Even though he might not have the same brand name recognition as, say, Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese, there as few filmmakers who have had the impact on their medium as significant as Errol Morris. The documentary director essentially re-invented the form to suit his interests over a long career that includes such titles as Gates Of Heaven, The Thin Blue Line, The Fog Of War, and Fast, Cheap, & Out Of Control.

Morris developed technology that allowed his interview subjects to make eye-contact with the camera, shot in cinemascope, and used mixtures of re-enactments and stock footage to create gloriously cinematic montages never before seen in documentaries. Typically backed by a pulsating Philip Glass score, his documentaries are riveting cinema entirely of Morris’ own design and their effects are so striking that they’ve been copied so constantly and consistently over the years that Morris’ style has essentially become the contemporary documentary aesthetic in many cases.

Yet, even with so many other movies and documentary TV series aping the Errol Morris aesthetic, his work always stands alone. The style is distinct sure, but it’s Morris’ remarkable ability to find unique people and get them to open up in such surprising ways that makes his movies unforgettable. That’s certainly true of his latest movie The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography, which just screened at the New York Film Festival following a premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival in September. Morris’ style is more stripped down this time and his subject is a personal friend, but the results are no less impressive.

Elsa Dorfman is a remarkable photographer who began taking candid black and white photos in the 60s of her friends like Alan Ginsbourg and Bob Dylan. Then she found her true medium with massive life size Polaroid photographs. The images are almost hyper real in vibrancy and detail, but the poses are always disarmingly casual and dripping with personality. Dorfman’s work is extraordinary and sadly underappreciated, which this doc hopes to rectify. But more importantly, she emerges as a fascinating and immensely lovable character for Morris’ camera, with their amusing and drifting conversations covering not only her life and career, but themes of memory, aging, loss, life, and death. The B-Side is both a delightfully entertaining documentary about an intriguing character and a unique portrait of life bordering on the profound.

Collider recently got a chance to chat with Errol Morris about his latest film as well as the impact he’s had on documentaries, the increasing challenge of find his subjects, lawsuits, murderers, and an oddly revealing Oscar short that he once made about Donald Trump discussing Citizen Kane.

Collider: I noticed there was a photo of you and your family in a montage of postcards of Elsa’s work. How long have you known her?

Errol Morris: Twenty-five years, more or less. I used to live in New York City, then when my son was two years old we moved to Cambridge Massachusetts and we’ve been there ever since. My son is now twenty-nine years old, so we’ve been up there for a while. The first Polaroid she ever took of someone in my family was my son when he was about four years old.

How did your paths first cross?

Morris: She was well known. Certainly in the Boston area, she’s well known as a portrait photographer. My wife always wanted to meet her and then there was some benefit where she was taking pictures. I don’t remember anymore what it was for. But she went in with our son Hamilton and Elsa took this fabulous portrait.

I believe this is the first time that you’ve done a documentary about someone who you knew personally. Was there any trepidation about that on your part or did it make things any trickier for you? I wasn’t sure if perhaps part of your process was getting to know your subjects through the interviews you do on camera.

Morris: Certainly, it’s different than anything that I’ve done before simply because Elsa and her husband are close personal friends. They were going to be our son’s guardians if anything happened to either of us. But I spent one afternoon with Elsa in her garage and she started opening various flat file drawers, taking out Polaroids and telling me stories about them. I thought from that moment on that there was a movie here. A very simple kind of movie of Elsa telling stories.

Obviously you didn’t use your Interrotron (a technical set up Morris developed that puts his face on a monitor below his camera so that his interview subjects make eye contact with the camera in the final film) this time. Why was that?

Morris: I’ve been working on a six-part series for Netflix and I chose not to use the Interrotron for that as well. I find it interesting because the Interrotron and a lot of things that I’ve done with documentary - like the use of cinemascope ratio and how I edit has been endlessly copied. I see it everywhere.

Are you trying to get away from that stuff because it’s so common now?

Morris: Indeed. Yes. Been there, done that. Philip Glass once told me, “They can always copy what you’ve done, but they can’t copy what you’re going to do.” I like to think that one of things I’ve done with non-fiction since the very beginning is to find new ways of telling true stories. So this is no different. This uses a lens system, which I have used for years in various different ways, but I’ve never used it in the context of an interview. This is the very first time that I’ve done that. It’s a lens called The Revolution, so it allowed me to interview Elsa and actually operate the camera. Well one of the cameras, because there were four cameras there.

I was surprised over the course of the conversation how deep the film gets and the way it becomes a discussion of aging and time and memory. Was that something that you thought would be inherent to Elsa’s story when you started work on the film or something that developed over the course of your conversations?

Morris: I like to think that every movie emerges from the conversations. To the extent that if I know exactly what was going to be said, all of the themes that are going to be expressed or in some way covered, then it becomes boring. The idea is that you’re heading in someway into uncharted territory. You don’t know what you’re going to hear. But built into the very idea of photography is as Oliver Wendell Holmes said in the 19th century, “it’s a mirror with a memory.” Part of the mystery of any given photograph is the fact that it was taken at a certain time and in a certain place and time keeps moving on. A photograph might be a moment in time preserved, but the world continues to change around it.

So the fact that Polaroid had discontinued their film stock and effectively ended Elsa’s work in the process didn’t play into the motivation of exploring those ideas?

Morris: Well of course it did. It’s so much a part of the whole story. But yes, I think that rather than forcing those themes to emerge, they emerge naturally form telling these stories. Like her story of Ginsberg and how she met Alan Ginsberg and how she came to photograph him up to the point when we hear those phone messages essentially documenting Ginsberg’s last days and his death.

Her photographs are remarkable just to see in your film and I’d imagine in person they are even more striking. Why do you think she wasn’t more widely known?

Morris: It’s really hard to know why certain artists become famous and others don’t. It’s pretty clear that fame isn’t inextricably connected with merit (Laughs). There are artists who are very well known and many of us feel they should be less well known, while there are others who aren’t well known and many feel deserve more attention. Certainly for me, Elsa is one of those artists. I’ve always loved her work. I’ve loved her and her work is so much an expression of her. One of the reasons to make the film is to expose Elsa, hopefully, to a wider audience.

I found an article online from February announcing the movie, so it seems like you finished it remarkably quickly. Is that faster than most of your movies come together?

Morris: Yes, is the answer to that. It just came together. I suppose the film if I had continued to shoot it could have been longer, but it seemed like in any ways that I had succeeded. Im one simple way I think I’ve succeeded was capturing Elsa. There’s something about Elsa, her personality, and her work that I believe is there. We just had a screening of the film at the New York Film Festival and we brought the camera on stage, the 20X24, and Elsa took my picture and pictures of people in the audience. I said to Ken Jones after that it’s so much easier to make a movie about someone who is so likeable that you just want to get out of the way.

There’s something appropriate about the fact that the movie is something of a snap shot, even in the production.

Morris: Well, thank you.

I’m always amazed by the people who you find for your films and the way you’re able to get them to open up. Have you ever had anyone turn you down?

Morris: Yes, I’ve had people turn me down. Not all that many, but certainly it happens. And it happens I would say now more often simply because twenty to thirty years ago, who was making documentary films? Nobody. Well, relatively few people. It was an art form that had limited theatrical distribution, if any at all. Some television distribution, but relatively small audiences regardless. And in the intervening years it’s become more and more popular with a lot of people. There’s a line I love in Conan The Barbarian where someone says, “That used to be another snake cult, now I see it everywhere.” That’s certainly true of documentaries. I wouldn’t say it’s ubiquitous, but it’s become close to ubiquitous. It’s everywhere. There are many, many people. And there are many people competing for stories.

Has that ever been an issue for you, where you’re interested in making a movie about someone at the same time as another filmmaker and it becomes a competition?

Morris: Recently it’s become much to my surprise, something that does happen. For example, I used to get almost all of my stories, and it’s probably still true, from newspapers. Primarily from The New York Times. No one ever really thinks of The New York Times as a tabloid newspaper and it isn’t a tabloid newspaper. But there is a tabloid newspaper within The New York Times very, very often. I remember on page one of The New York Times the article about Fred Leuchter. The heading was “Can Capital Punishment Be Humane” and it was the story about an electric chair repairman and execution machine designer. And then buried in the back of the paper was the fact that Fred Leuchter had also been involved in holocaust denial. Maybe today I would call Fred Leuchter and there would be two or three other documentary filmmakers interested in his story simply because of the exposure. Appearing on the front page of the New York Times even given the state of papers today is still something that’s seen by a lot of people. But maybe it’s because of the oddity of the story. I probably wouldn’t have done it if it was just a story about an executioner or a holocaust denier, but the combination of the two elements was irresistible. So yeah, I find it strange that there are so many people out there now.

What did you think of the Documentary Now parody of The Thin Blue Line?

Morris: Well, I liked the whole idea that my work has become significant enough to be parodied. It’s a kind of honour. It’s a kind of honour when I see how many people are imitating the style of how I make films. Yeah, I think it’s an interesting phenomenon. If you told me thirty years ago that people would be parodying documentary films, I never would have believed it. It wasn’t clear that the films themselves even had an audience, let alone an audience for parodies of them.

In particular, the true crime documentary form has exploded exponentially.

Morris: Indeed it has. I’m asked unendingly to become involved in series involving true crime and as it so happens the Netflix series that I’m working on is about a true crime.

How’s that going? Is there an end date or are you still waiting for the story to develop?

Morris: We’re hoping to be finished early next year.

I’m assuming that you still don’t want to say which case you’re studying?

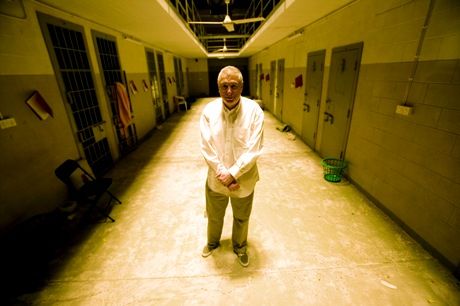

Morris: I don’t, but I can give you the title. Wormwood.

Are you still interested in exploring fiction as a filmmaker?

Morris: I am. In fact, part of the Netflix series is drama.

Interesting. Beyond re-enactment?

Morris: Beyond re-enactments. Why not invent something new?

I gather you’re writing a book about all of the murderers you’ve known?

Morris: I am. This will be my fourth book, actually. And yes, the title is The Murderers I’ve Known.

Does it concern you at all that you’ve known enough murderers to fill a book?

Morris: I worried there maybe weren’t enough actually. If anything I maybe should have talked to more murderers than the ones I did talk to.

There is something interesting about the fact that something about you has drawn in so many murderers in your lifetime, isn’t there?

Morris: Yes.

Do you have any thoughts on what that might be?

Morris: I started talking to murderers when I was really just out of the University Of Wisconsin in the early 70s.

Before the filmmaking, even?

Morris: Oh long, long, long before I became a filmmaker I was talking to killers. Filmmaking was an after thought.

So this is your real passion?

Morris: Maybe this is one of my real passions. Why deny it?

What ever happened with the lawsuit brought against you from Joyce McKinney from your movie Tabloid?

Morris: It was dismissed as a frivolous lawsuit that should never been brought.

Did that ever happen to you before?

Morris: Yes, actually from the person from The Thin Blue Line who I got off.

Really? I guess that’s just one of the risks of your job.

Morris: Yeah, well we live in a very litigious society. I’ve never sued anybody. I certainly can imagine a situation where I might sue, but it seems more or less in bad taste. But not suing others does not mean that others won’t sue you. If people are desperate enough to think that they can gain some kind of financial advantage, they’ll sue. In the case of The Thin Blue Line, I was surprised actually by many things. I was shooting down in Texas where the actual killer David Harris lived and I interviewed the town cop. He described these guys as being David Harris’ partners in crime and even though they had criminal records and had committed crimes, they sued me! More often than not, the insurance company that protects you against this type of lawsuit will settle it with cash and contest it in a court of law.

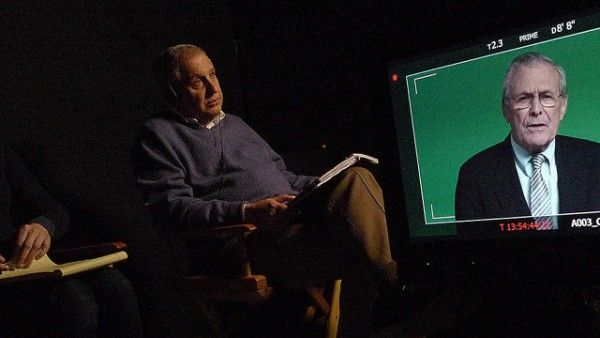

Speaking of suing people and bad taste, I always really enjoyed the short short interview that you did with Donald Trump about Citizen Kane. Even at the time it seemed so oddly revealing in ways that he clearly didn’t understand. Now it’s almost unbelievable.

Morris: I actually wanted to publish it in the New York Times, but the circumstances under which I did that movie made me vulnerable to a lawsuit and at this point in my career, I don’t want to go there. But it’s amazing. What is the moral that he takes away from Citizen Kane? I asked him if he had any advice for Charles Foster Kane and he said, “Yeah, get yourself a different woman.” What’s interesting is that Citizen Kane was meant as an anti-fascist/anti-capitalist melodrama and for Donald Trump it becomes just another kind of misogynistic claim that misses the point.

Was there anything from that interview that didn’t make it into that, but was compelling enough that you wish you had used it now?

Morris: There’s some more stuff, indeed. I’ve been involved in doing advertising for various elections and I just couldn’t see doing anti-Trump advertising in this election. My line has been, “How could you do anything worse that what he does himself?” You know, anything more negative, anything more disparaging, anything more adversarial than what he does already. The mystery is how he’s gotten as far as he’s gotten. The smarter people I know declined to watch the most recent debate. I unfortunately did. I actually felt diminished by watching it. If this is what discourse has become in America, who even wants to know about it? It’s just too demoralizing and unsettling.