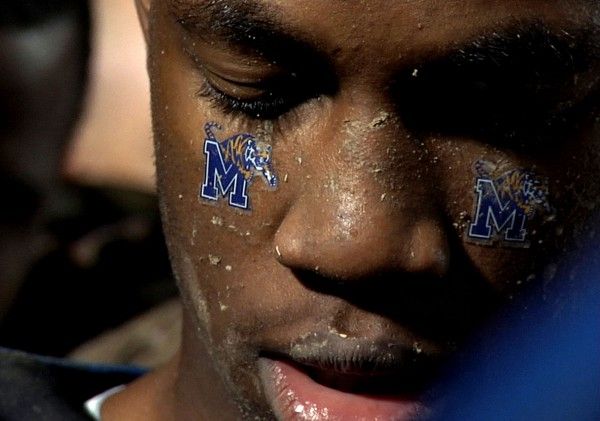

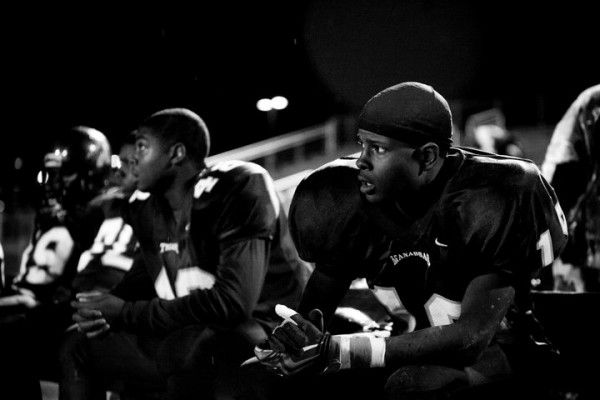

From directors Dan Lindsay and T.J. Martin, the Oscar-nominated documentary Undefeated (opening in theaters on February 17th) is set against the backdrop of a high school football season at Manassas High School in North Memphis. Chronicling three underprivileged student athletes (O.C., Money and Chavis), along with their volunteer coach, Bill Courtney, the film shows the Tigers as they find their footing and their confidence, and finally attempt to break the 110-year-old play-off jinx for the school.

At the film’s press day, filmmakers Dan Lindsay and T.J. Martin talked about spending time in North Memphis to gain the trust of the players and community, going through the 500 hours of footage they shot in order to make the documentary, what led them to the three student athletes that they ended up building the narrative around, how worried they were that all of the material would not come together in a cohesive way, and what they hope audiences will take away from this film. Check out what they had to say after the jump.

Question: Having spent three years of your life on this film, what is this whole award season experience like for you?

Dan Lindsay: Yesterday was the first time I was like, “Oh, this actually happened. This is real. We’re actually nominated.” I can’t thinking that somebody was going to say, “Oh, we screwed up. We’ve gotta take your invitations away.” It really sunk in when they did the whole presentation about how to give a good acceptance speech [at the Oscar luncheon].

T.J. Martin: That was the moment it sunk in for me, for sure. We got picked up by The Weinstein Company last March at South by Southwest, and that was like, “We’ve done it! That’s amazing! Other people will actually see this movie, aside from ourselves!” And then, it made the short list and I was like, “Oh, I just pissed my pants! That’s crazy!” The Toronto Film Festival was amazing.

Lindsay: That was the life goal. I couldn’t believe that happened.

Martin: And then, we got nominated. At first, I just thought the publicist at The Weinstein Company, who called screaming into the phone at 5:30 in the morning, was playing a really bad, cruel joke.

Lindsay: For us, to get nominated is amazing, but it’s way more a testament to the people that we made the film about. The fact that the players on the team and Bill [Courtney] and the people in the community trusted us, in the way that they did, to give us the emotional candor that we were able to capture in the film, we wouldn’t have a film without that. Obviously, those were the first people that we called and said, “You’re not going to believe this!” I called Chavis, one of the players, and said, “We got nominated for an Oscar!,” and he said, “Yeah! What’s next?” I was like, “That’s it! That pretty much as big as it gets.”

How long were you actually shooting this for?

Lindsay: We lived in Memphis for nine months, and we shot intensely for about four or five months. The last three and a half months we were there, we were beginning to watch the footage. We shot 500 hours of footage to make the film, so it took us over three months just to watch it all, and that was dividing it in half and each watching 250 hours. And then, when we started cutting the film, he cut the footage that I watched and I cut the footage that he watched. That was the way we were able to succinctly, relatively speaking, view all the footage. Even in those last three months when we were there, we’d go, “Oh, we need some more shots of North Memphis,” or “Man, we don’t have a good exterior shot of the school at night.” We’d go and pick up some of that stuff.

Martin: We started going through our storylines, just to see if there were any holes in the story, so we could do a quick interview just to contextualize certain things, here and there.

Did you know early on that Chavis, Money and O.C. were the three guys that you were going to focus on?

Lindsay: O.C. was actually how we found the story. There was an article written about him in the Memphis Commercial Appeal that Rich [Middlemas], our producer, found and sent to us. It’s mentioned in the film, but it was about O.C. living in these two disparate worlds. Rich sent it to us and said, “What do you think of this as a documentary?” We thought it was an interesting world, enough to at least go there. At that point, we thought it would be really interesting to do a coming of age story of his senior year. Going there was when we met Bill [Courtney], the coach, and we thought he was interesting. Once Bill told us the history of the school and the team, that was when we changed focus and decided to make it more about the season, but still as this intimate coming of age story. We met

Money on the first trip there. Even when we thought it was just going to be about O.C., we wanted another player to juxtapose his experience. It was like, “Who was the guy on the team who didn’t have the same athletic prowess and maybe needed help in another way? Maybe he’s not getting the same amount of attention.” We met Money when he was waiting for Bill in the weight room. He was the only player on time, waiting there for Bill, and we were like, “Okay, who’s this guy?” And then, Chavis became a character just as a result of being Chavis. He’s a juggernaut of drama, or at least he was that season. His actions were affecting the team in a way that drew the camera to him.

Martin: There was one other character that we followed all the way through [that we ended up cutting out]. The kids that we profiled in the film also are representing a lot of other stories on the team, and in North Memphis. Specifically, we followed those characters because we went into it knowing that we wanted to make something that was very cinematic and played out more like a narrative. We really wanted people to forget that they were watching a documentary. So, it was important for us to have characters that actually interacted with each other, or had an affect on the team, which affected the greater trajectory of the story. We followed another player who had a really compelling storyline. He had just turned 18, at the beginning of the year, and had just gotten kicked out of the foster system, but he still wanted to finish his senior year, so one of the volunteer coaches actually took him in, in what ended up being his 19th foster home in the past four years. It was really compelling material, but for us, we wanted the sum to be greater than the parts. I feel like a lot of documentaries have this one storyline, but then just have these vignettes. We really wanted it to be one cohesive, strong, narrative feel, so that’s why we stuck with those storylines, in particular.

Lindsay: In a rough cut, it felt like you were veering off, when we went to his scenes.

Did anything have to be re-enacted, or was all of this as it was happening?

Lindsay: It was as it was happening. A lot of the stuff we filmed after never even ended up in the film. We’d be like, “Oh, let’s get somebody to contextualize this, in case we need it later.” Our process going into it was to move there for the purpose of being around for everything. We’re interested in making documentaries that are experiential, where things are unfolding in front of the camera, and they’re not anecdotal or talking head pieces where they’re discussing a subject. We want to see it happen, so the only way to do that was to be there for everything. We went to practice, every day. We went to school, every day. That’s why we had so many hours of footage.

Martin: We would also shoot talent shows, knowing that they would never end up in the film, but we really wanted to earn the trust of, not just the team and the coaches, but the community, as a whole. We felt that, at least in North Memphis and community similar to that, more times than not, when there’s a media presence there, they want to do a sensationalized piece about how violent the neighborhood is, or something like that. We came in, as an outside entity, saying, “We want to tell your story.” So, in order to gain that trust, we had to commit to that and show up, every single day. We had to earn their trust, and then put ourselves in a position to actually capture things that unfolded in front of the camera, so we didn’t have to have a talking head tell you anecdotal things that happened in the past.

Were you ever worried that all of this material wouldn’t come together in a cohesive narrative, at the end?

Lindsay: Yeah, of course!

Martin: Every day!

Lindsay: If they had lost every game, we would have made a movie about a team losing every game. The story reveals itself to you, at least in this process. The story tells us what it’s going to be. This is what happened. We actually didn’t want to make a sports film, going into it. Granted, we were going through a football lens, but we thought maybe it would veer into something more about education. But, after a few weeks, we couldn’t deny that the drama was happening on the field and revolved around the team. That was the story that was telling us it was going to be.

Martin: With that said, even though it’s a “sports film,” the themes that are explored in the film are much more universal. You could replace football with chess, painting or soccer. Generally speaking, the way we work is that the themes will present themselves to us, and then we’ll decide what we really want to explore within the narrative while we’re shaping the film, and we just stick to that. In this case, it was fatherhood, resilience, and taking advantage of opportunity or a lack thereof.

Was there anything you had to cut for time, that you wish you could have left in?

Lindsay: That’s a difficult question because there were moments when I watched and went, “That is amazing,” but it didn’t fit in the narrative of the story that we ultimately ended up telling. There were speeches by Bill [Courtney] that are incredible. It was really, really moving stuff.

Martin: There wasn’t anything that we specifically cut for time. If it felt like it was veering off from the spine we had created for the trajectory of the story, then it didn’t belong there.

As documentarians, do you have to try not to get too close to your subject, or is that what you’re going for, in order to tell the story?

Lindsay: People have different approaches. There are probably some filmmakers who would say that you can get too close, and I definitely think that you can. But, for us, that’s something we don’t shy away from because with documentaries, what you’re watching is really the relationship between the filmmakers and the subjects. It’s almost impossible not to get involved. But, you still have to be conscious of the fact that you are getting involved. We’re very careful about how much we reveal about ourselves to them. You reveal as much as necessary, as you’re having a conversation. You’re not hiding anything, but as part of the process, you also want them to believe you could be anything. You don’t want them to judge themselves for what they’re saying.

Martin: It’s a weird balance between wanting your subjects to be comfortable enough, so you do become a friend of sorts, but at the same time, it’s definitely not a reciprocal relationship. You are doing a lot of consuming and taking. You just have to make sure that you maintain a balance where you keep the relationship open for them to continue to be who they are.

Lindsay: We were very clear, at the beginning. I remember having a long conversation with Bill [Courtney], when we barely even knew him, and I was like, “Look, by the end of this, we probably will be friends. We will become very close with each other and this will be a very intense experience, and then we’re going to leave and our lives will go on.” That’s a really strange thing, so you try to talk to people about it beforehand, so they’re aware of that and they’re comfortable with the idea of that. But, I think the approach of how close you get is seen on screen. If you’re really surgical about it and just hands-off and it’s almost sterile, I think that shows on screen. When you get really close with your subjects, and sometimes too close, where you can tell that somebody is keeping a moment in or they’re editing themselves, you can see their relationship in a way that’s not good. I think that gets revealed on screen. It’s the level of intimacy you have to watch, so that it can play out on screen successfully.

Martin: This is not objective journalism. Once we noticed how emotionally candid people were with us, and we captured all that material, we had an emotional experience, over the course of making it, and it was about imparting that experience to a greater audience. If we did that through what we felt was emotionally what we went through, over the course of making the film, then that was a success to us.

Lindsay: We wanted an audience to care as much for Money, when he finds the news out about college, as it did to us. I was shooting that and bawling. He goes out of focus when he’s walking away because I couldn’t get my arm up to focus the camera. It was just so huge, and our job was to get the audience to the moment where they felt the same thing that we felt about that.

What did Coach Bill Courtney think of the finished film?

Lindsay: He said he sees a really fat red-haired guy, and he needs to lose some weight. That’s what he told me. We showed him a rough cut, before South by Southwest. He said, “The only way I can do this is if we have a gentleman’s agreement that I can watch the close to final cut, so that I can pull out things that I’m uncomfortable with.” I said, “Well, we can never do that. We can’t make that agreement with you. But, we’ll show it to you and, if there’s anything in there that you feel is inappropriate or that you wouldn’t want people to see, and we can’t tell you why it has to be in there, then we’ll take it out ‘cause then we’re just being provocative for provocative’s sake.” We showed it to him at his office and I turned around to see how he was, and he was just a mess of tears. It took him a second to collect his thoughts, and he was like, “It’s been a year for me since I have not been at Manassas. You have to understand that that was just such an emotional, powerful time in my life, and to relive it like that was just overwhelming for me.” Then he said, “Now, play it again ‘cause I couldn’t pay attention to the first half hour because I kept thinking about how fat I looked.”

What was the biggest struggle or challenge in making this film?

Martin: The biggest challenge has been since the film has been finished. The biggest challenge for me is getting people to watch the film. We have this joke that, if I was at a film festival and I saw the description of our film that said, “Inner city high school football team overcomes the odds,” I’d be like, “I’ve heard it before. I’ve seen it before. I’ll let someone else see it and tell me how it is.” That was the biggest struggle, even just socially. On paper and in conversation, it sounds kind of trite, or like something you’ve already seen. But, it’s like, “No, it’s so much more than that. It’s like Hoop Dreams, but not really like Hoop Dreams.”

What do you want audiences to take away from this film?

Martin: That’s different for everybody. For myself, what I took away from my own personal experience was definitely to appreciate and value the opportunities that I’ve had in my own life. We never set out to make an issues-based film, or to have a certain agenda or message. With that said, we also didn’t shy away from the realities of the obstacles that that community faces, and the class and racial dynamics. At the very least, in the process of telling a human interest story, if people actually invest emotionally into the lives of these students and see the obstacles they face, hopefully it will illicit and inspire a greater conversation about race and class, and some of those social issues. That’s one thing I hope people take away with them.

Lindsay: For us, we’re not particularly interested in making advocacy films that say, “You have to believe this.” I don’t have a personality where I think I can tell somebody what they need to think. It’s more about storytelling. I would want somebody to get swept away in the experience, and take from it what they take from it. We purposefully put sub-textural themes in the film and try to make every scene speak to those, so that you are thinking about those, either consciously or subconsciously. With those socio-economic themes that we present, hopefully the film can be the beginning of a conversation about that. But, more than anything, I want people to have an experience watching it and get swept away. I got moved about that moment in time, of your adolescence, where seemingly anything is possible. The juxtaposition to that, in a world where people would think the possibilities aren’t the same, and for the things that happened while we were there, is incredible. It is about that moment in time, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that that’s what the future is going to be, or that that’s what the past was.

Martin: It’s an opportunity to celebrate those possibilities, but also recognizes that the community where these kids grow up, some of the decisions they make, at that moment in time and at that point in their life, could have dire consequences and a greater ripple effect.