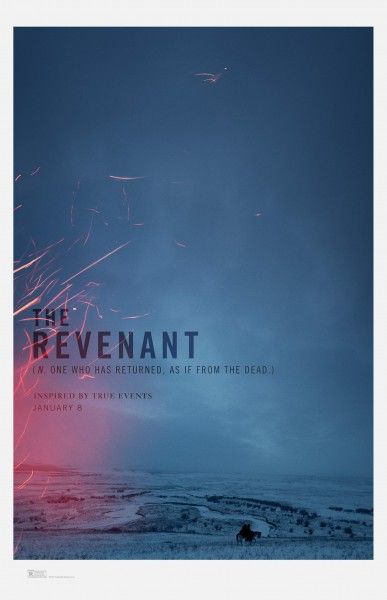

If you love movies, you’d better know Emmanuel Lubezki’s name. That’s because as the cinematographer of Gravity, Birdman, Children of Men, Y Tu Mamá También, The Tree of Life, The New World, Sleepy Hallow, and a host of other great looking movies, Chivo (his nickname) has won back-to-back Academy Awards for Best Achievement in Cinematography and is definitely going to be nominated again for his unbelievable work on director Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s The Revenant. As you’ve seen in the trailers or any of the footage Fox has released, Lubezki’s breathtaking cinematography is one of the major selling points because he shot the film using only natural light and in locations never seen in the movies. Trust me, The Revenant is one of those special movies that should be seen in a movie theater on the largest screen possible. The film stars Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hardy, Domnhall Gleeson, Will Poulter and Forrest Goodluck. You can see DiCaprio and Hardy and Gleeson and Poulter talk about working with Chivo by clicking the links.

At the recent press day in Los Angeles, I landed an exclusive interview with Lubezki. He talked about making The Revenant, the rumors that they were going to shoot it like Birdman (i.e. to make it look like one long take), the challenging shoot, if he’s involved in the editing process, film vs. digital, if he wants to use IMAX cameras in the future, memorable moments from filming Children of Men, and more. Check out what he had to say below.

COLLIDER: This is a great year for me because I spoke to Roger Deakins and now I’m speaking to you, so I really don’t know where to go from here. As a film nerd, I don’t know where to go. It’s all down hill.

EMMANUEL LUBEZKI: Thank you so much.

Tom Hardy said that The Revenant was originally going to be shot like Birdman and made to look like a single take, but the weather made them change it. Is that true?

LUBEZKI: No. With all due respect to my friend Tom, we never thought we were going to shoot the whole movie in one shot. It would be preposterous and you know these movie takes plays in many, many months of these journeys to survival and we will never attempt to impose a language on the movie that is not required to tell the story at all. The language of Birdman was very much found and created for that specific world and for that specific story and the language of this movie that is very different was created after a lot of rehearsals for this specific project and never, never, we never thought about doing it in one shot.

I’m sure you’ve been asked this before but let me ask it again: what you guys did on Birdman was such an achievement and so challenging. After looking back on it now, if a project ever came up and it made sense to do one continuous shot, would you do it again?

LUBEZKI: I mean, what you don’t want is to repeat a formula over and over or impose a formula to a movie that…when you impose yourself and you impose a formula and you’re not open to explore and to find what is right for the movie, I think you’re doing a disservice to the story and what you’re trying to express. So what you want is every time you start a movie is to explore with a director and if you can with the actors and with the other collaborators and try to figure out what’s the best way to tell the specific story and by doing this and The Revenant and doing these extensive rehearsals, we found what we thought it was the right way and the right language and the right tools and the right colors and environments to tell this very specific story.

How involved are you in the editing process, or when you leave set, that’s that?

LUBEZKI: In my contract when I finish a movie and shooting, that’s that, but in the case of my friends, with Terry [Malick], Alejandro [G. Iñárritu], with Alfonso [Cuarón], with Rodrigo Garcia, as with those directors I am as involved as I can in the sense that I go to the editing room and give them notes and watch the movie over and over and over and if I’m collaborating with an artist I like to give them my point of view and if they don’t want to take any of my recommendations it’s fine, but it’s hard otherwise. I think it’s part of the process, to start the movie and go through all the processes until you’re done. That’s the cinematographer. It’s also a way for me to learn if what we’ve done was right, and if our instincts were correct and if we achieved what we wanted, the only way to do it is by going to the editing room, and also that teaches you for the next project will be a much better collaborator if you know all the tools, if you know how to cut a film.

Everyone talks about how challenging this shoot was. Were there one or two days that you will always remember, whether it be because of a shot you got, or because of a challenge you overcame, or just because you laughed a lot?

LUBEZKI: You know, I think I’m going to remember many, many days of this movie. I think it was so challenging, every day was close to failure and brutal on the body that in a way going through this experience, it makes you much more aware of your surroundings and what you’re doing and you’re more in tune with the present, so because of that I think I have many, many memories of the film. I don’t know if there’s one specific.

What camera did you use for this, and did you always know it would be that camera, or was there a lot of debate?

LUBEZKI: Not debate, but again you’re not trying to impose a formula onto the movie. One of the methodologies that Alejandro likes to use is to go and rehearse, and use the rehearsals to find the tone and the style and the language of the movie, so when we were doing that, we had a bunch of equipment and we had a few actors and stunts and extras and sometimes we brought gear and wardrobe and so on, and as we were rehearsing we were trying to find what was the best way to tell the story and one thing that we really wanted to do was to immerse the audience in this world, to make a very immersive film where you could almost feel the cold, the weather as you were watching the movie. Little by little by doing these rehearsals we realized that we wanted to use very white lenses that allowed you to always see the environment where the story is happening and to be able to have a constant relationship between the internal struggles and internal world of the actors and the external forces of nature and the environment.

Once we figured out we wanted to use these lenses, we started to experiment with film. We’re both filmmakers and we’ve done most of our movies on film so we were very keen on using film. We liked the dynamic range that film gives you. You can get detail in the very, very highlights and also in the shadows and we also started doing some comparisons with the digital cameras, and even though the digital cameras don’t have the same dynamic range, the digital cameras are way more sensitive to light, so we were able to shoot at the times of the day that were more important and more interesting for us and more mysterious and poetic and as you know, in the northern latitude, the sun travels very, very low and goes behind the mountains a couple times a day, so when you’re surrounded by trees you’re really dealing with very low levels of light and the film was collapsing then, and these digital cameras were able to show stuff that I’ve never seen before in my work. I could never shoot at these times of the day, practically at night and when you shoot at those times of the day, the mood and the feeling is just completely different, and then makes the forest mysterious and it evokes a lot of emotion that all there was you could not get. At one point, with all the sadness of the world we packed the film cameras and sent them back to Hollywood and went with the digital cameras that were truly creating an image that was much more immersive, more visceral, more powerful, more expressive, that allows to shoot more time during the dark days of the winter. Also something that was very important for me was that I didn’t want to have grain between the audience and the characters and the environments of the movie. A lot of the piece talk about graininess as something magical and beautiful and poetic, but to me it almost feels like a curtain between you and the characters that is not allowing you to see this world, but immediately you know it’s a representation so you know that what you’re watching is not real, that it’s a movie, that it’s a representation, that everyone’s pretending to be someone, where the digital cameras even though you’re doing the same, to me it makes it more immediate and more immersive, so again we sent the film back and we went digital.

Which camera specifically did you use?

LUBEZKI: We used a NIM that allows me to do handheld cameras. The NIM is the one that splits the sensor from the recording device and if you’re a middle-aged cinematographer or operator, you love it because it’s lighter and also it allows you to get to places that the other cameras don’t. For example, when Leo [Dicaprio]’s son is dead and Leo crawls to him and puts the head in the chest of the kid, I was able to travel above the face of the kid one millimeter from breaking his nose off to arrive to Leo. That with a big camera was impossible. There was just not enough room for me and for the camera to travel to that specific zone of the frame, so the end is a very important tool that probably will be and now upgraded to the mini that it’s even more wonderful because you don’t have cables and stuff like that, but it’s still not recording rocks. I’m waiting for that patiently. And then we have the XT that is wonderful for the steadicam and crane shots and then we got very, very lucky when Ari called and said they had a 65 camera ready for us and they brought it to Canada, because it’s a camera that is changing the way we show movies to the audience, the way we can translate these images into the screen. It’s a game changer because of the quality of the image, the resolution, the size of the cheap, but also the lenses, the fact that you can shoot with a 24 and have the same field of view as a 12, but with a depth of a 24 so the mountains get closer and the lines are very straight. It’s just wonderful.

I love IMAX and I know that they have new cameras.

LUBEZKI: I think they have the digital 3-D camera. That is so exciting and I’m dying to work with it.

I wanted to know in the future, have you already thought about trying to film a lot of stuff in IMAX?

LUBEZKI: Absolutely. I’ve always wanted to shoot something for IMAX, and even though this movie was not shot specifically for IMAX, the shows in IMAX are incredibly immersive, they are really, really, really powerful. Not just because of the size of the screen but because of the laser projector where you can actually show blacks for the first time in film history. It’s a very different experience for the audience.

I went to an IMAX presentation where they demonstrated the laser projection at the Hollywood Highland and it blew my mind with the blacks in the lower right corner and the upper right corner being the exact same. There was just no degradation of quality.

LUBEZKI: It’s the first time in film history that directors and cameramen have the chance of projecting black on the screen, and that’s very important because we will be able to do things very, very dark. They’ll look mushy and gray and immediately you gain four or five tones of grays that you couldn’t see before. So when we saw yesterday the movie in laser, you could see the dark areas of the wardrobe and all of the different colors that were there that we couldn’t show otherwise. It’s just beautiful.

I love Children of Men. When you think back on the making of that now, is there a day or two that you’ll always remember? What do you remember from the making of that?

LUBEZKI: I do remember the day we shot the car scene where the camera is inside the car moving in 360 and how exciting it was to achieve it after a couple of weeks of really feeling insecure and that maybe it was not gonna happen. And the power that shooting it in real time had when I saw it, it felt that you were right there with the characters and it feels claustrophobic and scary and I loved that moment.

It seems to me that with that moment, that scene was a game changer for you because from there, you have really explored much longer takes, pushing the boundaries of what you have done as a cinematographer prior to that, at least in my view.

LUBEZKI: I was always interested in exploring that. You just need to find the right project and also a director that wants to explore that. And obviously Cuarón since Y Tu Mamá También was exploring doing very long takes, there was the very long take in the bar when the kids start to drink with the girl and then they go and start dancing, that’s probably 5 minutes long or something like that. The other thing that I remember well is I did a movie called Meet Joe Black, and there was an accident at the beginning of the movie where the character of Brad Pitt gets killed in a traffic accident and I remember convincing Marty [Brest] instead of using his storyboards where there were tons of cuts with the car etc., to do it as a one shot where you see him going away and you see the car hitting him and he leaning the shot and so on, how powerful was that? And it’s not anything I created; real time has a tremendous power on film. It’s just another way to express.

I didn’t realize it, but I’ve always had an affinity for Meet Joe Black. I’ve always had a soft spot for it.

LUBEZKI: Check that shot.

I remember the shot, but it’s interesting because I didn’t realize that you had shot until years later, and maybe that’s one of the reasons why I’m like ‘this is really good looking movie’.

LUBEZKI: Well thank you.

Now it’s like well, this explains it. Now I understand.

LUBEZKI: Thank you, you’re very kind.