In 1968, author and social critic James Baldwin went on The Dick Cavett Show and had to explain to a Yale professor how racism functions and that just because there are similarities between individuals, we have to look at how institutions function. Fifty years later, we have Green Book, the reigning Best Picture Oscar winner that thinks that the Yale professor was on to something despite all the evidence to the contrary.

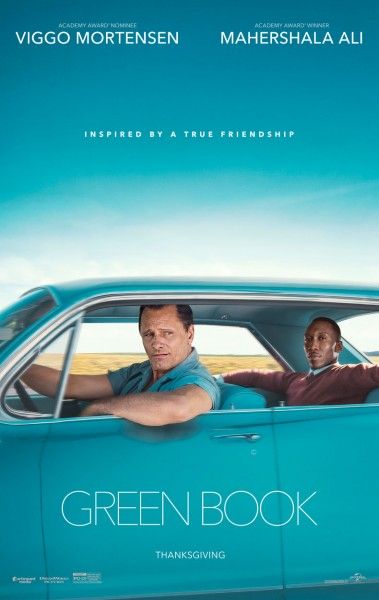

For those unfamiliar with Green Book, the film, directed by Peter Farrelly (previously known for comedies such as Dumb and Dumber and Stuck on You which he co-directed with his brother Bobby Farrelly) is based on the true story from the 1960s between Tony Lip (Viggo Mortensen) and Dr. Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali). Lip is an Italian caricature, a tough guy working at the Copacabana who needs work when the club shuts down for renovations. He eventually lands a job working as a driver and bodyguard for Shirley, an esteemed black intellectual and classical pianist who wants to do a tour with his band, the Don Shirley Trio, around the American South. Although Lip starts out as so racist that he throws away drinking glasses used by African-American workmen who come to his house, he eventually admires Shirley and the two appreciate each other as individuals.

For Green Book, this is the solution to our social ills: racism might be institutionalized, as we see throughout the South in the places where they’ll let Shirley play piano but not use their restrooms or eat in their restaurants, but if we can just be nice to each other and see other people as people, then we’ll be okay. It’s telling that the protagonist of this story isn’t the accomplished and fascinating Shirley, but Lip, the racist white guy who is absolved of his racism because he was nice to a black guy.

Green Book isn’t a “bad” movie. It’s got really good performances from Mortensen and Ali, it tempers a lot of its observations with a healthy dose of humor, and it wants to show how stereotyping is bad. When Lip is shocked that Shirley doesn’t eat fried chicken, it’s a racist observation cut with the humor of an ignorant white guy being comically ignorant. We, the enlightened audience, know that it’s racist to assume all black people liked fried chicken, but Green Book lets everyone off the hook because Lip doesn’t mean offense, Shirley warms up to eating fried chicken, and we can all agree that fried chicken is delicious.

This brings us back to the point of the Yale professor that got shut down by Baldwin back in 1968: Our anecdotal, individual ties are what matters. But it only matters to white people who don’t ever have to worry about institutionalized racism. The purpose of a movie like Green Book is to appear socially conscious, but never to offend and never to question. Even though it’s working from the obvious standpoint of “racism is wrong”, the movie suggests the tonic to that racism is that white people and black people should just start seeing each other as people. If we take things on a case-by-case basis, then there’s hope for us all.

Hope is a fine thing, but removed from context and labor, it’s largely indistinguishable from a wish. And wishing that racism will go away as long as people are nice to each other is a childish view, and one that seems incredibly irresponsible. It’s a viewpoint meant to soothe white audiences rather than encourage empathy and understanding. It’s the message that says, “As long as you’re personally nice to black people you know, you don’t have to confront the larger systemic racism affecting our society.” Green Book is the “Some of my best friends are black” of movies.

When you try to soothe your audience in this way, it lulls them into a sense of complacency. You don’t walk out of Green Book with a sense of urgency or any introspection. You’re supposed to walk out of it smiling because Tony Lip and Don Shirley became buddies despite their differences. And if you’re not willing to challenge your audience on the issue of race, especially in 2019, then what’s the point? Why bother making In the Heat of the Night over fifty years since that movie came out? What is the point of Green Book other than to make white audiences feel a little better about race in America?

What’s particularly infuriating is that we’ve seen that you don’t need to preach at people or shout them down to make a compelling movie. Get Out is a rollicking horror-thriller with excellent jokes, but it’s a movie that’s about white complacency and how black people can exist, but only for the purposes of white comfort. Just last year we also got The Hate U Give, a coming-of-age movie that also tackles the importance of listening to black voices and the problems with code switching. I’ve heard Green Book compared to Hidden Figures, but Green Book is told from a white man’s point of view, while Hidden Figures is told from the points of view of three black women. The white people in Hidden Figures are largely relegated to supporting roles while highlighting the excellence of three black women with the subtext of how much further we could have come as a nation if we weren’t hamstrung by systemic racism.

There are also tough movies that approach this subject. Documentaries like I Am Not Your Negro, which is about Baldwin and his views on race in America, and 13th, which is about mass incarceration of African-Americans. These are not easy movies, but not all movies should be easy. Sometimes things are difficult because they’re important. Even a film like BlacKkKlansman recognizes that for all the jokes made at the expense of buffoonish klansmen, it still needs to end on a down note because paranoia and fear permeate black life in America. Green Book wants you to feel good about progress in America without doing any of the work and ignoring the systemic racism that’s bigger than its two main characters.

And yes, a movie about systemic racism is a much harder sell. It likely won’t offer any easy answers. There’s probably not a scene where two characters recognize their own personal prejudices and later have an important handshake to show that they now respect each other. But if we’re just offering movies like Green Book where racism is a thing of the past, a thing that comes from individual belief rather than social factors like redlining, mass incarceration, and more, then injustice finds a place to hide. It hides in warm, fuzzy feelings that haven’t been earned and lessons that haven’t been learned. I’d rather a movie made me feel bad for a good cause than feel good for a bad cause.