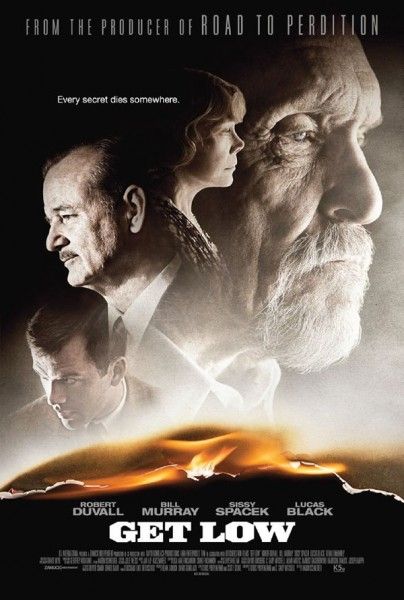

An 8-year labor of love for producer Dean Zanuck (Road to Perdition), Get Low is an entertaining and colorful story about one man’s last-ditch quest for redemption inspired by an eccentric 1930s Tennessee hermit known as Felix “Bush,” who famously came out of hiding to throw his own funeral party while he was still very much alive and kicking.

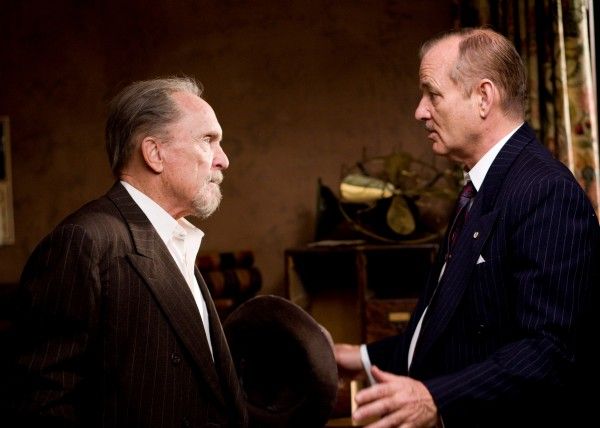

Based on a screenplay written by Chris Provenzano (Mad Men) and C. Gaby Mitchell (Blood Diamond), Get Low is directed by Aaron Schneider, a talented young filmmaker who makes his feature debut after winning the Academy Award for his short, Two Soldiers. The film features a terrific cast that includes Robert Duvall as the mysterious backwoods recluse, Bill Murray as the fast-talking funeral home owner who senses a big payday in the offing, Lucas Black as his young apprentice, and Sissy Spacek as a lonely widow and the only person in town who ever got close to Felix.

We sat down this week with Dean and Aaron to talk about their new film. They told us about the long evolution of their project, how a well written screenplay attracted such wonderful, iconic actors, and why a combination of good fortune, good timing and good instincts led to success. They also gave us an entertaining account of how they managed to wrangle one of the most elusive actor in Hollywood into their stellar cast.

Q: Dean, you have a huge legacy to live up to, how difficult is it for you to live up to the public’s perception of that legacy and does that have a strong bearing on the projects that you choose to become involved in?

DZ: I place the great expectations on myself more than I think the town places on me. I actually think the town has lowered expectations. I felt that early on in my career just working as kind of a “must hire” on my dad’s films, that many people had a preconception that I was just there to mill around and cozy up to the stars but wouldn’t be up for the grind or the hard work, and I immediately tried to set the record straight by just [showing that] no task was too menial or working overtime as a set PA or as an office PA. Everybody on the production is your boss and can order you around. As a kid, I didn’t think any other [way]. It was just a job. It was something I wanted to do well and I don’t ever concern myself with what other people feel about me. I know what my contributions are to any given film and as far as the selection of material, yes, I’m aware of the legacy and the stories are still shared across the dinner table. My dad [said], and my grandfather passed this on to my father, that you should always aim high with the story and let the story be your guide and nothing else, and I try not to let any of the other noise [distract from that], and it’s hard given how the business is today where story has been sort of knocked off the pedestal a bit in terms of its importance. I just go with my gut and don’t think about how much a movie is going to cost or how much I’m going to make or what the one-sheet in China is going to look like. If the script moves me or inspires me in such a way, I’ll roll up my sleeves and try to find a way to produce it and just surround myself with talented people and let them loose, and the results so far I think have been good but you’re only as good as your last movie, so we’ll see.

Q: Aaron, this is your first feature. What was it like working with such an incredible cast? Was it a little overwhelming to go on a set and direct these people?

AS: I’d had a chance to get to know Mr. Duvall over the many years in developing the screenplay. It’s funny, I met him in this hotel the very first time five years ago. I went to the restaurant downstairs and passed the table we sat at. I was just thinking about it.

DZ: He bought you sushi.

AS: He said, “Your Purim money is no good. I’ll take care of that.” And then the journey began in developing the script and our second writer, Charlie Mitchell, and I went up to his farm in Virginia a few times and talked about the screenplay, the character, and we all got to know each other and we all got to know this character together. So by the time the movie started I had a familiarity with him personally, but I was still, of course, in awe of his resume and his amazing skills. So yes, I always had a healthy respect for the people I was working with, but they’re also really cool people, you know. Bobby loved to talk about food and Sissy’s a sweetheart and Bill’s Bill. So, very quickly they put you at ease and you realize you are working with people who are there because [they want to be]. We didn’t have a lot of money to offer any of these people. So immediately you know that you’re working with people who care about the work. That’s a healthy atmosphere and there’s nothing intimidating about that.

Q: Can you talk about casting Bill Murray?

AS: He was always on our list. I think Dean put it the best way. He’s on everybody’s list but at the same time he wasn’t on ours in the sense that we had spent so long getting the film off the ground and fought so many battles that the idea of trying to wrangle the most elusive actor in Hollywood into our cast two months out of shooting would be just a little out of our depths. But credit Dean here who decided one day to call up his attorney and give it a whirl, and the attorney recommended that he send a synopsis and he would forward it to Bill but we’d most likely not hear back. He wasn’t being discouraging. He just had spent so many years with Bill as his attorney that he wanted to be realistic with the people that were looking for Bill. Dean called me one day and said “I’ve got a voicemail. You’ve got to hear this.” And there was Bill Murray saying “This is Bill. I’m interested in this role. If you still haven’t done anything with it, I’d love to read the script.” And he gave us a P.O. Box number and we jumped up and down. We sent the script off to this P.O. Box and then we went “Now what?” It’s not like we can pick up the phone and call the agent to see what he thought of it. It’s like we’ve got to wait to hear from him which was the most maddening thing. The one nice thing about agents and managers is that you can touch base, but not Bill. So a couple three or four weeks went by and Bill called Dean and he actually talked to Dean’s assistant, Lili, for a little while first. He was like “Is your boss a good guy?” “Yeah, he is.” “No, you’re lying, aren’t you? He’s….” She said, “No, he’s a good guy. He’s here too. You should talk to him.” So credit Lili for passing it off to Dean and then they talked and “Great! I’ll call your director. Give me his phone number.” And then, I went “Wow! Bill Murray’s gonna call me!” And then another day goes by and then a week and two weeks and I’m sleeping with the phone by my bed answering every call before I wake up. Normally, you let it ring up there while you’re asleep. Right? Well I put it by the bed. It’s the rug people and it’s the… I had no idea that many people called me before nine o’clock in the morning.

DZ: And then, when the call did come in, the phone was nowhere to be found.

AS: Exactly. (Laughs) Well that’s true. Isn’t that right? I had to run downstairs. Oh yeah, he called me. I have a 3-floor condo and I couldn’t find the handset, so I hit speakerphone and went “Hello” and he goes “Is this Aaron?” “Yeah.” “Hi. This is Bill Murray.” And I’m like “Whoa!” But the speakerphone wasn’t going to work for me because, I don’t know, maybe I was nervous and I like to walk and I didn’t want to have to shout across and I said “You know what, Bill, can you wait just one second? Don’t go anywhere.” And I went all the way down and I was pulling pillows up trying to find the handset. It was nervewracking. But we had a nice conversation and he said “Okay. This is interesting.” And he hung up and then he disappeared again and then I had to write him a letter. We were getting to that point where the investors included were so excited that if he was to fall out, if he was to say no, that maybe it would kill the buzz and we were getting to the point where we had to start talking about other actors. I didn’t want to let him go so I wrote a letter and sent it off to that post office box hoping that he would get it. We didn’t even know if he was in town, but he got it. So, credit Dean for not taking no for an answer and credit Bill for hanging in there with us.

Q: Can you elaborate on the term “Bill is Bill”?

AS: As far as Bill being Bill goes, Bill’s exactly what you’d expect. He’s funny all the time and he’s always looking to have fun. I think he works the way he lives his life. He tries to create as pleasant an atmosphere and be with as nice a people as he can find so that his life is what he wants it to be and that’s why I think he circles the airport with projects. It’s not so much…I think he’d probably already decided when he read the synopsis creatively that he was interested. He said as much, “This is an interesting project. I’d love to read more. Wow, this is a good script.” Yet he still didn’t say yes. I think what he was trying to do was get to know Dean and get to know me and he made the comment that he’d watched my short film behind-the-scenes commentary. In fact, at one festival, he said he has a tip for actors: watch the behind-the-scenes on these director’s DVDs and you’ll get a feeling for what it’s going to be like working on the set. Even though it was a short film, I’d thrown together a little home grassroots mini-DVD recorder type, not press kit, but little documentary on the making of my short and Bill seemed to like what he saw and felt like he was going to be with people he’d enjoy being with. So, Bill being Bill is just his joie de vivre.

Q: I understand that Bill Murray has an 800 number and that’s how people get a hold of him and I was wondering if you now have that number so you can get in touch with him more easily in the future?

DZ: I’ve never called the 800 number. I have other means of communication with Bill. But he does have one. I think the line producer might have it.

AS: Smoke signals. Right? (Laughs)

DZ: The line producer might have called it a couple of times. But sometimes Bill would pick up the phone and sometimes you’ll call him. It’s always sort of an adventure but once you have him, you really have him. He’s been to five film festivals with us including one in Poland and he’s really supportive and I think very proud of his performance, both comedic and dramatic, in Get Low. He’s very excited about it.

Q: There are different producers in town who have very strong brandings associated with their name such as Jerry Bruckheimer and Scott Rudin. Looking at the exquisite films that you’ve been involved in over the last decade, have you been trying to develop your own brand identity?

DZ: I’d never think that far in advance. Like I said earlier, I know it when I read it and I don’t think much more than that. There’s no type of story I want to tell. There’s no type of story I don’t want to tell. It wasn’t like I had an interest in a living funeral. It just hit me a certain way and if quality is a common denominator, then I’m not going to argue with that, but I think the studios appreciate those producers that do have that brand identity and maybe that will come. I don’t have the extensive resume as those producers that you mentioned, but I always aim high and so far, so good. On the set of Road to Perdition, they would always joke because I was a young kid producing that movie, and they’d always say “Where do you go from here?” You look around and you’ve got Tom Hanks and Paul Newman and Sam Mendes off of American Beauty. You know, you’re ruined. You can only go down. But then something like Get Low comes around and you have the opportunity to work with an exceptionally talented young filmmaker and a screenplay that attracts these wonderful iconic actors. It’s a combination of just good fortune and good timing and perhaps good instincts with story.

Q: Aaron, Robert Duvall talked about how he liked to butt heads with directors and liked having that tension. Can you talk about butting heads with Robert Duvall?

AS: Well I don’t know. Bobby is a formidable presence on a set. He’s all business. He knows what he’s doing and he’s been doing it for a long time. So he doesn’t suffer the…he wants everybody to be at the same level that he’s at so that’s what we strove to do. I don’t recall ever butting heads. It wouldn’t be in my interest to create tension. That doesn’t really sound like Bobby to me actually. I know he tells stories about directors he doesn’t like but I don’t remember ever having any conflicts. Sure, you have creative conversations and frustrating moments but he wasn’t scary at all to work with except to say that his legend is always there. It’s always present.

Q: How did you go about creating the look and tone of 1930s America in order to frame the story against an authentic landscape? Was it hard putting that together?

AS: Oh, what’s it like to put together that period? On a budget, it’s very hard.

DZ: That’s one car going around the block over and over. (Laughs)

AS: And we’re painting it different colors as it goes by because paint is cheaper than cars. (Laughs) My short film, my Faulkner short that Dean mentioned, was period and set in the South in the 40s and I had a little experience with how you could… If you stay open, if you go to these little places that you need a barn, you need a house, you need a church, if you just keep your eyes open and you look for places that are untouched by time, that you know you can subtract modern things from and then throw in a few old things. You can’t afford to build anything so you’re looking for these places. And, in fact, everybody thought I was crazy but before we started shooting I went on Flicker.com. The craziest thing is there are billions of pictures on there and things like old houses, old churches and barns, and mountains and everything we needed. All you have to do is type “old house Atlanta” or “old barn” or “old church” and you get all these old places because these are very cinematic things for still photographers to shoot. They attract photographers. So they were all over Flicker. And if you put in “Atlanta” in the search engine, you could actually start to take a tour of these things. You could actually start to tour Atlanta through these pictures. And many times the people who posted these pictures would say “Oh there’s this old church out by I-29,” so we were able to fish out some of these spots with Flicker.com even before we landed in Atlanta.

Q: In this film, you establish an unhurried rhythm and at the same time build a dramatic momentum and simultaneously have a whimsical feeling and at the same time create something that has enough gravitas that it really pays off dramatically at the end. Can you talk about managing and maintaining the tone of the piece?

AS: It wasn’t until I started putting it together that I realized how complex all those things you just mentioned were. I was going by my gut instinct. I was looking for truthful performances in truthful locations and when we developed the script we were looking for a beautiful, old fabled folktale kind of whimsy, yes. And that’s all in the writing. But you’re right. Then it gets down to, you can call it that, but then it gets down to the nuts and bolts. It’s like well how do you translate that? It’s just instinctual, I guess. And when all else fails, it’s just what feels truthful, what feels right. You’d have a conversation with the creative team about making the movie feel like an old book. You can pull a book off the shelf. How does it feel, how does it smell? It’s a little yellow, not a lot of color, but it’s easy to read. The print is still beautiful and bold. It may be old but it’s not hard to [read]. It’s not inaccessible. So you talk about things like that just to get your creative minds in sync with each other and then you set about trying to find ways of expressing that in every little moment or in any decision or whether it’s an actor or a piece of furniture or the photography. So I credit the writing and all these wonderful artists – these actors and crew that helped me translate it.

Q: Would you say you found it more on set than editorially?

AS: You find it everywhere. It’s something you’re responsible for all the way through in the development of the screenplay and in the kind of movie you want to make through the wardrobe choices and then the performances and balancing the gravitas of Duvall’s character with the eccentricity of Bill’s performance. A good example there would be that Bill knew that the tone of his performance was going to bounce off Duvall in a big way and create an overtone, you know, a third feeling. Here’s me, here’s him, and then they collide and how does that feel? So, I think Bill, very smartly and wisely in multiple takes, played around with different ideas just to see for himself and feel for himself what was working, what felt like it resonated in the room and the scene and what didn’t. And then you get into editorial and you put them up there and go okay, now you have a rainbow of different choices to help radiate that kind of stuff. So, to answer your question, that takes place throughout the process all the way.

Q: Aaron, being that this is your first feature film, what’s it been like working with these incredibly talented people and hearing this early Oscar buzz?

AS: I’ve been through that with my short film which won an Oscar in 2004 and it’s pretty hard to describe any of those steps whether it’s talk, buzz, nominations, wins. It’s a wonderful feeling but I don’t think so much for the award itself, although you’d be lying if you didn’t say the Academy Awards are exciting. It’s really about when people whose work you respect respond to yours, that’s the best feeling you can have. Last night at the premiere I had a couple heroes of mine. I had Owen Roizman there who photographed a couple little movies called The Exorcist, Tootsie, The French Connection -- nobody recognized him on the red carpet but [he was] one of the greatest filmmakers in the room last night -- and Caleb Deschanel who shot a couple of little movies like The Black Stallion and The Natural, and these guys came up afterwards and congratulated me and told me what they liked and that’s just so [rewarding]. So, if people think it’s worthy of that kind of conversation and the people themselves are people I admire and peers, then that’s wonderful. The awards, that’s for the fates. But the feeling that they’re responding to your work, that’s a great feeling.

Q: Aaron, you’ve got incredible actors like Bob Duvall and Sissy Spacek who say they didn’t really rehearse that much. They have these two major scenes with each other. Can you talk about how you worked with them and how many takes there were? Did you just let them do their thing?

AS: Yeah. As far as how to direct Sissy and Robert Duvall, there’s this concept that directors say “Do this, do that. This is your motivation. Stand here. Be sad. Be happy.” I think the best way, when I was working as a cinematographer and learning from the directors I worked with, what I learned from the best is that their job one is to create an atmosphere in which these actors can do their best work. It’s about creating a comfortable set. It’s about putting reality and authenticity and truth around them in the room so that they feel like they’re in good company. And then, of course, I would be a fool to assume that I could help Robert Duvall in his process. That’s ridiculous. My responsibility is to put the performances in the context of the story. Robert Duvall is the author of his character. I’m the author of the story and the character is an element in that story. So the input I had, had more to do with making sure his brilliant ideas fit inside what I wanted to do with the bigger picture. But my job was pretty darn easy too because of what they bring with their craft. It was just amazing.

DZ: It should be noted though, because you mentioned takes, the speech at the end was a single take for Bobby and Sissy’s reaction to Bobby’s speech was a single take as well.

AS: We knew that was the big money day. The funeral party was shot over 3 days and we started big with lots of people and extras and we shrunk in the second day and then on the third day we all knew we were going to get into the close-up coverage of the speech and Sissy’s reaction to the speech. That morning, I remember sitting in the make-up trailer in between Mr. Duvall and Sissy and we were just talking about it. We were just grinding out ideas and everybody knew that this was it because this movie is not a plot climax. It’s an emotional climax. You can set gasoline explosions to a certain level by measuring, but how do you create an emotional climax? You can’t. You have to just nurture it. You just have to trust in the words of the screenplay and the actors. So, we talked about it, set up 3 cameras, brought Bobby out, rolled the cameras, and what you saw is what he gave us on the first take. It blew us all away. Bobby and I had a quick word and we both knew immediately that that was it. I turned the camera around, brought Sissy in, and Bobby delivered his speech for her one more time at full force to help her and she gave us this marvelous [performance]. If you think about all the things that she’s putting together emotionally, all these windows being blown open for her, 40 years of her life are being redefined and she’s reliving the pain of losing her sister, while the story of how is completely changing on top of it, and every single beat of that was in her face and I’m like “Cut! That’s going to work out pretty well. Let me go home and slice these two things together and make a movie out of it.” So yeah, they were single takes. It was the coolest moment of the shoot watching these two masters throw down.

Q: Can you talk about your upcoming projects?

DZ: As far as upcoming projects, as a producer you always have to have a couple in the hopper. You never know which one might take flight. Hopefully, the next one won’t take 8 years. I have an Italian novel that I had translated called “Voice from the Stone” which is essentially a ghost story sort of like the others – Rebecca – a bit of an atmospheric thriller concerning two women who are fighting over the love of a single boy and one is the nurse who has come to the villa to help treat the boy who can’t get over the traumatic loss of his mother and the other woman is the dead mother. So it’s kind of spooky, it’s kind of creepy. There’s a few other projects but that one I think is next up, and (turns to Aaron) let’s hear it Aaron. C’mon, tell the world. What have you got?

AS: (Laughs) Well, for me, it’s always been kind of taboo to talk about what’s next, but I’ve got a few projects that are interesting and I’ve been doing a lot of reading. For the most part, I’ve been with this film. It’s been my priority – getting it out into the world and we’ve been on a long festival tour for the 8 months in between when Sony Pictures Classics bought it and now. Last night was a real rite of passage. It was a threshold. It wasn’t just our premiere. It was the end of a period where I got to see the world and go to different festivals and share the film with audiences. I sat in every one of them to try to feel the audience and learn from different cultures, different audiences. So I’m still spinning a little bit.

Get Low opens in theaters in New York and Los Angeles on July 30th.