The Australian drama The Eye of the Storm, directed by Fred Schepisi and adapted from the novel by Nobel Prize winner Patrick White, tells the story of Elizabeth Hunter (Charlotte Rampling), as her son and daughter return home to convene at her deathbed. As Sir Basil (Geoffrey Rush), a famous but struggling actor in London, and Dorothy (Judy Davis), a broke French princess, attempt to reconcile with their formidable and tempestuous mother to ensure their inheritance, all Mrs. Hunter wants to do is choose when and how she will die.

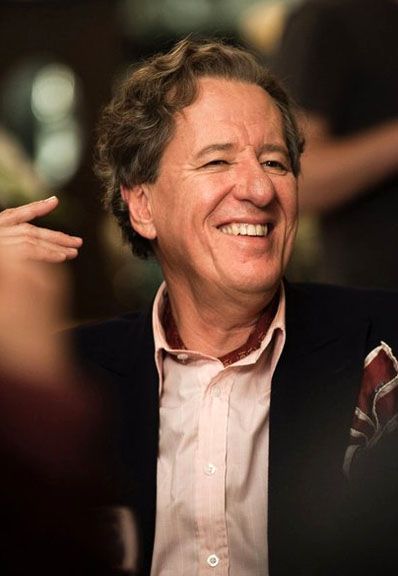

During this recent exclusive phone interview with Collider, Academy Award-winning actor Geoffrey Rush talked about how he came to be a part of The Eye of the Storm, why he wanted to work with director Fred Schepisi, how gratifying it is to get such great feedback from American audiences about the film, how he went about understanding this character, and the awkwardness of doing sex scenes with the director’s daughter, Alexandra Schepisi, who was his co-star. He also talked about the best part of being involved with the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise and that the script for the fifth film is currently in development, what attracts him to projects and roles now, and the film he just completed with Giuseppe Tornatore (Cinema Paradiso), called The Best Offer. Check out what he had to say after the jump.

Collider: How did you come to be a part of this film? Did the director just ask you to do the role?

GEOFFREY RUSH: I got to know (director) Fred Schepisi. Fred has always been a hero of mine. I was a student in London in the mid-‘70s, at a point where our Australian film industry had been dead in the water for close to five decades. And suddenly, when I was over there, I began to see this re-ignition of Australian filmmaking in a European context. I was watching it with French audiences and English audiences, and two of the first films I saw were The Devil’s Playground and The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, and I was just gobsmacked by how assured and deeply creative they were. Here was the excitement of a new voice from a country that no one associated with filmmaking. So, I got to meet Fred socially in Melbourne.

About 10 years ago, I became the patron of the Melbourne film industry, so I got to meet him at cocktail parties and film events, and we got to chatting. Three or four years ago, I said, “Look, I’d really like to do a retrospective screening.” I knew that they’d established, from the film archives, a re-mastered print of The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, so we set that up. It was extraordinary to see it play to a real afficionado film festival crowd of 20- and 30-year-olds in the Melbourne audience, who were just completely overwhelmed by the depth of its artistry. Around about that time, he said, “I think there’s a script of The Eye of the Storm floating around and it looks like finance is coming its way.” But, that was a long, difficult process, as it often is. So, he said, “I would really love you to play Sir Basil, and I think Judy Davis is very interested to play the sister, Dorothy.” At that stage, I don’t think he had Charlotte [Rampling] particularly in mind. So really, it was that combination of elements.

I’ve tried to interweave quite specific Australian projects, in and around things that have happened for me internationally, and this seemed like a good one to go out on a limb with, just to meet the challenge of Patrick White’s literary heights. If Ireland can claim James Joyce and South America can claim [Gabriel Garcia] Marquez, Patrick White is sort of in that league. Sometimes you think, “Well, this is such extraordinary novelistic writing, will it find its way comfortably into a screenplay?,” and you don’t know. But, if you’ve got people like Judy Davis and Fred Schepisi around you, that’s the best shot you can start with. You don’t want to short-change it and end up with a soap opera, but this resonates very, very strongly. And Patrick White, himself, loved movies. I got to know him, late in his life. I was involved with some of his later theatrical writing. He loved show folk and he loved theater people and he loved movies.

Since this film has taken a bit of a journey in finally opening in the States, has it been gratifying to get such great feedback on the film and your performances in it, and to finally have audiences get to see this work?

RUSH: Yes, very much so. To be honest, when it opened in Australia, Australians have a complex relationship with the legacy of Patrick White because people don’t read as much and, sadly, he’s a slightly forgotten figure. But, seeing it in Toronto at the film festival, and then [at the New York premiere], the North Americans aren’t too worried about the literary pedigree involved. This film is playing very strongly with areas of discomfort and concern that I have about my own family dynamics. Patrick had a very sardonic, very acerbic arch sense of humor, in a Tennessee Williams kind of way. It’s up there, in bold colors and heightened. So, it was very rewarding to hear how the American audiences came in on the humor. It’s the sort of humor where you go, “Oh, my god, I really shouldn’t have laughed out loud at that, but it’s so blunt and so honest that you have to laugh with it.”

You must feel a bit of pressure and a sense of responsibility in taking on the work of Patrick White, but at what point and how do you just put that aside and focus on doing the work?

RUSH: It probably follows the practical handbook of how films get made. There’s a loose pre-pre-pre-production period, where the idea is germinating and the excitement amongst a handful of people, of the potential that this might have, comes into play. Then, you get a phone call, one day, from them or your agent saying, “Oh, it looks like the script is in and they’re starting to talk shoot dates,” and then, it starts to become more of a reality. In that period, as an actor, I like to really hover over the production and stand outside it, so I can think about it in the third person, rather than be too self-absorbed in my first-person role, in terms of connection with the character. But then, when you get to the shooting, that’s when the team goes out into the studio or onto location to put down the jigsaw of the raw material that will be reassembled in post-production. So, I like to be ready and have done as much objective analysis and musings and discussions and living with the excitement of kicking around the ideas of the piece, so that when you actually get onto the floor where the money is really ticking over and you’ve only got a day to achieve a three or four page complex scene of dialogue and camera set-ups, that you’re ready to go into a strong mode of play.

Were there any particular challenges in understanding who Basil Hunter was, or did who he is come easily for you, as far as figuring him out?

RUSH: Well, I’m playing someone from my own country and from my own profession. That can be pretty confronting, particularly because he’s a major failure. When I started as an actor, I was 20 in 1971, and I knew a lot of actors in their 50's and 60's, at that point. It was a tradition that people abandoned the so-called cultural wasteland of Australia in the mid-20th century and went for the filmmaking in London. So, I had worked with a lot of actors, of that age group, that I had strong memories of. Plus, I had the great bonus of having a 105-page screenplay to be able to work in tandem with a 600-odd page novel of dense and nuanced prose. Part of Patrick’s style is that he was a genius with the interior monologue of what abstract stream-of-consciousness thoughts are happening inside character’s heads, as they go about their daily activities, and that becomes invaluable. It’s also 15% semi-autobiographical. I think, for Patrick, it was a metaphor that he made Basil an actor. He wanted a character who was able to go through such a sense of self-introspection, self-loathing and self-doubt, so an actor seemed like a good vessel to pour all those ideas into. I don’t think he was intending to satirize the acting profession, as such. It was also that sense of historical dislocation, of people who left their own country because they couldn’t realize themselves in that role and had to go to a different, slightly more superior culture. To then come back and face not only mother but the indifference of the continent all comes into play with it.

Sex scenes are obviously always somewhat awkward to shoot, but does it add an extra special layer of awkwardness when you’re doing them with the director’s daughter?

RUSH: I thought about this and I can only reference Pirates of the Caribbean as a way of describing it. When we did the first Pirates film, we had a couple of really great mentoring sessions from this wonderful sword master, called Bob Anderson, an Englishman who was probably in his early 80's at the time, and that was 10 years ago. He had mentored Errol Flynn and taught him fencing for films, back in the ‘50s. He played Darth Vader in the Star Wars films and did the very famous light saber fighting. He choreographed The Princess Bride. He was like the Yoda of the sword. When we were rehearsing the sword fights for the first Pirates film, he said, “Look, I know you guys have got no dialogue. What often goes wrong in sword fights is that people act out the look of people fighting with a sword, but there are purposes on every movement, whether it’s an aggressive movement or a defensive movement. Sword fighting is a complex, very sophisticated, nuanced dialogue between two blades, and that means, even though you’ve got no dialogue, you are moving in on someone. You’re defending and saying, ‘Take that! Ah, I tricked you there! I’m coming around here!’”

I think it’s the same with sex scenes, to a certain degree. There’s often rarely any dialogue in a sex scene. With your fellow actor, it’s good to talk about what the unspoken dialogue is, that’s happening in the scene. You’ve got to play something rather than feel self-conscious or exposed because, in your workplace, you happen to be naked in front of a lot of other people and you’ve just got to put that aside, in the same way that you have to put that aside in a fully-clothed intense dialogue scene because you’re entering into that particular imaginative state of play.

The most interesting thing about that day was that I learned a lot about Fred Schepisi. He said they’d spent a long time setting up the shot, and it was a very small, pretty average corporate hotel setting. He said, “I’m going to start very close on your face, Geoffrey, and then pull the camera back, as Basil is making love to Flora.” He referred to her as the character. He said, “When we pull back, we’re going to realize that Basil is actually looking at himself in a mirror, and the frame of the mirror will come into shot.” I thought, “That is fantastic! This is not just the solving of two people having sex. There’s a metaphoric overview of strange vanity and something discordant about the scene that’s also in there, in the structure of the shot.” It is a stunt sequence you’re creating. When you’re doing a fight, you don’t want to smack the other person in the jaw because then you’ll close down filming for a month, but you’ve got to make it look as though that’s really happening. Sex scenes are just a different kind of engagement.

What’s been the best part of your involvement with the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, and are you hoping to get to do another one soon?

RUSH: The best part, for me, has been that the writers have managed to give an evolution to the character. He started out as this spat out from hell villain who was the bad guy and an evil dude. And in the course of the subsequent films, he used those particular powers to become a politician, brokering a G20 summit of pirate lords. In the last film, he went over to the other side and worked for the king. So, on that level, it feels as though I’m going into a new terrain each time, which is terrific. And I believe, in the script that’s being developed for the fifth film, they do it with great care and consideration. The writers and Jerry Bruckheimer, as producer, can’t start a film like this, with a creative team that’s so huge and the amount of money that’s involved, without knowing that the script is in good shape. You can’t start shooting this sort of stuff, if there’s holes in it. But, as to when it will go, I know nothing.

After so many fantastic performances in your career, what do you look for in a project and role now?

RUSH: There’s no hard and fast criteria for that, I don’t think. The elements can be unusual. In the case of The Eye of the Storm, it was Fred Schepisi, the challenge of Patrick White’s novel, and knowing I could collaborate again with Judy Davis, who I’ve worked with on a number of films. They were the key ingredients to going, “We’re in for a ride on this one, and we’ll take all of our resilience and resources to try to match this material and bring it to life, in the best way that we can.” Something like The King’s Speech, that was the one that was lobbed onto my doorstep, and I read it and was attracted by the fact, primarily, that there was this fascinating, relatively non-stereotypical Australian character, in the center of a very particular international incident. That became the key spark.

Do you know what you’ll be doing next, or are you currently working on something now?

RUSH: I just finished shooting a film in Italy with (writer/director) Giuseppe Tornatore, who I think would be well known to North American audiences for Cinema Paradiso, which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. It’s a beautiful film, from 20 years ago. That film is called The Best Offer, and I believe it will be coming out later in the year or early in 2013. And then, I’m heading back to Melbourne to start rehearsals next week for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Have you ever had moments in your career where you’ve gotten bored of acting and thought about moving on to something else, or has it always been creatively fulfilling for you?

RUSH: Well, of course. One of the fine print clauses, somewhere down at the bottom of the job description, it says, “There will be many days in your life where you feel as though you’re hitting our head against the wall, and you will want to give up in complete despair, in a state of self-loathing, etc., etc.” And then, the print gets smaller and you don’t quite know what it says. Of course! But, I’m sure that can happen in almost any job. I think it’s about finding appropriate downtime. You’ve got to get away from it sometimes, and come back charged up again. Sometimes I’m back-to-back on projects, and that’s been exciting, to take the exhilaration of one job into the challenge of the next and feel as though you’re on fire, knowing you will collapse, three months down the road.

The Eye of the Storm is now playing in theaters in New York, Los Angeles and Florida, as well as on V.O.D. nationwide.