From creator/showrunner Ronald D. Moore (Outlander, Battlestar Galactica), For All Mankind will debut exclusively on the new video subscription service Apple TV+, which will feature original shows, movies and documentaries, when it launches this fall through the Apple TV app. The 10-episode, hour-long highly anticipated drama series explores what would have happened, if the USSR beat the US to the moon and the global space race never ended, placing NASA astronauts, engineers and their families at the center of a fascinating alternate history timeline. The series stars Joel Kinnaman, Michael Dorman, Sarah Jones, Shantel VanSanten, Wrenn Schmidt and Jodi Balfour, and features a number of real historical figures from the era.

With the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 approaching on July 20th, executive producer/writer Ronald D. Moore took part in a conference call, along with NASA flight director Gerry Griffin and engineer and former NASA astronaut Garrett Reisman (who both serve as technical advisors on the series), to talk to some outlets about the upcoming TV series. During the interview, they discussed how this ended up as an alternative history story, keeping things as accurate as possible to the time period, what brought this series to the Apple TV+ streaming service, the characters at the center of this story, how deeply they get into the Soviet side of the story, the biggest production challenges in recreating this era, why they weren’t able to get direct approval from NASA, and whether they’re looking to continue telling this story in future seasons.

Question: Alternative history stories exist in contemporary pop culture, from The Man in the High Castle to The Watchmen, and just about anything by Harry Turtledove. Ron, what pulled you into this sub-genre?

RONALD D. MOORE: It was a couple of things. One was just my own personal interest in and passion for the subject. I grew up with the Apollo program, as a kid, and it was really the catalyst for inspiring me to become interested in science fiction, overall. So, it was very important, in my personal life. And when I was growing up, watching the space program in the ‘70s, I thought it was gonna go places. I thought it was gonna go much bigger than it did. I had dreams of moon bases and colonization, and all kinds of things that never came to pass. The idea of doing the history that I never got to see was personally really exciting and interesting to me. And then, on a creative level, separate from that, it was also interesting, in the concept of this particular show, to start at the beginning. The Man in the High Castle, and a lot of alternate history pieces, typically throw you into that existing world. On High Castle, the Nazis have already won, the Japanese have already won, and you’re in this other world. This was an opportunity to see it start and see how it developed. And also, the other difference for me is that this particular piece is very aspirational. It’s a very positive idea of a better world that could come about from an alternate history piece. Alternate history, not always, but tends to go to the dark and the dystopian. Terrible things happen and awful things have taken place, and the alternate world is a very dark and brooding one. Ours is going in the opposite direction. It’s a very positive one. It’s like, “Wow, by expanding the space racing and stepping strongly into the universe, the world became a better place, and the nation became a better place.” It’s a very optimistic sort of idea for an alternate history piece.

We’re about to mark the 50th anniversary of the moon landing on July 20, 1969. Can you talk about making your departure point from what actually happened? When does the first Soviet moon landing happen, in your universe, and how important was it to present what does stay the same as an accurate look at what we know from history?

MOORE: First of all, it’s important to note that the idea for the Russians to beat us the moon in this piece actually came from a conversation I had with Garrett [Reisman]. Garrett and I were having lunch, and I was picking his brain about ways of doing this. How and why would the space race have continued? That was the premise that I was starting with. What would be the impetus for the space race to continue beyond Apollo 17? And he said, “Well, you don’t realize how close to the Russians came to getting to the moon.” I said, “Really? I didn’t really know that they even tried.” He said, Oh, yeah!” I was fascinated with that concept. So, as we started doing our research for the show, and going back to figure out where the pivot point, or the butterfly effect moment would be, I held onto the idea that the chief designer of the Soviet program, Sergei Korolev, died on the table during a surgery in Moscow that different sources say different things about, but it seems like it was a botched surgery for some gastrointestinal problem. He died and, as a result, the Soviet program was really never the same. The rocket that they had designed for their moon attempt literally never really got off the ground and had explosions. So, our deeper premise, even though it’s not really stated in our pilot episode, is that Korolev lives. He survived the surgery and kept the Soviet program together, and was able to solve the design flaws in the rocket. He accelerated the program and had enough juice to keep the whole bureaucracy together and the funding going, and that’s when it all changed. For our story, we fade in on the Soviet landing on the moon, and it takes place about two weeks prior to Apollo 11, and the United States is just shocked because the Soviets came out of nowhere and grabbed the prize, right out from under our noses, at the last second.

GERRY GRIFFIN: I was actually called in to really take a look at the mission control aspects and the displays and the realness, and talk to the actors that were going to play the ground piece of this. The mission control set was really, really good. In fact, when I walked into it, I felt like I ‘d walked into the control center in Houston. And then, I got spent quite a bit of time with the actors and talked about how we did certain things, and I could tell they were soaking it up, like a sponge, and that they were gonna do a great job. I haven’t seen the first episode yet, but I know it’s gonna be good. It’s gonna be extremely realistic and keep in good stead with what would have been done. No matter what the alternate history path might take, it’s gonna look very accurate.

GARRETT REISMAN: From that very first lunch that I had with Ron, over at Space X, when he voiced the idea of, “Hey, what if we have an alternate history, where the Russians actually get there ahead of Apollo 11?,” my eyes lit up and I thought, “Wow, that is such a great premise for a show. That could be really, really entertaining.” I loved it. I actually really fell in love with the premise, right there, on the spot. And then, getting a chance to work on this has been a really awesome experience for me, personally. What’s really fantastic is how much everybody is really passionate about getting the details correct and the technical parts of it correct. At the same time, I’ve been trying very hard to not let any the truth get in the way of a good story. One of the things I’m very cognizant about is that what’s gonna make this show resonate with people is the story and the characters, and not necessarily whether they have the right instrument panel configuration, or whatever. At the same time, it’s really fun when we try to do both. We try to get it right, make sure the story is preserved and strong. Doing both, at the same time, is what makes it really interesting for me. When you watch the show, hopefully it feels real and everything seems like it’s the way it should be, but at the same time, I hope everybody’s really, really entertained.

With all of the new streaming services, why did you want to bring this show to Apple TV+, in particular?

MOORE: It actually goes to my personal relationship with Zack Van Amburg, who is now one of the co-presidents at Apple TV+. Zack had been one of the co-presidents at Sony Television for many years, and I’ve had a deal with Sony for a long time. He and I had briefly talked about doing a show set at NASA in the ‘70s, around the Skylab era, about many years ago, and it never really got off the ground, so we didn’t talk about it much further. And then, when he went to Apple a couple of years ago, soon after he had taken up his job there, he just called me over to see the new offices and have a general chat. I came over and, in the middle of that conversation, he was like, “You know, I still think about that idea about NASA in the ‘70s. What do you think about doing a Mad Men at NASA?” I said, “Oh, that would be really interesting.” He said, “Think about that.” And as I thought about it, I thought to myself, “You could certainly do that show, and that’s a great show, on some level, where you do a very character-oriented piece that is really about the people in and around the office complex of NASA.” But the larger story of the space program, in my opinion, was depressing because, in the ‘70s there was a history of budget cutbacks and of the ambitions being pulled back, smaller and smaller. In the beginning, they had hopes to go to Mars, and they had hopes for moon bases and various space systems. Essentially, it all got paired down and whittled down. They canceled Apollo 18, 19 and 20, they only did one Skylab instead of two, they canceled Mars altogether, and they focused everything on the space shuttle. I quickly said to Zack that the more exciting thing to me was to do the space program that I felt we were promised, but never got. That’s how the journey to the alternate history version was born, and it’s at Apple because it came out of our personal relationship.

How many episodes will make up this season?

MOORE: It’s 10 episodes, and each episode is an hour long.

What kind of budget did Apple let you play with?

MOORE: A healthy one. It’s not Game of Thrones money, but it’s a healthy budget.

Can you talk about the characters at the center of this story and the casting process you went through for this?

MOORE: We tried to focus the show on both astronauts and people in and around mission control and the Johnson Space Center. It’s a mixture of the people in front of the camera and behind the camera, if you want to think about it in those terms. Two of our characters are Ed Baldwin (Joel Kinnaman) and Gordo Stevens (Michael Dorman), who are astronauts that, in our version of the world, were originally on Apollo 10, and then they come to the forefront. As the story develops, over the first few episodes, they’re our primary astronauts. We also have characters like Neil Armstrong (Jeff Branson) and Buzz Aldrin (Chris Agos) and Deke Slayton (Chris Bauer), who are real historical figures, and they’re in the show, as well. And then, we have characters like Ed’s wife, Karen (Shantel VanSanten), and Gordo’s wife, Tracy (Sarah Jones). Tracy takes an interesting path that I won’t really get into, but essentially she’s going to become an astronaut, through an interesting story that’s unexpected, but at the same time, rooted in some real historical figures that were spouses of astronauts in the program, who were pilots, in their own right. We also have Gene Kranz, who’s another character that was a real historical figure, as a flight director in mission control. The casting process was thorough and it took quite awhile to find the right balance of people. It was really important to us that while Joel Kinnaman, who plays Ed Baldwin, is clearly the lead in the series, it’s very much an ensemble piece. It’s very much about all of the characters’ lives – their home lives and their professional lives. The nature of the series is that it will expand and continue going in a lot of different directions, so we needed a cast where you felt the chemistry, overall, was gonna work, in the long term. In certain episodes, we’ll emphasize certain characters or character pairings, and then in the next episode, they might recede into the background and bring others forward. We’ll keep that interesting rhythm going, where you’re never following just one person’s story through it all. It will be many threads in a very large, evolving tapestry of players. So, it was an interesting jigsaw puzzle to put together. We had to feel like all of these different characters, and all of these different actors and actresses, were gonna form something greater than the sum of the parts. That was the task in front of us.

Do you have a release date for the series?

MOORE: We don’t have a release date yet. Apple has just said that it’s gonna be in the fall. Honestly, that’s as much as I know.

Since a chunk of your audience is going to be people who were not alive for Apollo or the space race, how are you handling distinguishing and informing them about what was real and where the story departs?

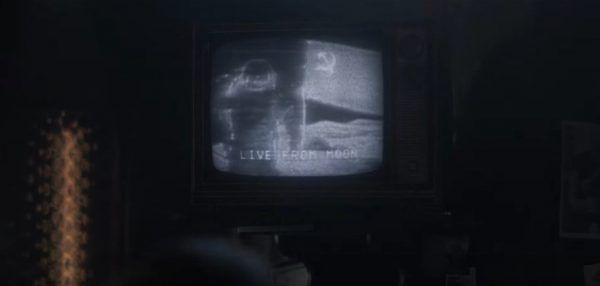

MOORE: I believe the story can exist without knowing the history. As long as the audience knows that the Russians didn’t get there first, that’s the big thing. Maybe there’s a percentage of the population that is unaware of that, sad but true, but whatever. You need to know that Neil Armstrong, an American, was the first man on the moon. As long as you know that, just go with us for the ride. It’s the kind of show that should peak your interest about what’s real and what’s not. Most people probably know that there weren’t women in a space program, until much later. I think that they know certain things didn’t happen. We don’t have a moon base. So, by and large, even people who have only the most surface knowledge of the space program will get that this is a very different history than what really happened. And for other people who do know history, there’ll be all kinds of fascinating tidbits, some of them big, some of them background, almost Easter egg details of things happening on television sets, and references to historical, political and cultural events, that are slightly different in our world, or radically different in our world. I think people will be motivated to probably go look up some of those things online. We talked with Apple, during the development of the show, about how, at some point in the future, there might be resources where a viewer can dive deeper into some of these topics. I’m not sure how much of that will be available at the beginning or later because it’s still just a general talking point between us, but Apple does want the ability, eventually, for viewers to be able to do a deep dive into the background of the historical facts versus the historical fiction of the show. But even if you’re not a history buff, or you’re not interested in history, the character story and the story itself is strong enough to pull you in, and you’ll feel that you’re watching something real. That was really important to us. That’s why we had Garrett and Gerry come in, and we spent a lot of time and research, not just on the technical aspects of the show, but also on the reality of life, in and around NASA and the world, in 1969 and the early ‘70s, to really portray that as authentically as we can, even as we’re making changes within that. We just want the audience to always believe that this is really happening, this is real, and this is all plausible.

Are you relying on recreated sets, or are you adapting archival footage?

MOORE: We do have some archival footage. I don’t think we’ve altered archival footage, per se. I think we’ve cleaned up some archival shots. I don’t know if we’ve actually altered any of that. I think we’ve used them as real shots, and then created our own versions of other shots. Maybe we made some minor alteration, or did something for a particular angle, but by and large, we’ve pretty much either created our own or used existing footage.

What were the biggest production challenges, in recreating this era?

MOORE: Physically shooting it, the challenge of recreating a bygone era is no easy task, tracking down all of those different switches and displays. One thing that I can tell you, that was interesting and news to me, is that trying to get TV sets from the period was a nightmare. It’s really, really hard to find period CRTs now. The actual tube has vanished. It’s become a collector’s item. Billions of them once walked the earth and now, like the dinosaurs, they’re extinct. They live all in boneyards or museums or in people’s private collections, and this is a world where we’re supposed to have television sets in everyone’s living room, and all of the monitor screens in mission control were CRTs. It was crazy. You couldn’t find them. So, we ended up having to cheat a lot of them, where we’d have a flat screen, and then we’d have to put a piece of curved beveled plastic or glass over it, to simulate the look and feel of a CRT, which was madness. I couldn’t believe that we were unable to find television screens, of all things, in 2019.

How did you do the shots inside of the spacecraft, and was it particularly difficult to recreate environment suits, from the time?

MOORE: The interior of the spacecraft during weightlessness is a challenge. We used a variety of tricks – everything from wires to gimbals to teeter totters, and all of the tricks that other movies and TV shows have done. Apollo 13 really did it. We didn’t do the vomit comet and send them up in a plane with a camera crew. That was beyond our means, so we had to do everything on the set. There’s a company, called Global Effects, which rents the space suits. They had the exact replicas of the Apollo suits, but they’re difficult to work with. They’re not easy. They’re complicated for the actors to get in and out of. They tend to get a little hot, even though they have their own internal cooling on them. There’s only so many of them, and they’re expensive. So, the suits were definitely an issue. We had to learn what it took to do it, and then plan ahead. We had to practice doing that hop that they would do on the moon. It took time and effort to figure out exactly how to replicate that on our soundstages. It was a big technical challenge.

REISMAN: It’s hard to get that stuff right. I didn’t quite appreciate how hard it was going to be to get it all right, especially the weightlessness. What’s interesting is that, of course, we have a lot of shots in one-G on the Earth, but we also have a lot of shots in space, where it’s micro-gravity or zero gravity, and we also have the moon, where it’s one-sixth of Earth’s gravity. Getting all of the physics right, in all those shots, and getting tethers to not just fall down in one-G, but to simulate like they’re floating in zero-G, was really challenging. We were constantly fixing things or changing things to make it better. Everybody was really dedicated to getting it right, which made my job really fun, but that’s hard. For me, personally, the other thing that was challenging was, I flew in the space shuttle and this first season is set in the Apollo era, and it was a real education for me in remembering. Fortunately, a lot of it is very similar. We borrowed heavily from the architecture of Apollo. It was really neat to study another spacecraft that I never got to fly. It felt like I was back in training again, actually.

In the trailer, the NASA emblem has one significant change, with the vector pointing the other direction. Is that your way of illustrating that it’s a different world, or is that an issue with NASA?

MOORE: It wasn’t really an issue with NASA. It’s just that NASA has a policy, that we respect, that they will lend their support and the use of their emblems, if the show or the movie that you’re doing is portraying the events of the space program, exactly as they really happened. I think that comes out of the fact that there’s been so much crap out there about how the moon landings were fake and it’s all a hoax. At some point sort, NASA instituted a policy of, “If we’re gonna literally put our seal of approval on something, we want it to be something that was really true.” I believe they were very sympathetic, and they were intrigued about what we were doing, and they’re not against what we’re doing, but it’s just a policy of theirs, not too to put their emblem and, by implication, their stamp of approval on something that wasn’t actually historically accurate.

REISMAN: That’s right. We sent them a treatment and tried to get approval because we would have loved to have had more support from NASA, but that whole office, with the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 upon us, was overwhelmed. I think the thought of having to deal with a show that goes to some very important, iconic moments in history, and then alters them, was a bit much for what they were able to commit to, resource wise, at this time, so they weren’t ready to throw their weight and support behind what we were doing. I think they sent the treatment to some of the historians, and it blew them away. That didn’t help us that much with getting their support, but in the end, we were able to make it all work out.

GERRY: This is not a unique problem with For All Mankind. Everything the agency is doing is getting closer scrutiny. It’s not as easy as it was, 10 years ago, to get NASA approval. They have really stiffened that policy. The guy that looks that stuff over at headquarters is becoming more and more unwilling to make exceptions. So, it’s not unique. They’re probably going to be that way, the rest of their lives.

When it comes to the technological aspect and the scientific portion of the series, how accurate to history is that, or do you deviate from the technology that was around, at that time, for the purpose of the story? at all? Um, from the technology that was around at that time for the purpose of the story?

MOORE: For Season 1, we start with the base of what really was there, in 1969, and we start with the reality of the Apollo program, the Apollo spacecraft, and the Saturn V. And then, we move forward. Even when we get to the moon base, which we based, essentially, on re-purposing what was going to be Skylab, in our version of events. Our production designers started with, “Okay, if they had tried to convert what was going to be Skylab into a moon base, would it be like?” He did it in exacting detail. It’s all based in the real technology.

REISMAN: That was definitely the jumping off point and, in the first couple of episodes, you’ll see that it’s very true to the real technology of the day, with the instrument panels, the consoles in mission control, and even the documents. If you look closely, the things hanging on the wall are all very authentic. Even with the switch positions and the controls in the spacecraft, as the actors go about their astronaut duties, we tried to make sure that they’re actually using and doing the right things in the Apollo command and service module, at that time. One of the premises of the whole show is that, as a result of all of the investment in space transportation technologies that comes from the continuing of the program, technology, as a whole, advances more rapidly that it did, in reality. As the season goes on, you start seeing modifications and things that show up before their time, but that’s on purpose, predicated on an accelerated development of technology. So, you’ll start seeing it deviate from reality, and those are Easter eggs.

Garrett and Gerry, as people that worked at NASA and as experts in the field, how important is it to you that those details remain historically accurate? Do you mind that it deviates, in that sense?

GRIFFIN: There’s always some that will say, “That didn’t really happen,” or “It didn’t look that way, or act that way.” But for the most part, people will understand that this is an alternate history piece. During the Apollo program, we didn’t think much about the Soviet Union. It was like two baseball or football teams playing. We had to worry about our own team, and not about what they were doing. We were really focused on the goal of getting to the moon first. That was our driving force. It was not the fact that we were in a race, particularly with the Soviet Union. It was just that the president said, “Let’s go. Let’s get there, in this decade.” That’s what our goal was. And so, I think this alternate history piece will be an interesting thought because we never thought about losing. We thought we were gonna beat them. You don’t go into a race like that, unless you think you’ve got a chance of winning it, and we all did. We were all young enough that we didn’t know we couldn’t do it, so we just did it. But at the end of the day, I think this is gonna be a very entertaining thing to think about. It got me thinking, “What would have happened, had they gotten there first?” I don’t know what would’ve happened. I think this story will be a very likely outcome. Who knows? Maybe this is what would have happened.

REISMAN: One of the really fun parts for me is that I really hope that those of our viewers who are real space buffs, and who are really knowledgeable about the technology and the history come away saying, “Well, that didn’t happen, but it could have.” I really hope that’s the reaction that they have.

MOORE: We never took it upon ourselves to say, “This is what would have happened,” ‘cause you can never know. The premise was always that this could have happened, and we try to support that, to make it plausible. That’s why we went to the level of detail and authenticity that we strove for. We want you to be able to say, “This could have happened because this existed, and this could have led to that.” We wanted to have a very logical chain of events and a chain of thought that would allow these things to happen, so that you can really build on the basic believability of the show. Whatever technical or a detail mistakes there might be, and I’m sure, for all of our work, there’s gonna be the moment where somebody flips the wrong switch, or looks the wrong direction, or some diagram in the background is wrong, you can blame me for all of that. The technical consultants always give us the truth. They were always on it, and they were always pointing out the details, from script through production an into post-production. Garrett has come into our editing room and sat with us, and looked at pieces of film, and helped us correct dialogue that’s off-camera, or changed the physics of a spacecraft in motion and space. It’s not that these guys didn’t give us the right information. If there’s mistakes, I’m the showrunner and it’s my responsibility, so you can direct those cards and letters and emails towards me, and not them.

Beyond knowing that the Russians were the first on the moon, how much of the Soviet space program do you explore, in this first season? Do you follow how they advance, in addition to how the United States advances?

MOORE: We do, but we pretty much tell it from the point of view of the people at NASA and the American public. Remember that the Soviet program of that area was notoriously secretive. They were hiding all kinds of things. They wouldn’t even tell you when certain missions were happening, until we were underway. So, we tell that story from our point of view. You don’t really get inside how they’re doing it or why, or what their decisions are. We cobbled together the Soviet program from what the historical record left us. If we were showing things of the Soviet program, we tried to make them as historically accurate as we were able to, but for the most part, we play it as the competitors over the horizon, and you’re not sure what they’re gonna do next. And then, all of a sudden, they do something, and we have to figure out what they did and how they got there. After the first moon landing, are they trying to build their own moon base, and what would that be at? You play it mysterious and like you’re never quite sure what they’re going to do next. Are we ahead, or are we behind? That was how we played Season 1.

Some historians attribute the landing as the first bringing down of the Soviet Union, later in the ‘80s. Do explore any of the socio-politics of what happens when a Soviet Russia succeeds and what that means to the United States in a Cold War?

MOORE: We do, actually, and we take the opposite approach from what happened, historically. We say, “Well, if they had gotten there first and they had done it by surprise, in this bold from the blue moment, it would’ve shocked the world and it would would’ve enormously increased their prestige and their popularity, and it would’ve shifted the whole idea of the Soviet Union and where they were in the Cold War, and they would take so much glory and prestige from that, that they would start building on it, and they, too, would continue the space race.” We have references in the show to cultural and socio-political things happening outside the walls of NASA, as a result. The way the Nixon administration reacts to it is one big thing. There’s a scene where we have an astronaut wife, who’s just coming back from Europe, and she’s talking to some other people about how there were some kids walking around with hammer and sickle t-shirts on and she couldn’t believe it. We’re playing the whole idea that it shifted the goal post and the direction of the Cold War, as a result of this.

How much freedom did you guys have with your storytelling, when it came to working with Apple TV+? Were there any like limitations?

MOORE: It was pretty loose. The nature of the show was such that I didn’t need to push a lot of creative boundaries. It’s not a show that’s about graphic content, or violence or sex. I didn’t have any of that, as part of what we were doing. It just wasn’t an issue for me, in general. It felt like a very loose, creative environment. I was pretty much able to tell the story, in the way that I wanted to tell it. I never ran into barriers. That’s all I really know about it.

Are you looking to do further seasons, after these 10 episodes?

MOORE: We are definitely talking about a second season, at this point. We’re starting to get together stories and possible scripts. Apple hasn’t picked us up officially, but we’re definitely in talks already, moving ahead with planning, in case they do.

For All Mankind will be available to stream later this year at Apple TV+.