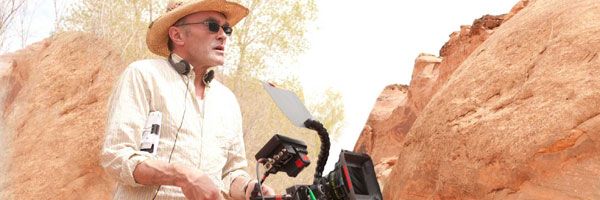

The biggest constant in Danny Boyle’s career is change. The 54-year-old director left a successful run in British theater and television to tackle a striking range of genres on film: horror, romantic comedy, family drama, thriller, dark comedy, among others. This weekend’s limited release of his real-life man vs. nature film, 127 Hours, marked the first time Boyle has let one actor fully drive a film. The venture paid off with a lead performance from James Franco that is getting rave reviews and the lion’s share of early buzz for the upcoming awards season.

This will also be the Oscar winner’s last directorial effort on film for some time. Boyle is the artistic director of the 2012 London Olympics Opening Ceremony and will smooth that transition from film to live events with a return to theater as the director of a new adaptation of Frankenstein at the Royal National Theatre in England. He recently gave Collider a host of new details on the play, how 127 Hours was inspired by Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler, revelations about his real-life subject Aron Ralston and why Slumdog Millionaire is far from his last production in India. Hit the jump for the full audio and transcription.

Danny Boyle first came upon Aron Ralston’s story in newspaper accounts and when the climber told of his harrowing experience in a televised press conference on May 8, 2003, just one week after his escape. The then-27-year-old survived for more than five days with his right arm pinned below the elbow by an 800-pound boulder in a narrow canyon after he slipped and fell while climbing. As detailed in his best-selling book Between A Rock And A Hard Place that is the basis for the film, Ralston cut the arm off with a dull blade to escape. Still losing mass amounts of blood through the tourniquet, he rappelled 60 feet and walked five miles before finding help. In 2006, Boyle and Ralston met to discuss a big-screen adaptation, but Ralston did not want to give up creative control and had a very different approach than Boyle’s first-person immersive vision. After the worldwide success of Slumdog Millionaire, the two met again and Ralston was more open to Boyle’s ideas.

Boyle started our discussion by answering a question Collider posed to Ralston at that morning’s press conference. The director liked our inquiry about advice for the recently freed Chilean miners in dealing with the sudden fame and onslaught of media brought on by their ordeal. Boyle felt Ralston might not have fully responded because he had such a difficult time dealing with the sudden loss of media attention after going through an extremely emotional rollercoaster from the experience, subsequent recovery and intense ensuing spotlight. Click here for the full audio or read on for the transcript.

-

Danny Boyle: Dealing with the media, if you’re that way in kind, is quite good fun and he’s not shy, Aron. He’s done public performances of the piece and written a book and things like that, so he wants to share (his story) for all sorts of reasons but I think once it dies, that media interest, that’s the problem you’ve got then is that aftermath and you are left with the, the experience, re-living the experience in your mind. But you’re left alone with it really, in a way, or you can be and I think he went through quite a low period there and he emerged out of it. He met this, his wife and she has clearly had a huge impact on him ‘cause he’s changed as a person. You can see and I think the true completion of his journey has only arrived because of that, because of meeting his wife and then obviously they had the child, which you see in the film. The timing of that is extraordinary and it allows us to complete his journey as a compressed 90-minute event, but I think in reality it took him many years to fully complete the journey.

[Note: Ralston was airlifted directly from the canyon into a 17-day hospitalization after he lost 40 pounds and a liter of blood over the 127 hours and required three surgeries in five days. Ralston said his ensuing physical and mental recovery with his parents was complicated because he “was also on a lot of painkillers and narcotics (Vicodin, Oxycodone, Dilaudid) that just had me essentially drugged into a stupor if not, outright sleep for months.” It hampered his connection with friends and family that drove or flew to see him in Colorado from around the country. He said after the spiritual death and re-birth in the canyon, he experienced a second re-birth at home, where he was, in his own words, like “an infant under the care of my parents” that mirrored an “accelerated childhood.” It included an intense push-and-pull with his parents over independence on acts like going for a run or heading out on the town with friends.]

It sounds like an Eastern philosophy almost. At the press conference, he talked about his (spiritual) death and then the re-birth and “growing up” again with his parents and then, as you were saying with-

Boyle: Yeah.

-the death of the media that he almost died again before meeting his wife that it’s, he goes through this circle. This is the third time now that he’s been re-born in that constant quest for himself.

Boyle: Yeah.

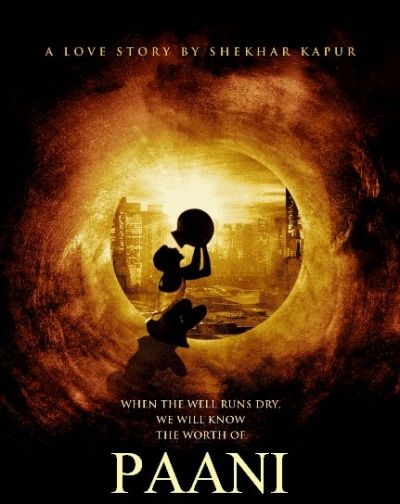

And I’m interested, concerning you (and the influence of India on his work). You come off of Slumdog Millionaire and then you’re listed on Paani as a producer and Maximum City, as well (both projects are set in India). Well, first of all, are those happening? I’ll get back to the original question in a second.

Boyle: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Paani (which means “water” in Hindi) is a Shekhar Kapur (director of Elizabeth and Elizabeth: The Golden Age) film (a drama set 30 years in the future about the battle for the world’s dwindling supply of water) and I’m a big supporter of Shekhar so I’d love to, if the film happens, I’ll certainly support it in that way. I’m not involved in it day by day and I haven’t spoken to Shekhar in a while. He’s working on the script at the moment like that. Maximum City, (based on a book of the same name about Mumbai’s criminal underworld) I would have loved to adapt that, but I couldn’t find a way to make it work at the moment so that’s not gonna happen right now. Although, I’m still drawn to making a film either based on Maximum City or loosely based on that idea of a, a thriller based around that city (Mumbai). I’d love to make a film like that one day.

But you are so impacted (by India). Clearly, going through an experience from Slumdog Millionaire, not only shooting there, but also still being involved with the lives of those children years after-

Boyle: Yes. Oh yeah. We will be. We will be for a long time, yes. (Boyle and the film’s producers have set up a trust fund for Slumdog’s child actors)

And I’m interested by the influence of Asia and India in particular upon your career-

Boyle: Oh, right.

-and how that completely transformed you because as we’re talking about Aron and he went through these re-births-

Boyle: Yeah.

And that’s very comparable (to) Eastern religion as well. What was the impact that it had on you?

Boyle: It did have a profound impact upon me. I found it an incredibly generous place, despite the poverty and despite the pressure of life there, of the crowding and the sense of people hassling and trying to take advantage of a circumstance if they could. I still found it a very, very generous place and I learned a lot about myself there and about directing.

What, what did you learn most?

Boyle: I learned about being a bit looser. Normally, I’m a very controlling director. Directors ARE controlling. It’s part of the job, but there’s various degrees of it and the constructs I normally work on are very controlling constructs. There was a very complicated construct in Slumdog, but the ingredients within it had to be let loose. The only way you could film in Mumbai was to trust the city. You couldn’t control it in the way you would do normally as a location. It would offer up things for you and you had to be in a position where you would grab them. And then on 127 Hours, I, I was less controlling of an actor than I’ve ever been. Ever. And I knew in doing a solo film like this, that you couldn’t control an actor. If an actor looked controlled or manipulated in any way, it would just collapse the thing and I’d seen Darren Aronofsky’s (The) Wrestler, which I liked very much and I remember thinking when I saw it ‘cause I like Darren’s work and he’s, as a director, he’s not unlike me. He likes to manipulate the camera and the screen and get a bit of sparkle going and, visually, and things like that. But I remember him making this plain film with Mickey (Rourke) at the center of it. Boom. Mickey was absolutely generating the film and I thought, “I’d like to make a film like that.” Part of a director’s skill set should be a film like that and this was the opportunity to do that was to work with James and to let him dominate the f-, if you look at all the other films I’ve made, no actor dominates a film that I’ve made like the way that he dominates this one. You know?

Well, yeah, because there’s so much in the ensemble with Slumdog-

Boyle: Yeah.

-and with Trainspotting and-

Boyle: And lots of other films.

- A Life Less Ordinary, which was also shot in Utah (as was 127 Hours).

It’s interesting, though and I am a little puzzled when people say that it’s such a different film from Slumdog Millionaire because it’s not.

Boyle: Not really, no.

Not really at all! Yes, the plot (is different), sure, but they’re both in very confined spaces. You’re shooting in confined spaces throughout. (The characters are) striving towards sunlight, whether it’s literally in 127 Hours, or figuratively with Slumdog. And it’s this striving of, you know, the human spirit is such a corny way of saying it, but they’re very, very close, they’re both striving for the connection and they’re also at their last end to make that connection, whether it’s in Slumdog or whether it’s here.

Boyle: Yeah.

Do you-?

Boyle: Yeah! There are some similarities and you some- sometimes you’re aware of them in films and you bump into them on the film set. You’re suddenly aware of, “Oh, I’ve been here before” or it’s afterwards that you kind of really get the connection.

When you first saw the press conference that Aron gave, that you were talking about at the press conference today, did any of that, as you were thinking of how to tell the story, did any of that play into it? “I’ve dealt with confined spaces before?”

Boyle: No, it was when I read the book in 2006; I began to get a very clear idea of how to make the film. Or what I thought was a clear idea of how to make the film. Now that was before we made Slumdog, but I think you’re right, this is quite literally a struggle against the odds, but it’s, that’s true in some of the other movies, as well. Particularly, Slumdog, he’s struggling against the odds, for sure. But there was also something about the role of people and it was why we put in the beginning triptych of this film (127 Hours) some shots of Indian crowds, as well. ‘Cause there is a connection there, because the thing people fear most in Mumbai, and this is in Maximum City actually. It’s very eloquently written in Maximum City by Suketu Mehta. People fear loneliness, more than any other single thing. It’s so crowded, life. You’re so surrounded by people. Everybody grows up, sleeping six in a room and the loneliness you fear is that you’ll be on your own in a flat on the outskirts of Mumbai. That’s the terror they all have. And that’s the terror they have that modern society’s gonna try and impose on them. And it’s why they’re quite protective about the slums, about maintaining that society. Even though the physical conditions they’re in, from our perspective, are unacceptable, from theirs, they’re an inconvenience, compared to the benefit of all living together.

So, suddenly you then go to this story (127 Hours), which is about a guy (Aron Ralston) who at the beginning is turning his back on those kinds of crowds, as though he doesn’t need them, because he’s got his individualism. He’s a self-sufficient, independent, an achiever. (Repeats for emphasis) An achiever. He was, turned his back on Intel Engineering because, you know, he “don’t need any of this.” He doesn’t need anybody. And he climbs solo. And he didn’t tell anybody where he’s going. And he finds the emotional journey or spiritual journey of the film, is he finds that he, not only does he need those people, those people will pull him back if he will let them. In some way, they will pull him back into life again, really. And that’s why he hallucinates about a kid. He’s 27. The last thing on his mind is parenthood. And in the midst of his journey, he sees this child and he knows it’s his. It’s not a Jesus, Buddha, Mu-Muhammad thing; it’s not a kind of religious thing.

It’s clearly his part in a lineage, which he’s not even aware of, yet. That lineage is the supreme way in which an individual realizes it’s not about individualism. You live your life and it ends quite quickly and all you can do with it is pass it on decently to someone else. Whether directly or indirectly, behave decently to other people. That’s basically all that (is). And he learns that lesson through it. And that’s why the specific memories (Aron has) are about people that he has not really appreciated as much in his heart as he could’ve done and when he (arrived) at that moment, he gets a route out: the kid (child in his premonition). It’s suddenly a direct route out of the- and he literally says in the book ‘cause he strained to try and reach the child. He felt the bone bend in his arm and he knew he could break it and he’d never thought of it before that moment.

Yeah. I’m interested in (Boyle’s upcoming theatrical production of) Frankenstein because you’ve been talking about it for eight years. The Royal (National Theatre which houses the Olivier where the play will be) is known for musicians and employs a lot of musicians. So, will you score it?

Boyle: Well, I’m hoping to kind of musically score it to a degree, but it’ll be a play of performance and speech and there will be some musical elements in it (but it won’t be a musical). Quite how much, I don’t know yet until we start working on it, but we have an unusual perspective. We’re doing it from the point of view of the creature which has never really, as far as we can tell, has never been done before despite the fact it’s had myriad adaptations and distortions in movies and things like that. But the core of the story, we will re-think through this unusual perspective. So the evening begins with the birth of this creature. It opens its eyes and it’s born. 30 years old, but born. You know, day one.

Is this the middle step for you, coming back to theater before doing such a huge live event like the opening ceremony (of the 2012 Olympics in London)? Is that why you came back to theater?

Boyle: Well, it was all accidental, actually, but I’ve been trying to make sense of it in retrospect and I’m hoping it does (laughs) it does fulfill that, yes and hoping it helps me get ready (for) a live performance before we do the HUGE live performance at the Olympic Games. Yeah, so, we’ll see.

Thank you so much.

Boyle: Ok, cool. Thank you.