Earlier this summer, Collider favorite Edgar Wright posted a list of his favorite films from cinematic history. It wasn't a Top 10 or even a Top 100, but a list of 1,000 movies culled from over the last century. You can find the full list compiled by Wright and Sam DiSalle here, which comes with a word of warning from Wright himself:

This is a personal and subjective list of 1000 favourite movies from 100 years of cinema. It’s not a set text or intended as any bible of ‘greatest’ films. I decided to put this together as a fluid list for my own enjoyment, amusement and reference. I hope it’s fun for you to pore over and dive into some of the films you haven’t seen or haven’t heard of.

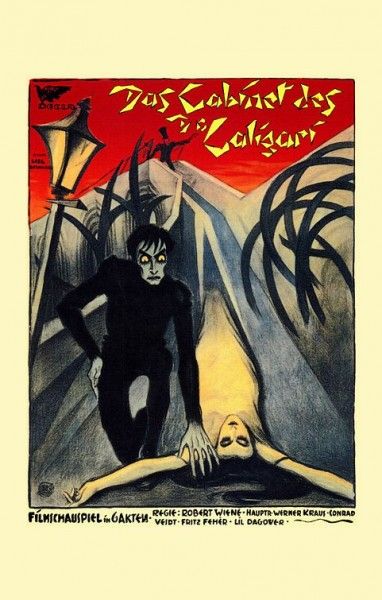

Due in part to some encouragement from Wright's words and to some sort of self-flagellation of our own design, we've decided to revisit each of the films in this list and provide you with a weekly review. If we make it all the way to the end, and if you stick with us, we'll stumble across the finish line together in just over 19 years from now. Like Wright, we'll be tackling the films chronologically. So for our inaugural review, we bring you, Robert Wiene's 1920 German Expressionist classic, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Image via Archives du 7e Art/Decla-Bioscop[/caption]

Like any of these films that are not only foreign to us here in the States as far as nationality goes but equally unfamiliar in terms of their place in history, an analysis of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari first requires a little bit of background. (I'm no expert in Post-World War I cinema or German Expressionism by any means, so if this cursory examination interests you, please follow up with your local university, library, or hipster cinephile for more.) Written by Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer--a Bohemian-born German author and an Austrian-Jew respectively--who emerged from World War I as pacifists distrustful of authority, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari draws directly from their experiences with the military.

As prevalent as the anti-authoritarian message is in this film, the jagged landscape, heavy shadowing, and unnatural angles are even more so. This chaotic appearance emerged from within the wider cultural movement of German Expressionism, a style named as such due to Germany's wartime isolation, which led to artistic experimentation in the absence of outside influences. Thanks to small budgets and a rationing of electricity use, filmmakers during this time used non-realistic set designs composed of geometric absurdities with designs, fixtures, and even shadows themselves painted on the often paper-made set dressings. Since The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari dealt with both authority and insanity, and the surprisingly thin line that exists between the two extremes, both the cinematography and the production design complemented the madness that lurked within.

Before audiences ever get into the main story, they're introduced to a prologue that served as the first bookend of a controversial frame story. You could write a book--and people have--on the behind-the-scenes drama regarding the inclusion of this frame story, which some critics see as undermining the anti-authoritarian message in the story proper.

At the outset, a young man named Francis (Friedrich Feher) sits with an older man who is anxious about the spirits who have driven him from his home. As Francis' fiancée Jane (Lil Dagover) passes by them in a daze, he relates a terrible story of murder, mystery, and the supernatural that plagued him in his past.

It's this core story that introduces the title character (Werner Krauss) and his mystical cabinet, one that contains the ever-sleeping Cesare the Somnambulist (Conrad Veidt). They have come to Holstenwall, a shadowy village of twisting streets and steeply sloped mountain passes, to attend a festival where Dr. Caligari's carnival barker antics are put on display. Caligari first appears as a hunched old man shambling through the twisted streets with the help of a cane, but once he steps up to the stage to entice townspeople to approach his fortune-telling sleepwalker in order to discover their fates, Caligari becomes youthful, passionate, and disturbingly animated. What follows is a series of murders that rock the small town in the dead of night. And if you think you know the culprit, chances are that you're on the right track, but the ultimate reveal still holds up quite well almost 100 years later.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari should be appreciated for it's historical significance, cultural impact, and cinematic contributions, but the story and its unique presentation is just as enjoyable today as it was in 1920. There's an honest criticism to be had regarding the framing story and whether or not it undermines the message of the main tale--that absolute power corrupts absolutely, or that authority is not to be trusted without sufficient checks to balance its power--or whether it simply provides an enjoyable twist to a macabre story, one that is oft credited with founding the genre of modern horror movies.

Image via Archives du 7e Art/Decla-Bioscop[/caption]

It's a little unfair to review this classic film now thanks to the wealth of more thorough criticism and research into its impact that the intervening decades have provided, just as it's rather unfair that I can simply view this classic film in the safety of my own home on a handheld device rather than in a darkened post-World War I theater. In the modern era, the haunting visage of Caligari and his Somnambulist harken back to the earliest roots of horror that cinema have to offer. But in that latter setting, one that saw audiences spilling out into dimly lit streets where the creeping dread of Caligari could easily be imagined to be lurking around every shadowed corner, I'd wager the immediate effect was quite dreadful, and the lingering horror that followed audiences into their bedchambers even more so. As we all know, in order to truly understand Dr. Caligari, "Du mußt Caligari werden!"

If you liked this initial installment, be sure to return next week when we revisit another hallmark of German Expressionism, F.W. Murnau's 1922 horror film, Nosferatu.