunday social with Therese. These Sundays become routine, and both of their lives are impacted by the things left unsaid during these routine Sundays.

Carol is beginning a divorce from her husband, Harge (Kyle Chandler). Harge still wants to be with Carol, and just when Carol thinks she's finally moving into her desired lifestyle, Harge uses her long ago affair with their daughter's godmother (whom Carol refers to as her daughter's "aunt"), Abby (Sarah Paulson), against her in the divorce proceedings—citing a morality clause that should keep their daughter away from her (unless she comes back, of course). On the opposite side of tangled relationships is Therese, who is still tangled though, as she is marginally dating a man at the store (Jake Lacey) who doesn't push her into intimacy, but is attempting to push her into marriage.

Haynes truly understands that when falling in love it's the things that go unsaid, but are said with glances and hand placement that not only speak the loudest, but get the most attention as you're trying to piece together your feelings. For two women who are falling in love in the 1950s—one with some experience and the other without—these glances, head tilts, and gentle touches of reassurances have to speak even louder because acting upon it impulsively could have consequences.

Narratively, Haynes (and screenwriter Phyllis Nagy) are careful in not only building tension, but in building awareness that Therese and Carol are having two entirely different experiences, one of finally moving into living as who she is, the other not sure of who she is at all; they are meeting at the same time, and attracted to one's assuredness, and the other's uneasiness. The film is based on the novel, The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith, who was famous for writing numerous stories involving Tom Ripley, a.k.a. The Talented Mr. Ripley. This story might seem like an outlier for the author, but there are some detective qualities. Carol is about people trying to figure one another out and people who are watching each other so closely it veers on spying.

But Carol isn't just Therese and Carol trying to figure each other out—unable to ask the questions they want to ask; no, men are also trying to figure out Carol and Therese. In a beautifully framed shot, Harge goes to Abby (with whom Carol is still very close friends) to ask where she is and declare that he loves her—as if it has to be returned. In one swift motion, Abby shuts the door on him, and Harge remains, gazing through the glass square on the front door, still wanting answers. Therese not only has a boyfriend who begins to realize that Therese is making a "mistake", but there's also his friend, Dannie (John Magaro) who's interested in her. Dannie works at the New York Times and has seen Sunset Boulevard six times, appropriately noting that he keeps watching it to see all the things that they mean but aren't saying, and hear all that the things that they're saying but not doing.

The Sunset Boulevard reference isn't just appropriate for Dannie's takeaway line that greatly informs Carol. Billy Wilder's film concerns an older woman who lives alone, and is seeking companionship, relevancy, and acknowledgement that she's worth something. And it features a towering performance from Gloria Swanson—with great lines. Haynes obviously adores this era of cinema, and he gives Blanchett lots of classic lines that would fit in perfectly within that era (choice examples: "Just when you thought it couldn't get any worse, you're out of cigarettes." "Do you think you can handle a redhead?"). Blanchett relishes these lines, but also shows immense restraint and calculation in her seduction, and an obvious love for her daughter, the only part of her previous life she still wants.

But, though titled Carol, this is Therese's film. And Mara absolutely astounds. Therese does not know who she is, but Carol (and even Dannie) is an instrument who helps put her on a path to find herself. Therese vacillates between having a crush and being crushed, and Mara uses her eyes to speak for her with glances, with tears, and by being hidden behind her camera lens. On a road trip they take together, expert costume designer Sandy Powell dresses Therese in slightly oversized dresses that make her look much smaller, like she would be entirely unable to take control, or that she's still childlike. Carol's rupture on potentially losing her daughter for being true to herself is heartbreaking, but it's Therese's attempts to make Carol's now-conscious decision—so much earlier in life—that makes you hope and ache.

Carol is the most romantic movie of the year, and through Mara's performance—and Haynes' careful direction—it might also be the most cathartic.

Grade: A

'Carol' made its North American premiere at the Telluride Film Festival on September 4th; it will be released in theaters on November 20th.

Click here for all of our Telluride 2015 coverage. Click on the links below for our other reviews and diary round-ups: