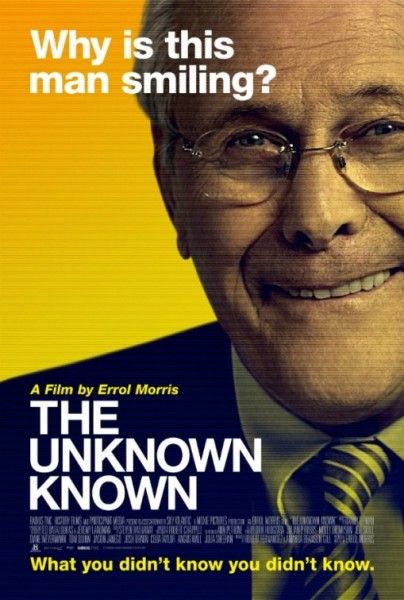

How does one interview perhaps the greatest interviewer of our time? Errol Morris, a titan of documentary filmmaking, has elicited introspective confessions from both a former US Secretary of Defense and a death-row inmate. He’s a man that can interview a self-avowed Holocaust denier (as he did with Fred Leuchter in Mr. Death) -- and somehow make you, the viewer, understand where this misguided man is coming from. In Morris’s latest, The Unknown Known, the great interviewer meets his match in the gobbledygook and aphorisms of two-time Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. The film (a sequel of sorts to Morris’s Academy Award winning The Fog of War) is pretty much just two men in a room – one asking questions, the other finding ways to shy away from answering. But this isn’t a film necessarily about Iraq or Abu Ghraib or any other political lightening-rod; instead it’s an expose of a man and how he wields/twists/misuses language to justify his means. A film that posits sometimes when you peel back the layers of a person, you discover the most horrible of truths: that there wasn’t anything there to begin with.

In the following interview with filmmaker Errol Morris, he discusses the ‘horrifying’ truth to Donald Rumsfeld, the perversion of language, the construction of false narratives, his own ‘physical’ presence in his documentaries, and going the fiction route for his next film Holland, Michigan. For the full Unknown Known interview, hit the jump.

Of note: Morris talks a bit about a series of articles he’s been writing for The New York Times in promotion of The Unknown Known. I’ve linked to them here. Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four. They, like the film itself, are well worth your time.

Collider: I've been reading the articles you've written for The New York Times. I was particularly struck by the second article you did where you trace the terminology of the 'Unknown Known', the 'Known Unknown' and all these phrases from John Keats where it's used as a declaration of love to ultimately Rumsfeld where it becomes an equivocation for WMDs. I'm interested when you use that sort of obfuscating language does that naturally lend itself to its own perversion?

ERROL MORRIS: I don’t know… Language can be used to so many diverse ends. It can be used to clarify and, of course, it can be used to obfuscate, confuse, evade... Orwell famously railed against the use of language that was meaningless in his essay [Politics and the English Language].

Then is the 'Unknown Known' a meaningless phrase?

MORRIS: You know -- I don't think it's a meaningless phrase. I think the problem with a lot of these phrases is that they are meaningful and the meaning is unclear. They can be interpreted in many different ways. The perfect example of this sort of thing is "Absence of Evidence isn't Evidence of Absence". Because it was first used -- and you'll see in the fourth part of the series in The New York Times -- it was used by astronomers, popularized by Carl Sagan. Is there extraterrestrial intelligent life somewhere else in the universe? And the argument is just because we have no direct evidence that doesn't provide proof it isn't there. So here you have one principle used in a very specific context and Donald Rumsfeld applies it to Iraq, where it means something very very different. The example I use in The New York Times is suppose someone looks for an elephant in a room. You open the door, you look inside, you don't see an elephant. You look under the bed, you look in the closets -- still no elephant. What do you conclude? Is absence of evidence not evidence of absence?

Going back to the film The Unknown Known, how did this come about? Did Rumsfeld approach you? Did you approach him or his people?

MORRIS: I approached Rumsfeld.

What was the process for getting him to agree to these interviews?

MORRIS: I was told by his lawyer that [Rumsfeld] would never agree to it. I sent him a letter and I sent him a copy of The Fog of War and he agreed to meet with me and we made this film.

Do you feel that The Fog of War and its depiction of Robert McNamara [U.S Secretary of Defense to JFK & Lyndon B. Johnson] influenced Rumsfeld's decision to participate in the documentary?

MORRIS: Certainly the success of that film did. I don't know whether he ever actually watched the picture. My guess is that he did not. He knew that it was a successful film and that I was considered a good filmmaker, that it was widely seen -- so yes I do feel that it influenced his decision.

On a purely technical level: how many interview sessions did you have with Rumsfeld and for over what period of time?

MORRIS: About a year. Eleven days. Over thirty hours.

When you're preparing questions, how important is the order in which you ask them? Do you try to ease the subject in or start with whatever's most pressing?

MORRIS: I don't work with a prepared list of questions.

Then what is your preparation process for these interviews?

MORRIS: Well I almost endlessly prepare but having prepared I don't have any fixed agenda, any list of questions or order of questions. In fact: when I was doing Standard Operating Procedure, a friend of mine and a journalist, Philip Gourevitch, sat in on many of the interviews. He asked me if I knew that the first thing I often said [to the interviewees] was 'I don't know where to start.' Usually that tends to be the case.

It's interesting because in the first New York Times article you wrote -- you have interviews with the White House Press Corp and they talk about how you have to be very careful in how to word your questions with Rumsfeld. Did you find that was the case when you were interviewing him?

MORRIS: The ingenuous answer would be 'yes'. Part of the difficulty in making this film is the goal isn't just to have Donald Rumsfeld get up and walk away. The goal is not to get into a fight. It's a very strange film. I wonder if people realize how strange it is. Often it's being judged as a standard political documentary. Let me put that slightly differently -- it's judged as if it should be a standard political documentary where I would interview ten to fifteen people about Donald Rumsfeld. Maybe I'd interview Donald Rumsfeld as well. But it's an external picture of the man. I wanted something radically different. I wanted history from the inside out. I wanted to create a portrait of how Donald Rumsfeld sees himself and wants to be seen by others in the belief that by doing so I could learn something unexpected and something of interest.

What would you say that you learned that was 'unexpected'?

MORRIS: I learned that somehow when asked to actually give a meaningful account of some of the most important events in history, events in which he was involved, that there was so very very little there. Almost as if he had never really thought deeply about any of them.

Is that frustrating as an interviewer?

MORRIS: It's frustrating -- but it's also... I find it really interesting, horrifying I suppose would be the correct word, that one would think there has to be some kind of reflection or insight being hidden; but I came to believe there was not. When Pam Hess [a member of the White House Corp], who I believe is the first person [I interview] in that four-part New York Times essay, says, “That's it. There's nothing more.” I believe that she's right. It's not as if there’s something there that I failed to reveal. It's that I revealed that there's nothing hidden.

So many of your films deal with the construction of false narratives. Tabloid, The Thin Blue Line and in this film, Rumsfeld is trying to construct his own false narrative. What is it about these false narratives that interest you?

MORRIS: I'm really interested in self-deception. Really interested in how people live in bubble universes. How people can fail to see the seemingly obvious. Rumsfeld may be the most clueless person I have ever interviewed. Was that a surprise? Yes -- I'm still surprised by it. I'm still in a state of disbelief about my own movie.

Has Rumsfeld seen the documentary? Has he approached you about the film's reception?

MORRIS: He's seen it. We really haven't talked since it first opened. He's seen many cuts of it. He's seen at least four different cuts of the movie.

And he's never told you what his opinion was on it?

MORRIS: He did. I've been the recipient of a number of Donald Rumsfeld ‘snowflakes’ [i.e. memos]. Detailed critiques of what he liked and didn't like in any of the cuts. But he had no control over the movie. I had final cut.

Speaking of those memos -- how did it become the framing device of the picture? When did you decide that in the editing process?

MORRIS: Very early on because it seemed if you're making a movie about how Donald Rumsfeld sees himself, what better source of access could you find than these memos he's written over the past ten, twenty or so years.

What is the editing process like between you and your editor Steven Hathaway?

MORRIS: It's really hard to know what the process is when you're starting with a mass of material where there is no specific storyline to begin with other than the fact that it’s dealing with a biography of this man. It's one of the reasons why I'm making a fiction film next because non-fiction is really so incredibly difficult to make.

Often times the only physical presence you have in your documentaries is your voice. How do you decide when to interject yourself, your voice, into your own documentaries?

MORRIS: Well there's no algorithm. It's always a struggle to figure out what you can include and what you have to exclude. The one thing you know going into something like this is almost everything is going to be excluded. There's just only so much you can put into whatever the length is. In the end, you know more stuff will end up on the editing room floor than included in the film.

It seems like in this film, your voice is more present than I think in any other film that I've seen of yours. Is that just a necessity of Donald Rumsfeld being such a difficult interview?

MORRIS: That certainly may be part of it but I think I'm moving in the direction of putting myself more into my movies. I've decided more or less that if I make another documentary then I'm actually going to put myself in it as a physical presence and not just simply a voice.

What do you feel like is the proper role for a documentarian in his/her films?

MORRIS: There is no proper role. There is no rule about how to make documentaries. The only rule, if you want to call it a rule at all, is you should be pursuing the truth. How you pursue it -- there is no one way to investigate a story or to present a story or to think about a story. You do the best you can. One of the fascinating things about documentary is that if you were to do a taxonomy of documentary, you would come up with dozens of different kinds of documentaries. Diary films, narrated historical slide shows, movies where the documentarian is actually present in most every frame, others where the documentarian is absent. And it goes on and on and on. It's what I like most about the genre. Every time you make one, you get to reinvent the form.

You mentioned you're doing a narrative film next -- Holland, Michigan what was the impetus for deciding to do a narrative film as your next picture?

MORRIS: I've always like narrative. I work with actors all the time. I've directed over a thousand television commercials. My most recent campaign for Taco Bell* has been written about more than my Rumsfeld documentary. So -- I'm a storyteller. I'm a person who tells stories with a camera. I'll fess up… I'll continue to make documentaries. I've been very fortunate. I've been writing. I've published a number of books. I have a third book coming out. I get to do a whole variety of things to do with filmmaking from commercials to documentaries to now some dramatic features... so why not?

The Unknown Know opens in select theaters April 4th.

*As Morris mentions: he’s directed over a thousand commercials. Here’s a link to his most recent Taco Bell ad.