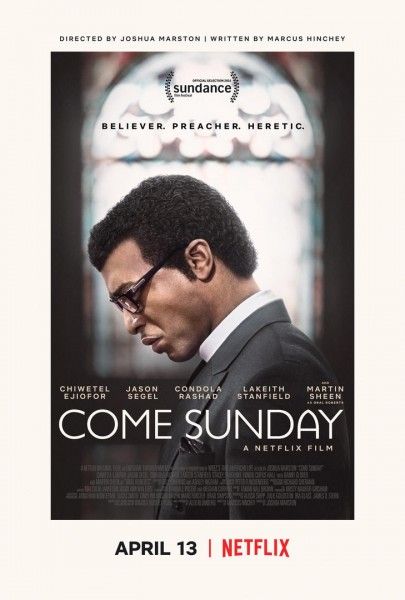

[This is a re-post of my Come Sunday review from the 2017 Sundance Film Festival. The film is now available to stream exclusively on Netflix.]

Full disclosure: I was born and raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the setting of the true-life drama Come Sunday. So I can say with full confidence that when Bishop Carlton Pearson, the leader of a wildly popular Pentecostal church, preaches one day that there is no Hell and humans don’t have to be saved by Jesus to get into Heaven, it was definitely met with strong reactions from not only his congregation but the evangelical-leaning community of Tulsa at large. Director Joshua Marston’s fictionalization of Pearson’s epiphany is certainly an intriguing story, and Chiwetel Ejiofor delivers an unsurprisingly terrific performance as Pearson, but even though it’s told well, this particular tale struggles to fill out the runtime of a feature-length film.

In the late 1990s, Bishop Carlton Pearson had an epiphany. While he was the leader of the extremely popular Higher Dimensions church in Tulsa, where his sermons were broadcast on television, he encountered a couple of events that forever changed his outlook on preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ. One, his incarcerated uncle (played by Danny Glover) hung himself after Pearson refused to write a letter to the parole board, instead insisting that his uncle wasn’t ready to be saved just yet and needed to “do the work.” According to the Gospel he preached, his unsaved uncle was now in Hell. Additionally, Pearson was troubled by the Rwandan genocide, in which thousands of innocent people—including children—were killed. Having not been saved, again according to the Gospel he preached, all of these people were now in Hell.

After watching footage from Rwanda one night, Pearson is visibly distraught and prays to God for guidance. It’s then that, according to Pearson, God spoke to him and told him that there is no Hell. Those killed in Africa did not need to be saved to enter the kingdom of Heaven, and thus everyone on Earth could still go to Heaven even if they don’t make the explicit decision to accept Jesus Christ as their savior.

Pearson decides to speak about his conversation with God during his next sermon, and as you might expect, his congregation, colleagues, peers, and mentors are extremely troubled. He’s pressured to recant his testimony, and Oral Roberts himself (played by Martin Sheen)—Pearson’s mentor—suggests Pearson may not have heard God that night, but the Devil instead. But Pearson persists, even as his congregation crumbles apart and longheld friendships come to an end.

This is certainly an interesting story, and indeed Marcus Hinchy’s script for Come Sunday is based on an episode of This American Life, but throughout the film it’s hard not to think the story makes a better episode of that program than a feature film. Marston directs the film with care, and the performances by Ejiofor and standout Lakeith Stanfield—as Pearson’s closeted choir leader—are pretty outstanding, but as the film moves along it starts to run out of steam. Things just kind of happen, and while some may get more mileage out of Pearson’s crisis of faith than others, once he makes his proclamation we’re left with what’s essentially a two-act denouement.

The film is, however, refreshingly un-hagiographic, as it does dig a bit into Pearson’s pride and arrogance that may have led some to question his testimony. But it feels as though if the script had focused on this aspect of Pearson’s character a bit more, we might have gotten something more dynamic and complex. As is, while the film doesn’t portray Pearson as a saint, it portrays him as a fairly uncomplicated character, all things considered.

But the film is also refreshing in that it also doesn’t paint Pearson’s doubters as evil or antagonistic. Martin Sheen portrays Oral Roberts, and while the film could have gone down the Bible thumping route, instead it takes time to let us consider and understand Roberts’ position as a lifelong and devout evangelical Christian. The same can be said of Jason Segel’s business manager Henry, who built Higher Dimensions alongside Pearson but who can’t stand by Pearson's new Gospel of Inclusion. We see he doesn’t resent Pearson, and instead is heartbroken to see what he believes is his friend’s own path to Hell. The film also takes time to consider the thoughts and beliefs of Pearson's wife Gina (Condola Rashad) instead of simply relegating her to concerned/adoring housewife, which is a nice change of pace.

There are interesting ideas in Come Sunday to be sure. Ejiofor’s performance is human and empathetic, and Lakeith Stanfield once again nearly steals an entire movie with a stellar supporting performance. And those fascinated by crises of faith or stories about religion will find stuff to chew on, but as a feature film it leaves something to be desired.

Rating: C