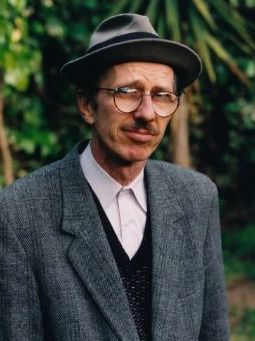

Robert Crumb starts the documentary Crumb by describing the works he’s most famous for, the first being the slogan “Keep on Truckin’” which he doesn’t understand why it caught on and it got him in trouble with the IRS. The second is an album cover he was paid $600 to design, says was stolen from him, and then he notes the original artwork sold for $21,000. The third is “Fritz the Cat,” which was taken away from him and turned into an animated feature, and he so despised what they did to the character that Crumb killed him in a later comic strip. This also sets up one of the initial premises of Terry Zwigof’s documentary: if you think you know Crumb, you’re probably wrong. My review of The Criterion Collection’s release of Crumb on Blu-ray follows after the jump.

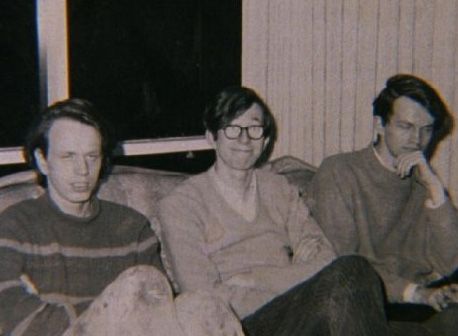

Besides his resolutely anti-sellout aesthetic, the film offers three core elements. The first is biography, which essays how Robert grew up, his family, and what inspired him to become – and probably still is – the most famous and renowned underground comic book artist, the second is a dissection of his more controversial elements, especially his sexual predilections, and third is a chart of his two brothers - Charles and Maxon - and the paths they took as adults. The bio-pic elements are the backbone, as the film goes up to the point that Robert leaves the country for a life in France, while it also highlights his tumultuous relationship with his family and the women in his life.

This ties into the sexuality. Crumb states pretty flatly that when he was a teenager he though the route to go was to be sensitive because women were always complaining about the tough kids, but were always attracted to them. Of course – as he says – that all changed when he got famous. The film then dives into his fetishes, and he’s noted to be a foot fetishist (and he talks about this a bit in graphic detail), his love of piggyback rides, his predilection for larger, stronger women, and the artwork that explores his perverted side. One such piece has a man sodomizing a headless woman, and there’s other similarly-themed, sexually explicit text. A lot of this comes at the beginning of the film.

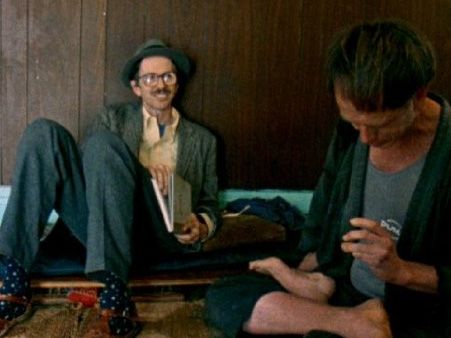

The genius of the film is that it contrasts this with his brothers. They too suffered under an abusive father, were generally wimpy, and abused at home and at school, and it was at home where Charles forced his brothers to draw comic books. All three brothers are obviously damaged, but Charles’s solution to his problems is to hide away, as he lives with his mother and rarely leaves the house. Maxon left home, but lives in a crappy apartment, does his art, and spends his days begging for money on the streets, having gotten into some trouble with sexual assault (mostly pulling down women’s dresses). For Robert, he gets the release from his art and his success, and so by the end of the film - even after being confronted with the worst aspects of him - the film builds a respect for an uncompromising artist, who has used his personal demons to create something of value.

And in that Crumb achieves what few films about artists are capable of, it gives you a full portrait that doesn’t gloss away from some of his worst sides to show where that art partly comes from, but also that for some creating is the only way to stay sane, to understand one’s self. Even if you walk away from the film not liking the person, you respect the journey and what he stands for.

With the passage of time (the film was released in 1995), it’s interesting to note that the film was made as the cultural significance of integrity and of authenticity was starting to fade from pop culture. This has a lot to do with how pop culture has changed, but for college radio rockers and people like Nirvana, etc. there was always a sense and a talk of not selling out – even if you were already a part of the cultural conversation. Crumb did not sell out; nowadays there’s a sense that to even make a blip on the radar you have to compromise.

The Criterion Collection’s Blu-ray is going to look as good as it ever could. The film was shot in the academy ratio (1.33:1) and in 2.0 monoaural sound. The picture looks better than previous releases, but it suffers some grain. The film originally shot on 16mm, so there’s only so much 1080p of resolution can do to make it look better. The film comes with two commentaries, the first with Roger Ebert and director Terry Zwigoff from the 2006 special edition, while the second is one Zwigoff recorded solo in 2010. Both are insightful, though Zwigoff misses having someone to fall back on, and there are a number of repeated anecdotes. There are fourteen sequences labeled “unused footage” (52 min.) with very sporadic optional commentary. These are mostly completed thoughts that add to the film, but you can see why Zwigoff paired the film down to a two hour running time. There’s a small still gallery, an excellent booklet, and a copy of the “Famous Artist Talent Test” that Charles Crumb took.