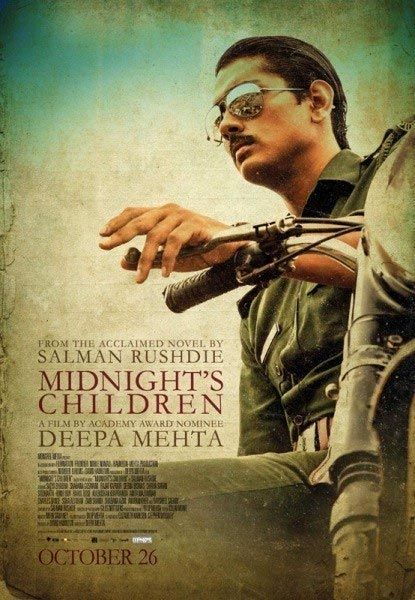

Opening this Friday is Midnight’s Children, an epic film from Oscar-nominated director Deepa Mehta, based on the Booker Prize-winning novel by Salman Rushdie. At the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, as India declares independence from Great Britain, two newborn babies are switched by a nurse in a Bombay hospital. Saleem Sinai (Satya Bhabha), the illegitimate son of a poor woman, and Shiva (Siddharth), the offspring of a wealthy couple, are fated to live the destiny meant for each other and their lives become inextricably linked to India’s identity.

At the recent press day, Mehta talked about creating a film that’s sweeping in scope yet intimate in tone, which films and filmmakers influenced her approach, how she assembled the diverse ensemble cast of American, Bollywood and Indian theater actors, the unique color palette she chose to convey the story’s passion and magic and conjure up rich and unforgettable images, the challenges she encountered bringing the book to life on screen, the production delay in Sri Lanka caused by Iran, how she convinced Rushdie to narrate the film, and why she found their collaboration one of the greatest experiences of her life. Hit the jump to read on.

Question: This is a beautiful film. What influenced your choices in terms of the look and the visual style?

Deepa Mehta: Thank you very much. While we’re working on the script, I never see any films. I make it a point because I don’t want to get distracted. I don’t want to be influenced, and before I know it, have somebody say, “My God, she plagiarized that line.” The whole thing is so subconscious. I just don’t see films. But once the script is done, I put it aside for a month. I start thinking of all the films that have influenced me, which I have liked for different reasons, and not necessarily the look, but films that have moved me. Some very strange films came to mind. For example, Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard had a lot to do with the way I approached the look of Midnight’s Children because it’s a film that’s classical in a sense. The framework is the widescreen. The camera moves because the characters are motivated to move. The characters don’t follow the camera. The camera follows the characters, which is something that I really wanted for Midnight’s Children. Also, it’s an historical piece which is seen through the eyes of a family. So, The Leopard really influenced me. The other film which inspired me a lot for a totally different reason was Ugetsu by Kenji Mizoguchi, which is a brilliant, black and white, late 50’s Japanese film about magic realism, because it deals with a ghost that in fact does not feel like a ghost. It’s a precursor of, but far more sophisticated than, The Sixth Sense. It’s that sort of ambiguity. Where does reality end and where does magic realism start? There was another film called Time of the Gypsies by Emir Kusturica who is a brilliant Serbian filmmaker. But again, it’s the same way he dealt with magic realism. You have all these things that inspire you. It’s not that you’re going to make them your own, but it gives you a stepping stone.

The other thing that I do when I pick up the script again is I always decide, for some odd reason, what the emotional color of the script is. For me, the color of the story of Midnight’s Children in the script was red, because there is a lot of passion and a lot of blood. I felt that it should be blue, ranging from royal blue to deep midnight blue, which is the color of midnight, the lack of color, and green because it’s about fertility and hope. Those three colors, once they were defined in my head to me, became the basis of the color palette of the film. Once I had the color palette of the film, then I worked with the production designer, and we decided not just the authenticity of what the furniture is going to be like or the house is going to look like, but the detail. I mean, okay, we’re sitting at a table with a white tablecloth, but what are the colors of the chairs. They became either green or blue or red, and it was the same thing with the wardrobe. The colors start seeping into everything. That’s how I work with my cinematographer, my wardrobe designer. What are the colors? Who’s wearing what? Why should they be wearing this? Why should Parvati be wearing blue and a bit of red? When does she stop wearing red? Parvati is the witch and she’s always wearing blue and red, which is the color of magic for me. That’s how you decide. It’s a lovely process. It’s one of the most exciting parts of making films.

What were the biggest challenges you faced in bringing this story to life on screen?

Mehta: There were many hard things. It’s a film that is very epic in its nature. It spans 60 years. It has a cast of thousands. It’s an ensemble piece. It has 16 main speaking principal roles. There’s a scene I call “The Killing Fields,” which is the massacre in Bangladesh where we had maybe 1,500 extras who were various forms with wardrobe and make-up. They were all butchered and lying out in the swamps. It was a very difficult scene to shoot because it turned out there were snakes in the swamp. That wasn’t much fun. And there were mosquitoes. It’s 118-120 degrees and they can’t move. Scenes like that are tough. There’s also a scene in the film where Saleem’s nanny tells the family who are having breakfast around the table in the morning, “Your son is not your son. I swapped him.” If you think about it, compared to a scene with 1,500 extras, 120 degrees, all of them needing make-up because they’re supposed to be bleeding, that was a tough scene, too. It’s emotionally difficult and everybody’s emotions have to be right because everybody has a different reaction. The mother has a different reaction. The father has a different reaction. The boy himself has been told, “You’re not your mother’s son.” It’s shocking. For me, to get that cadence and that tone right was the most difficult.

How much did Salman Rushdie have to do with the film? Was he a consultant? Was he there for any of the principal shooting?

Mehta: No, no. Not at all. He was wonderful. One of the most enjoyable experiences of my life was working with Salman. Not only is he very bright, but he’s also a very generous man, a very funny man, and he doesn’t take himself too seriously. It was just wonderful. We worked together. He wrote the script and we worked very closely on the script. And then, I’d toss somebody and I’d ask Salman, “What do you think of this person? Check this one out.” I wanted him as involved as he possibly could be. It’s his first book being filmed. It’s an iconic book. When he finished the script, he handed it over to me, and I said, “Why don’t you come with me shooting?” And he said, “Listen, there is only one director. Best of luck. Have a great time. I trust you. Show it to me when it’s finished.”

Isn’t that unusual? In Hollywood, they rarely let the writer near a production. The director has the script, and if he’s going to mess with it, he doesn’t want the writer to complain.

Mehta: That’s what they do. They mess with stuff. I know that they tried to do that with The English Patient with Anthony Minghella, and he said, “Absolutely not.” And that’s why they pulled out, in fact, which was great because then he actually got to do what he wanted to do. Michael Ondaatje who wrote the book, The English Patient, was very deeply involved, as was Yann Martel with Ang Lee for The Life of Pi. If the writer is secure, if the director is secure, then it’s a very important marriage and a relationship. The reason I wanted to do Midnight’s Children is because I loved the book. Why would I want to not have the writer at least know what’s going on? It would be terrible. Can you imagine showing the film right now to Salman Rushdie and he says, “I hate it.” How horrible.

The story covers so much about the independence of India. Is it hard to capture that history accurately in two hours?

Mehta: It’s really 30 years. When you think of 30 years, it can be done. It’s not that big. It’s the independence of India. It’s not as if huge trials and tribulations happened. Yes, there were three wars. Yes, there was a dictatorship, the emergency of Mrs. Gandhi. I think things are explained in human terms, and that’s why Saleem’s journey is so important. This poor guy is lost. He’s being sent off to war. He doesn’t even have a memory of what happened. All he’s doing is feeling the loss of his parents. If you feel for him, then you’re invested in the character. If you’re invested in a character, then you can tell any history that you want to. Then it’s not about a history lesson. I feel with Midnight’s Children, yes, it is about post-colonial India, but it’s not a lesson in history. A country mirrors its people, and a people mirror its country. So, if you follow Saleem’s journey, you will naturally follow the history. It wasn’t rocket science.

Was the film’s 2-1/2 hour run time dictated by the script?

Mehta: No, the first draft of the script was 276 pages, so it wasn’t. We talked, and I read it, and it was great. I said, “Oh wow, we can have a sequel. Part I and Part II.” But nobody would want to finance Part II, so that was that. And then, it became obvious that it was a very good exercise. Okay, what do we want to pay attention to? That was the first draft. By the time we got to the final draft, it was 130 pages. It wasn’t dictated by anything else. I think the film is about 2 hours and 20 minutes. I felt like that’s what the story felt like. We weren’t told that we had to have a cut-off point or anything.

How did you find such a diverse cast? You’ve got American, Bollywood and Indian theater actors.

Mehta: It was great. One of the things that I really love about doing a film is working with actors and the whole casting process. I feel I’m not looking for actors. I feel I’m looking for characters. If the characters come from Bollywood, fine. If they come from Indian theater, perfect. If I happen to see Satya in a play at the Yale Drama School, fine. It doesn’t matter. I got somebody that I saw who was sitting across from me in the subway. I thought she was just lovely. I said, “Who are you? Do you act?” And she said, “I’m actually looking for a job. I’ve never acted in my life.” I said, “Would you like to try out?” and she said, “Sure.” In fact, she became Saleem’s mother, the musician’s wife. She’s never been in front of a camera in her life. It’s all about feeling comfortable, which should be good for the character. It’s all about the character. In the end, when you think of a film like Midnight’s Children, or even the last film I did which was called Water, whoever I have in it, even if they’re a big Bollywood star, it’s not going to help it sell in Italy or Germany because people really aren’t that aware. Maybe it will help with the diaspora. But the diaspora, they’ll go to a Bollywood film but they will not generally en masse go to what they consider too serious a film. So who does it help? You might as well cast somebody who’s right, as opposed to just for the name. It’s like having Brad Pitt in every film.

Did you foresee any challenges working with Rushdie’s material? I understand you were asked to stop shooting for a few days in Sri Lanka. Were you concerned about that at all going into it?

Mehta: No. Not at all. The fatwa is long over. Midnight’s Children is a book that has never been controversial. It’s not The Satanic Verses. I know a lot of people seem to think it is The Satanic Verses. It’s never had any problems. It’s a Booker prize-winning novel. It’s the book that’s been celebrated, and the fatwa is very old. He’s been living in New York without any security for years. So there is no fear at all. I wondered if we’d be allowed to film in India for some reason, mostly because of me, because I had a difficult history of filming Water in India, and I wasn’t allowed to, and I could only film in Sri Lanka. But then, for two days, we were stopped because the foreign minister in Tehran learned that the Salman Rushdie book was being filmed, not The Satanic Verses. According to them, none of his books are allowed to be filmed anywhere in the world. It was bizarre. They actually called the Sri Lanka Film Board and said, “Please stop the filming.” When we were about to start shooting for the day and we’d already shot for 30 days, they came and told us, “Sorry, but you don’t have permission to shoot.” “What do you mean we don’t have permission to shoot?” And they said, “It’s been taken away and we don’t have to give you any explanation.”

I said, “This is ridiculous. Let’s go to the president of the country who gave us the permission.” It turned out that the president was away in the interior of the country for some election and was not reachable. It’s really scary, because you have a crew of about 150 people, you have cast members from all over the world, and you’re just sitting there. Every day costs a lot of money when you’re not shooting. For two days, we sat around, and then the president came back to the capital, and we went to him and said, “This is what happened.” And he said, “How dare they! They cannot bully us.” And so, we started filming again. It wasn’t that bad, but it was sad. It was not expected. You never know about Iran. What do you do? I’m sure all of you have seen Argo.

How was this different for you from filming Water which was told through a woman’s eyes?

Mehta: I loved this film, because in fact it’s also told through a woman’s eyes because I am a woman. There were two reasons that I really wanted to do this film. One was a very important theme that has a lot to do with me being an immigrant from India to Canada, which is, the journey of Saleem is the journey of a person finding home. What is your family which you’ve left behind? How do you define your identity? What is it like to be an exile whether you come from Brooklyn to San Diego or whatever? People are always on the move now, and we are always constantly redefining ourselves, whether you’re a student and you come from Louisiana to USC or whatever. It’s always finding friends who are our family. You have to make up families again because you leave them behind. Saleem’s journey is a journey not only of a country finding an identity, but of a person finding his identity, and I find that very universal. The other thing that attracted me to the film, and this is to get back to your question, is that it has very strong female characters. And so, it was very interesting seeing the journey of a male protagonist who actually is defined by all the females. Saleem is what the women around him make him. For me, it’s a very strong female film.

Can you talk about the identity of India within the context of this film?

Mehta: You know what’s happening in India right now, whether it’s the diaspora, which is outside India, or within India? There’s a lot of migration happening within the country itself, so you have people from the North East, from Assam in North East India, who a couple of months ago moved into Maharashtra which is the state that Mumbai is in. There was such confusion because they said, “You are not wanted here. You aren’t indigenously from this province so you have to go back.” They were actually thrown back. This is within a country. So these poor migrants are being shunted all over the place. There is such nationalism which is creeping into who we are and what we are. How was it defined? That is what Midnight’s Children in many ways is about. It’s about trials and tribulations of a people. I have to go through whatever I have to, and it isn’t necessarily good or bad, but finally, there’s hope. That’s when he says at the end, “We’ve been through whatever we have, the country and me, but still, finally it’s all about the acts of love.” It’s a hopeful film. Don’t judge us. We’ve done it all. And we’re still struggling. I think now what’s happening is there’s a bit of arrogance in the diaspora, because the diaspora is always defined by what’s happening in the motherland. How we feel about ourselves outside India is dictated by how India feels about itself. When India was in the doldrums, it was perceived as a third world country which was filled with beggars, was dangerous and was where you got malaria. Don’t go there. And then, it was a country that had been visited by hippies. Then it became a country that was Bollywood. And now, it’s become one of the BRIC countries with an economy that’s really rising. And so, that has brought a lot of confidence in the diaspora. The diaspora can look at the Caucasians that are surrounding it and say, “Hey, we are something,” and it’s because the economy is doing well.

Why did you leave India?

Mehta: Oh my God! Why did I leave India? I fell in love with a white man. That’s what it was. It was the most boring, predictable reason in the world. I met him in India, we fell in love, and we got married.

That’s wonderful.

Mehta: And then, we got divorced. Sorry about that.

What led to Salman Rushdie becoming the narrator for the film?

Mehta: When we finished editing the film and we had the fine cut of the film, I looked at it and I said, “Oh my God, there’s something that’s really missing.” Of course, for me, what was missing when I thought about it was the language of the book. In the film, there is very little dialogue. It isn’t too dialogue heavy. Nobody gives long lectures. It’s certainly not like seeing Lincoln. It’s really very small. The sentences are small and everything. Also, because we wanted it to be authentic, some of the dialogue is actually in Hindi, which is the language. It’s in Kashmiri. What happened in the film was I feel that we missed out on something that’s stunning in the book, which is the language of Salman Rushdie. So I thought maybe we should get a narrator, the older Saleem looking at his life and ruminating about it. It is an opportunity to use some of the language of the book. I spoke to Salman about it and he said, “That’s a good idea.” He wrote a few things, and they were stunning because they’re not about exposition. The narration doesn’t drive the plot forward. It gives you a feeling about Saleem and what he feels. We used the language of the book. And then, I tried a few actors to play the older Saleem, to narrate it, but it just didn’t sound right. They sounded too much like actors. Again, I got this idea and Salman was ready to kill me. I said, “Why don’t you try?” He said, “Absolutely not. I’d loved doing it. I love the performances, but I’ll be the weakest link and I don’t want to be.” And he wasn’t. I said, “Let’s try it.” He actually did two of the narrative bits and my wonderful editor, Colin (Monie), put them on film and then we showed it to Salman. It worked so beautifully. I think that’s because it’s so organic. It was lovely. Of course, I was thrilled because we got the language of the book.

Was there anything that you wanted to modernize about the tale in telling it?

Mehta: I guess like doing Richard III in a bank or something? They do that. No. It did strike me once, but I thought then it becomes about trying to be cool and contemporary. This is a very classical book, and I felt it should be treated that way.

You mentioned India’s changing identity and how the economy is different now. Did any of that come into play?

Mehta: No, because it’s a different India. I don’t know how you could impose it on that. I guess you could do anything with film, but then why use this book? A story about identity could be done, but the politics and the emergency, what would you do?

Do you see the book’s story differently now than you might have 30 years ago?

Mehta: I do see it differently. That’s why it is [different] in many ways. If you read the book after having seen the film, you’ll find that there is a different take on the novel. It’s very true to its essence, but the way it has been achieved is different, and even the narrative line is different. So, in that sense, it’s different. But I don’t think that I could have imposed 2012 on it. You should read the book now and then you’ll see.