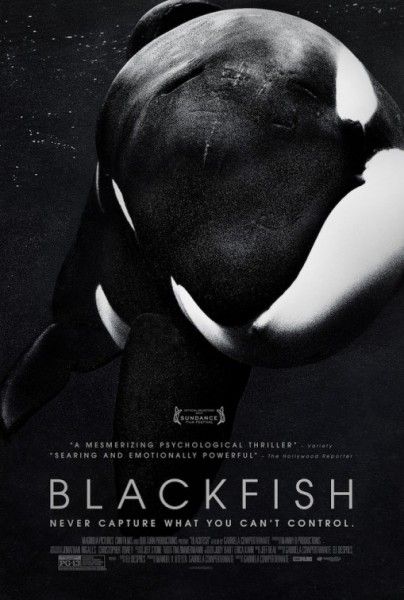

In her new documentary, Blackfish, opening July 19th, filmmaker Gabriela Cowperthwaite uses the story of a notorious performing whale, riveting interviews and never before seen footage to reveal the devastating consequences of keeping intelligent, sentient creatures in captivity. February 24, 2010 is a day whale trainers and fans of sea parks will never forget when veteran killer whale trainer Dawn Brancheau was brutally attacked and killed at SeaWorld Orlando by one of the park’s oldest residents, an orca names Tilikum. Her death became the catalyst for former SeaWorld trainers Jeffrey Ventre, Samantha Berg, Dean Gomersall, Carol Ray, Kim Ashdown and John Hargrove to speak out.

During my recent interview, Cowperthwaite and Ventre talked about what led them to tackle this subject, how the film’s financing came together, the challenge of making it without SeaWorld’s participation, how the trainers’ perspectives changed over time as they became disillusioned, why they became more vocal about what they had seen after Brancheau’s death, how SeaWorld’s public relations spin concerning her death differed significantly from their legal story, the decision not to include some of the more graphic footage in the documentary, and why the fight against animal exploitation should be a top priority. Hit the jump to read the interview.

Collider: Can you talk about the genesis of this film and what made you want to tackle this subject?

Gabriela Cowperthwaite: I started making the film because I had a question. I didn’t understand why a top SeaWorld trainer came to be killed by a killer whale at SeaWorld. In my mind, that didn’t square with the lay information that I had about killer whales which was that they’re highly intelligent and that they generally get along with human beings. I just didn’t think they did that to us. I thought they were our friends here on this planet. I was confused by it. I began figuring out what happened on that day and that caused me to start peeling back the onion and understanding there was a much bigger story that sat beneath the surface.

Jeff, was there any particular incident when you were a trainer that changed your perspective on what you were doing with the killer whales?

Jeffrey Ventre: I was at SeaWorld for eight years. I did two tours of duty at Shamu Stadium which is the killer whale stadium. When I first got hired, I would say it was about a one to five percent chance of getting hired. If you got an interview, then you took a swim test and you were in a honeymoon period with the park. I spent my first year at Shamu Stadium happily scrubbing buckets and doing show lines, and then I got moved away to the whale and dolphin stadium for about three years. Then, I came back to Shamu Stadium for the last part of my time there. When I came back the second time, I was much more armed with real-world knowledge of how killer whales live in the wild. I had been talking with Dr. Astrid van Ginneken who is a top researcher still to this day. She’s a co-principal investigator for Orca Survey. I was armed with more real-world knowledge other than the PR spin that SeaWorld has been basically controlling for the last forty years. When I came back, the things that I noticed right off the bat were the collapsed dorsal fins, the broken teeth, the fact that these whales were generally deconditioned, a little fatter and plumper than the whales you see in the wild, and that they were getting regular medicines like antibiotics and sometimes stomach protectants to prevent ulcers from happening. We were pumping water into fish to get them the water that they need on a daily basis, because in the wild, wild fish are naturally more hydrated. The blood of the fish is actually mostly water. When you freeze and thaw fish out to feed to captive animals, it’s relatively dehydrated. The animals are in a relative state of constant dehydration in captivity. I had a biology background. I now work as a physician, and so these were questions that were always in my mind. I was able to make those observations only after time went by. It’s been an evolution for me, and for all the former trainers, because we bought into that mythology harder than anybody.

I found that to be the most interesting aspect about the film. I always assumed these trainers were marine biologists and professionals. Do you think SeaWorld makes a conscious effort to hire kids?

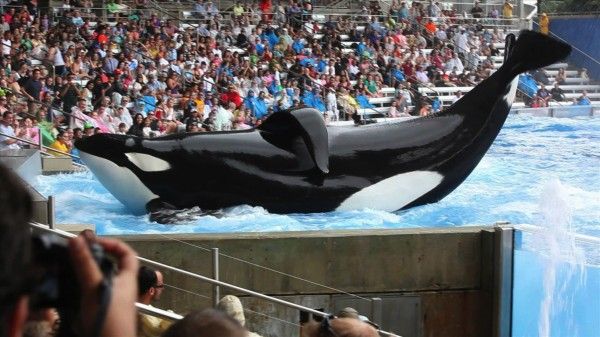

Ventre: You saw John Sillick get smashed between the two whales. That happened five days before I got hired. I know that after that fact, one of the beefs when they did the investigation was that they were paying these kids five dollars an hour. Most of them don’t have any college background. None of the management at SeaWorld went to college. I’m not saying college is necessary for everything, but you would think that there was a little science going on. And as Gabriela is fond of saying, when you peel back the onion, you see it’s just cowboys putting on a sea circus. And I use the term “circus” in an accurate way, not a way to belittle. I mean, this is a version of the Roman circus. It’s entertainment with lights and pop music and sprayers and jumping whales and photo opportunities. It’s not science that they’re doing there.

Gabriela, can you talk about how the financing for the film came together? How was it possible for you to make the film once you had the idea?

Cowperthwaite: It’s interesting. Having been someone who had heard about the incident, I wanted to use that as my portal to tell the story. I’m also a mother who took her kids to SeaWorld. I don’t come from any animal activism. I came in with no point of view just wanting to know why in the world this happened. I wrote a treatment when I figured out that there were a lot of questions that I had. Again, the treatment was so different than this film that I ended up creating because it started at such a different point. That treatment was what facilitated the funding to come in. I was introduced to two executive producers (Judy Bart and Erica Kahn) or investors who were interested in making their first film. They took a bunch of treatments and narrative fiction scripts and looked at everything, and then decided this was the one they would go with. I consider myself to be tremendously lucky. I mean, it’s just luck I found two people who maybe didn’t know any better than to go ahead and move forward with a documentary. They were really behind us and we just had those two sole financiers the entire time.

Was it a challenge to find so many trainers to talk about their experiences?

Cowperthwaite: A number of them, a handful of them, had become vocal after the Dawn Brancheau death. What they heard coming out of that park after that death didn’t sit well with them. It didn’t square with what they themselves had experienced at that park. They’re also established in their new careers and they have their new lives. Jeff is a medical doctor in Washington. They have each moved on from there, so they have a considerable amount of distance from their former employer and felt a bit more comfortable talking about a past life. That’s not the case with all the trainers. A couple of the trainers still experience the shadow of the employer, even though they’ve left, and they obviously had to leave before being interviewed for the film. It was much more uncomfortable for them, and I definitely had a couple people back out at the last minute because of their fears and a whole career of not feeling comfortable speaking out against their employer. That was what was looming over them and what continues to loom over them.

Jeff, was Dawn’s death one of the reasons why you wanted to participate in this documentary?

Ventre: I’ve said this before, but sometimes I almost feel like we entered the conversation by default. One thing that happened to me in particular, because I had studied wild killer whales after SeaWorld, was that I got a call from Anderson Cooper the day Dawn was killed. And so, I ended up being on that show (CNN’s 360). Even though the last time I had worked there was 1995, I was still scared to step forward. Dr. John Jett, another guy in the film, said, “You’ve got to say something.” Based on that first interview, then Wolf Blitzer called and then CBS called. So I ended up doing four national television interviews, and then both myself and Dr. Jett in the film were discovered by Tim Zimmermann because no one else would provide him [with information]. He’s a writer for Outside Magazine. He wrote a great piece called The Killer in the Pool.

Cowperthwaite: He’s associate producer on the film, too.

Ventre: He wrote this beautiful story that ended up getting Gabriela’s attention, because she had heard about it, too, the same way we all did. And so, Tim and the trainers started a little working group, pooling all of our knowledge together and putting it in one spot. That’s how Voice of the Orcas website started. It was basically a place to dump information. It was like, “We’ve got all this. Where are we going to put it? It’s not doing anybody any good by being on a piece of paper somewhere. Let’s get it online.” It built from that. That’s how I got involved. Of course, when Tim emailed the group, I met this great documentary filmmaker. I was introduced to Gabriela. We had already planned to go to what we call a “super pub.” We had been meeting in the San Juan Islands to see wild killer whales already, and Gabby leveraged that as a way to get a lot of interviews in one spot at one time. That was in the summer of 2011 and then we repeated filming in the summer of 2012. That’s how I got involved and most of the trainers in the film. John Hargrove came in a little bit later. He just quit last year in 2012.

Did you approach Keltie Byrne’s family or Dawn Brancheau’s family about being a part of the documentary? Did SeaWorld pay them to stay away? Did they not want to be involved?

Cowperthwaite: I never theorize on any of that stuff because I just don’t know anything. I don’t think any of us really know anything about her family’s participation in any legal stuff. The only thing I know for sure is that her family has fought very hard to keep the tape that shows her death out of the public eye, so that’s the extent of it. Originally, I did want very much for her family to be a voice in some way in the film. I actually thought that the film would be powerful if it in some way had Dawn’s voice in it. It was a very important lesson for me to understand that my need for this film meant that I would have to regurgitate the incident. I would have to regurgitate that fateful day for the documentary. And regurgitating that day is so out of step with healing for her family. They want to focus on Dawn and what she did in her life, not focus on her demise. So that’s a tough one, because I wanted to give them this film and understanding of why this came to happen and that she was this fantastic trainer and it wasn’t her fault. You think in your head you’re maybe giving someone a gift, and in fact, you’re not at all. They need you to go off to the side and live in a parallel universe. It was hard, but it was a great lesson for me.

Ventre: I have one little interesting caveat to the film that no one’s really talked about, but it even comes out in the film somewhat. It’s the paradoxical difference between the way SeaWorld talks about Dawn in the media in a public relations way and then the way they treated her legally. For example, “She’s our sister, our daughter. We’ve lost one of our cast members, the beloved Dawn Brancheau, one of the greatest trainers and the poster child for SeaWorld.” But yet, when they got into the courtroom, they were pinning it on her. That hasn’t really been discussed -- the legal story versus the public relations story. It’s pretty interesting how they were juggling that.

How difficult was it to make this film without the participation of SeaWorld?

Cowperthwaite: What’s interesting is I always thought in my head that in order to make a documentary like this, you needed to give five minutes to SeaWorld and five minutes to a critic of SeaWorld and follow this structural pattern. When I started realizing what it was that I had to reveal in this film, and that it was a lot of information that SeaWorld has fought very hard to keep from the public eye, I realized that I had a choice there. I had to decide that my structure was going to be to tell the truthful, fact-driven narrative from beginning to end, following Tilikum’s trajectory through the eyes of the former trainers, that I can just tell the truth and lay out the facts. Someone said that if you try too hard to do “on the one hand, but then on the other hand,” you may become faithless to the truth. And so, if I just promise myself that I would not sensationalize, not shoehorn information in there that will manipulate people into feeling things and stick to the fact-driven story, then that is a story that people need to hear. There was no question in my mind that that ended up by default having to be my structure. So yes, I was disappointed at first that they didn’t agree to be interviewed, and yet I also realized that they have essentially controlled the entire message for 40 years, that they are the message. We all believed in the happy Shamu icon and the happy Shamu image. They’ve controlled that message now for 40 years. Now can I take 80 minutes to just let the truth do some work here? I don’t ultimately feel it’s uneven. It is uneven in that we’re the one that’s the subversive voices and the dissent is the voices that need to begin coming out.

How were you able to gain access to some of the compelling footage you used in the film?

Cowperthwaite: Anything you could possibly imagine as a source, I tapped into, whether it’s local news, national news, people’s personal archives, people who may have filmed at a park. The only way you find that out is by just starting. You start a search and you ask people and they say, “I don’t necessarily have that footage, but I think I might have known someone who was there at the time.” And then, you just do this chain. Probably the hardest part of documentary filmmaking is persevering, knowing that someone had to be somewhere with a camera, and then going forth to secure rights and find out who owns it and all that. It’s longwinded for sure.

There is some graphic footage in the documentary. Was there additional footage that you didn’t show because it was too graphic?

Cowperthwaite: Specifically, the death of Dawn Brancheau tape. Again, the family has always fought very hard to keep that out of the public eye. I stood behind them in that. I knew when I began the film that I would never ever show that footage. To me, and Jeff has heard me say this a hundred times, I don’t believe there’s anything educational you could possibly get out of seeing that, that you couldn’t get from an autopsy report. In fact, it would be damaging and it could be so traumatic. I know I have to live with this film forever and I couldn’t have lived with that decision. I couldn’t have done that to the family. I also want children to be able to see this. I think that’s my most important audience in some ways. You can’t go in necessarily with all the weapons in your arsenal. You have to be careful.

An animal in a cage, on land, or in the water just doesn’t work. Where do we go from here?

Cowperthwaite: I know we’ll both answer this because we both feel very strongly about it. All of this surprised a lot of people, but none of us think that SeaWorld should shut its doors. It’s a two billion dollar a year industry. You’ve got to believe that an industry like that is probably one of the only places that has the financial resources to institute the kind of changes we would love to see and advocate for. Some of those are they could turn their parks into rehabilitation release centers where you can take care of an animal and then release it. There’s also the sea pen alternative, which is essentially cordoning off part of an ocean cove with a net, and you can semi-retire whales to that, and they’re actually feeling the natural rhythms of the ocean and can be killer whales for the first time. A lot of people think you can just put them in the open ocean and you can’t necessarily do that because they can’t eat live fish. They have antibiotics. Jeff was saying because they’re hopped up on that, they would probably soon after die. You could keep an eye on them and even charge money to bring people to come and see them. The lovely thing about that is people would actually be seeing a real killer whale doing what a killer whale can actually do, and it’s so much more inspiring and impossible than the silly, goofy tricks you’re seeing at the park. Those are some of the alternatives we’ve suggested.

Ventre: Don’t buy a ticket. SeaWorld needs to change its business model. Killer whales shouldn’t be in captivity, nor should cetaceans in general or anything that’s a free-ranging animal. Number one, don’t buy a ticket. It will force this big megalithic corporation to change its ways. Use animatronics, Pixar, whatever you want to educate people. Number two, captivity for killer whales has to end at some point globally, and it will, but unfortunately it’s going to be slow, and the whales that they have in captivity are going to take a while to die off. But we have no problem with them using this resource in whatever way they see fit, but let’s do it in a humane way. And number three, I think the future is going to be dictated in the court system and by the Nonhuman Rights Project. What I mean by that is, the way we got out of slavery at some point was when the distinction of what a black person was in the United States went from property to a person. So, some of these animals, whether it’s elephants or chimps or cetaceans, have demonstrated self-awareness. They grieve their young. They use tools and language. They have culture. At some point, in a court in the United States, a case is going to be won for a particular animal. And once that happens, it’s going to close the door at least in this country. Unfortunately, there are plenty of other places in the world like the Middle East and China where human rights, civil rights, aren’t what they are here. So I think Blackstone (private equity giant Blackstone Group) will dish whales off to those places at least for a while just because it’s such a profitable business. In fact, when SeaWorld did its IPO just a few months ago, there was a lot of interest from China and that was scary. It was like the Borg.

Gabriela, what are you working on next?

Cowperthwaite: I am working on something, but I made a solid promise to myself to never say anything about it, because it’s documentary karma that the moment you start talking about something, you’re not doing it. And, it’s only something when it’s something. Right now it’s in an embryonic stage, but I am working on something. I love the question. It makes me feel energized. Right now, we’re very concerned with getting this kid dressed for the winter and out the door properly. Once we do that, then I’ll feel comfortable talking about my other kids.

For more info on the film: http://blackfishmovie.com,