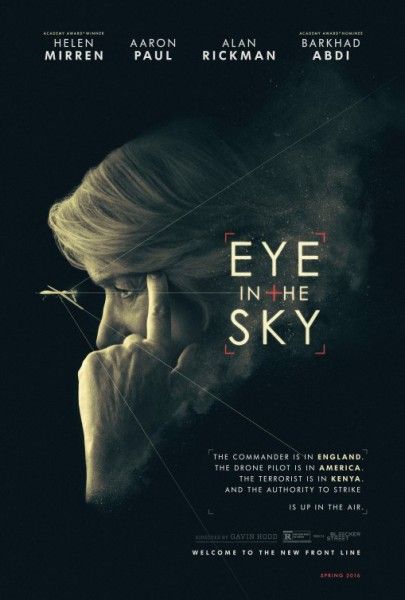

Gavin Hood’s suspenseful new thriller, Eye in the Sky, explores in real time the moral, political and personal ramifications of modern warfare and how hard decisions must be made even when disparate international agendas are at stake. The film stars Helen Mirren as a British military officer in charge of a high level drone operation targeting terrorists in Kenya. Relying on remote surveillance and on-the-ground intel, her mission escalates from “capture” to “kill” when she discovers a suicide bombing is planned, but her ability to strike is complicated by the fate of an innocent child. Alan Rickman and Aaron Paul also star.

At the film’s recent press day, Hood and Mirren revealed what drew them to the project, how the role originally written for a man was changed to a woman and Mirren was approached to play the part, the challenge of portraying events from multiple perspectives while shooting on a limited budget, how Hood sustained the energy of scenes set in confined spaces and kept the action powerful and intense, the extensive research by Hood and screenwriter Guy Hibbert and using military consultants to ensure the film’s authenticity, their memories of working with the late Rickman, and Helen’s upcoming drama, Collateral Beauty, with Will Smith. Check it all out in the interview below:

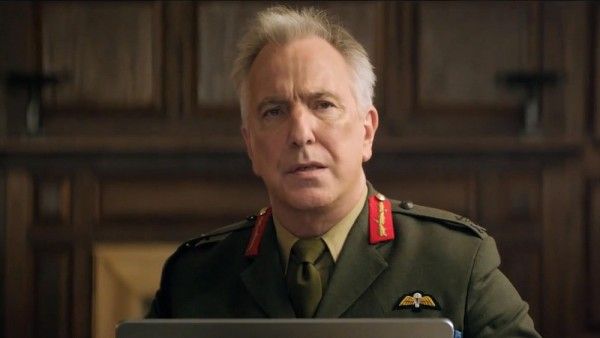

This past month we lost a great actor, your co-star Alan Rickman. Would you both kindly say a few words remembering what it was like working with Mr. Rickman?

HELEN MIRREN: Unfortunately, in this film, I didn’t actually get to work with Alan, because we all shot our pieces separately. But I have worked with Alan in the past, on stage actually more than in movies. I think that Alan would have been incredibly proud that this was his last movie. It is what I love about it, which is that the Alan you see up on screen is much closer to the real Alan Rickman that we all knew and loved. You see his intelligence, you see his wit, and you see his authority. I think that that was very much the Alan that we knew. The other characters that he played so brilliantly in the Harry Potter series, and as the baddie in Die Hard, and those sorts of things, he was a wonderful actor, so he always gave an incredible performance, but I think the Alan that we see on screen in this movie is very close to the real Alan. I also feel that the inner soul of the film is very much something that Alan would have identified with and would have been very proud to be a part of.

GAVIN HOOD: Helen put it beautifully in terms of describing Alan’s personality and what he brings to it – his intelligence, his wit, his warmth, his love of people. I sometimes feel a little awkward answering this question, because unlike Helen, I only met Alan on this film. So, I haven’t known Alan his whole life, and I feel very privileged in a way to have worked with him and also slightly awkward, because I can’t believe he’s not here to articulate for the film and what he feels about the ideas raised in the film, which Helen was alluding to. He did have strong feelings about the concepts and the themes and the ideas raised by the film, and I wish he was here to articulate them because he was so articulate. As a director, you’re working with actors like Alan and Helen and the actors in this cast, who are highly intelligent people who genuinely think about what it is that we’re trying to do. I can’t really say anything more other than I’m so sorry that he’s not here to sit with us and lend another voice to this interesting conversation that the film throws up based on Guy Hibbert’s wonderful script. I just feel very fortunate to have been able to work with Alan. I had no idea it would be his last film, and it feels strange to me that that is the case. I’m very proud to have worked with him and to have him in this film.

For both of you, how did this project first come together?

MIRREN: I think you should start. It starts with you.

HOOD: Yes, I read the script, and now I can explain how I became so thrilled to have Helen in the film, because I was, as directors do, reading scripts and looking for something that would really capture me. One reads many scripts, and some of them are good and some of them are not, but every now and then, one really grabs you. You simply can’t put it down. That sounds like a cliché, but if you’ve seen the film, I hope that it keeps you on the edge of your seat. Well, the script did that for me. I was on the edge of my seat. I turned the pages. I wanted to know what was going to happen next. So, there was the thriller element, the entertainment factor, if you like, that said, “This is really exciting.” But then, there was another layer, which was, “Wait a minute. I thought I thought this, and I’ve just turned the page, and the character has said something that has just spun my head in another direction, and what do I think now? So now, I not only want to know what happens next, but what do I think should happen next? And if it does, how will I feel?” As I was reading the script, I thought I really want to make this for those reasons. Helen and I, this is our first time sitting in a conference together, so this is kind of fun to be able to tell her this. For some reason, I kept thinking, “Helen Mirren, Helen Mirren.” You may not know this, but the character was not written for a woman. It was written as a man. Colonel Powell was a man. I kept thinking I’ve got to have an actor who’s steely, determined, intelligent, has a real presence and the ability to look…

MIRREN: Sexy.

HOOD: That too. Very, very sexy. And especially because the wardrobe is so appealing. I mean, I really need someone who can pull off the wardrobe. I love it. See, she’s totally thrown me. So, who will play this character? For some reason, I kept thinking of Helen as an actor, male or female. But I also confess that I thought to myself when I got to the end that this is a subject that should be talked about by as many people as possible and that women should not be excluded from this conversation by having a male-dominated cast that makes it look like a Boy’s Own war movie, because it’s so much more than that. So, not only was I fortunate enough to get the best actor for the role, but I also got a great actress, if I may, who I hope appeals to men and women, especially because she’s sexy. Let’s be honest, Helen brings an incredible strength and power to this role and the ability to play those still moments. I love those moments where we push in on you, and you’ve just realized it’s been done, and the ambivalence that you feel. You knew you had to do it. I mean, you can pick out so many of those moments. So, I fell in love with the script, and I thought of Helen, and I called the writer, and I said, “Guy, I love it, but I have one question.” In fairness to Guy, he hesitated only for a few moments, because as a writer, he’d been doing this, and now this director is going to change it. He said, “I know Helen. Why didn’t I think of that. Yes! Okay! Do that! Do you think she’ll do it?” I said, “I have no idea.” So, now I pass to Helen who then received the script through her agent, I believe.

MIRREN: Then I received the script. I didn’t know that there was this backstory of this originally being written for a man. I so applaud you, Gavin, not only for casting me -- obviously that was great for me -- but any woman. I love how you articulated it just now that it takes it out of just being a Boy’s movie about war, and I think it makes it much more universal that we are all a part of this conversation. I really applaud you for that. I wish more directors and writers had that point of view. I received the script, and like Gavin, I had exactly the same response to it. It was an absolute page-turner, but I thought much more than that. The subject matter was serious and threw up a conversation that I think we all need to be having. This is the reality of war in our present day and age, and I can only assume will become more and more prevalent as we travel through time. So, we need to discuss this and really be aware of what the various issues are.

I thought this film was a great war film. So many war films are basically good guys and bad guys, but this is not. Of course, we do have bad guys in it. It’s about the terrible moral decisions that any war throws up. So, I thought it was wonderful, and I hope that it will go into the canon of great war movies. There were a couple of other projects that were flying around at the time and were a possible conflict with this, but I said to my agent, “That’s the movie I want to do. If there are any conflicts, I’m telling you, that’s the movie I want to do.” At that time, we didn’t have distribution. Gavin went into this film with enormous courage without distribution, along with his financiers and distributors. It was really what they call a small film, one of those small films that are very, very delicate little flowers, because if you don’t get distribution, it’s straight to TV basically. I really thought it was one of the most exciting scripts I’d read in a long time.

HOOD: Me too. And it’s a credit to Guy. He’s a great writer.

MIRREN: Yes. And who I had worked with before. He’d written one of my Prime Suspect series and a wonderful one that was really very, very powerful. So, I had worked with him before as a writer.

Can you talk a little bit about any research that you did ahead of the film?

MIRREN: We were very lucky. We had a British military man who was on set all the time. Also, he was very accessible for me. I had long conversations with him about who Colonel Powell might be. Obviously, she’s a woman who’s joined the military maybe in her early twenties, maybe even her late teens, at a time when that was not commonplace. So, what kind of a girl decides to do that in the first place, and then has the abilities that have brought her to this position of authority and power within the military? He was great in helping me, giving me guiding points about what he felt that sort of woman would be. And then, he was very, very valuable in terms of literally physical things, about the way you wear your uniform and the way in which the behavior is.

HOOD: Obviously, when I’d read Guy’s script, I was somewhat intimidated, because there’s a tremendous amount of research that he’d already done and I needed to catch up. So, I immediately dived in. I started on the internet and then I called some friends that I have in the military. I know a Colonel who’s in the Air Force who knows Colonels who know other Colonels. Before you know it, it was amazing to me how the Air Force was willing and happy to talk to me. I want to say thank you for those folks in the military who talked about it, because for them, they are the guys, these Colonels who have to take care of these younger pilots. Then, we got an American drone pilot who came on as a Major in the Air Force and still flies drones, and he’s consulted with us, and he still consults for us. Their dilemmas are not unlike ours. There are some people who say, “Military people are tough. They wouldn’t cry over this.” The answer is that is not fair and not true, and I’ll tell you why.

Having been in the military myself, there is an awful moment when you’re in this moment of conflict. For Aaron Paul’s character, that is the first time he is asked to do two things: one, fire a weapon in combat, albeit that he is far away, and two, in addition to that which will be bad enough, taking a life is bad enough when it’s the enemy, he’s also asked in this process to take an innocent life. It is easy for some people, I’ve heard them say, to be glib about this. “Oh, military people are tough.” Yes and no. It’s why these pilots experience double the amount of post traumatic stress that a fighter pilot does. I got this from our consultant who was an F-16 pilot who had flown in the Iraq war and dropped payloads over Iraq. He said, “I get to fly out. I drop and I leave.” And he also said, “Now, I drop and I stay, and I go back and look, and I have to identify the bodies. Some days it’s a bit much, because then I go home right then. Whereas, when we were flying in Iraq, I was at a base. I went and had a beer with my buddies. I didn’t have to go home to my wife.” Again, it was a conversation that actually the military were happy to have, because the Congress has been pushing for the expansion of this drone program, and some people in the Air Force are saying, “Slow down. We’re burning out these pilots. It’s hard to keep recruiting them. The Sensor Operators are as young as 19. They don’t necessarily cope.” Phoebe Fox (who plays Sensor Operator Carrie Gerson), by the way, I think we should say does a wonderful job with that.

All of these characters, I want you to know, are accurately researched. We didn’t make it up. I spoke to many people in the military. I also spoke to people who infiltrate in London, including an amazing undercover person who infiltrates the mosques where people are being recruited to go, so that those kids arriving on planes are accurately researched. Susan Helen Danford was the character we based on a real British woman, Samantha Lewthwaite, who used to be married to a 711 bomber who’s now in Somalia. So, I do think, with Guy’s research and then with me playing catch-up, you can believe that there’s accurate research in the film.

You spoke about the still moments in this movie which are incredibly powerful and intense. I’m wondering, for both of you, were there new tools in your toolbox that you were able to access in playing these still moments out?

MIRREN: We were very lucky in that the film happens in a sense in real time over the two-hour period. That’s the idea, isn’t it, Gavin? The two hours that you watch it in is the two hours in which the film happens. You had done all the ground stuff before I came onboard.

HOOD: No, no. You were my first up. She doesn’t know.

MIRREN: Oh, I was first up. The politicians hadn’t been shot. The drone pilots hadn’t been shot. We all shot completely separately from each other for financial reasons. They couldn’t afford to bring us all to South Africa. We shot it in Cape Town. We couldn’t all stay in hotels while everyone did their part. To save money, the people in the bunker with me were all brought in, and we just shot our stuff. When I was talking on the phone to Alan or to Aaron, I was actually talking to Gavin or the 1st AD or the sound guy. So, there we are in our bunker. I’ve never shot a movie like this. This director had to keep in his mind all his cuts, the rhythm of how people would be talking in this room, how it was going to interact with this. It was extraordinarily complex actually. We spent half a day, Gavin and I, just thinking about how we were going to shoot it, in what sequence, how we were going to do it. Basically, very roughly, we shot the whole movie, as far as my character was concerned, in one direction, from beginning to end. Then, we turned around and shot the whole movie, from beginning to end, in another direction. Again, financially, it was the most economical way of doing it. I’m actually ultimately speaking to your point, that I was very lucky in a sense that I could keep the sequence. Every day I was dealing with the sequence of what had happened and exactly where each moment sat within the whole piece.

HOOD: What Helen says is exactly right. We really did have financial constraints and some time constraints, and it was quite intimidating just to figure out how will we do this. It was also about availability. Helen was available for a certain window. Alan Rickman was available for a different window. Aaron Paul was available for a different window. How am I going to do this? Obviously, in a perfect world, everybody’s there. When they’re not on screen, they’re reading the lines off camera. If you had the money and the time, you’d keep everybody for the full six weeks and off you’d go. That wasn’t the case. Helen was first up, which means that all those screens that you see in her bunker are just green. In fact, they were just a big white sheet actually, because we were using some of the light through there to bounce off her. Anyway, the action that happens on those screens and the way the screen is divided into thirds with what’s happening in the house in the center, what’s happening inside the house, and so on. So, I did have that in my mind how it would ultimately be structured, but we hadn’t shot the material. What Helen had was a bunch of little crosses in the middle, and “This is where the house is. When your eye line’s there, that’s the house.” “Which house?” “The house from the top, Helen.” “So, we’re not inside?” “No, no, the one from the top. Then, this one is inside, and over here is where the characters will pop up if they’re talking to you.” We marked all these spots, except now we have those moments. But then, what are the moments? It’s a credit to Helen and Aaron Paul and Alan Rickman and Jeremy Northam and all the actors in this movie and their power of imagination, which Helen has said before is the ability to react and listen, but also the ability to imagine the scenario that in many cases does not exist, and in this film, more than any other, did not exist. There’s a blank screen and all Dame Helen Mirren has is my voice hiding behind going, “Alright, Helen. The child is walking out from behind…”

MIRREN: But you were great, Gavin. You were fantastic.

HOOD: And I’m thinking, “Am I doing this too loudly? Too softly?” That’s all I could do.

MIRREN: He talked us emotionally through it, and it was absolutely invaluable.

HOOD: So, that was how we did it. Then, Aaron Paul arrived and Helen had to go. Aaron was in a similar situation in a tight space. To answer your technical questions, one of the things that’s so important in this film for me is those tiny moments. The way I felt I would approach those moments was by keeping my actors’ eye lines very tight to the lens. I remember there was one moment, I’m not sure if it was the first day or two, where Helen was saying, “Does this director know what he’s doing?” You may not remember this, but I remember being terrified, because I thought, “I need to tighten her eye line, and I need her to be on that mark as the camera lands here, because I want to look right into her eyes, and I’ve got a certain key light here. If I’m off that mark by a half a foot, the impact is slightly profile.” I remember thinking I have to say to Helen I really need this moment, and she went, “Alright then.” It was those moments for a young director working with a seasoned professional, and I’ve not worked with Helen Mirren before, and I was thrilled. Then, after that, we got on great, because I knew that she understood what I was trying to do. I think maybe you felt in a moment that I wasn’t a complete idiot. It was great, and that’s how it worked with all the actors.

With Aaron Paul, we went even further inside that drone. How do you give energy to what is essentially a great deal of static people? My fear was, as Helen said, it might be a TV movie if it doesn’t have enough energy. With Helen, we placed her desk right at the back of a large, long room this size. That was a designed set. The idea was to allow my actors, especially Helen, to move towards the screen, and you’ll see how much she does that. She saw the space. I didn’t have to say anything. “Oh, I know, I’m going to move forward and intimidate that lawyer now. And then, I’m going to walk away from him.” But that is also something you do in production design. If the space is not the right size, the actor has no space to move. So that’s just staging. Aaron, of course, couldn’t do that, because he’s confined to a room. He had to know where to go. Then it’s about where can I put the camera to get that kind of energy. The camera was either very profile over the two of them to create that bond between him and the young Sensor Operator, or it was right in their face. I chose to play the eye lines into camera. It was a bit of a risky moment, but I think it pays off. It’s so in your face that you feel his pressure looking at that screen.

So, those are slightly unconventional ways of saying I am going to get inside the minds of the characters by going to the place where actors are best, which is in the eyes where the subtlest of moments happen. We read each other’s emotions without realizing it through slight, subtle changes in the iris and little things. If the actor is feeling it and using their imagination, when those subtle things are happening, as a director, you want to be there to get it. And that’s about having tight eye lines.

In doing this film, what were some of the things you found out about drones and the sort of fighting that’s going on? What surprised you about it or affected you?

MIRREN: I had no idea how far the technology has gone, and because it’s gone this far, how far therefore will it go in the future, in the next ten or twenty years. That completely took me by surprise. You read in the newspaper there was a drone attack somewhere. I’ve never really thought about it, and it made me obviously really consider the reality of this stuff on the ground and the extraordinary way in which warfare has changed. You think of the 19th century idea of warfare with people riding into battle on horses with sabers, and then the First World War idea of trenches and guns, the Second World War idea of airplanes and bombs. And now, we’re sort of in this Third World War and warfare is continuing on, and I suspect it will be very much a part of the future. I do remember my parents, who went through the Blitz in London, said the most terrifying thing about being bombed was not actually the German airplanes coming over, although that was terrifying. It was what the Germans had invented, this thing called the Doodlebug, which was a very early form of drone warfare, which was an unmanned vehicle that came over and made this drone sound. She said the terror was when you heard the sound stop, because when it stopped was when it dropped its bombs. So, my mother, in a way, had a firsthand experience of what these people must experience. It must be so terrifying, because it’s coming out of nowhere. You don’t know that it’s coming.

HOOD: Picking up on what you said, Helen, one of things about research in terms of areas where there is constant drone surveillance, especially in the tribal areas of Pakistan, where there’s drone attacks on a fairly regular basis, is that that population is very traumatized by the sound of drones and also by the weather. Now this sounds crazy, but obviously the one thing that these drones can’t control is the weather, and they don’t do a very good job when it’s an overcast day. So, the kids in these areas go out to play in the streets when it’s overcast. But a sunny day is a scary day. That, to me, when I was reading this, was just horrible. Whatever our feeling of whether we need to be doing it or not, it’s just that fact. Now expand that, because the concept in the military is the idea of moving to a state of total situational awareness. That’s the quest. If you’re in the military, such as the character that Helen plays, you can completely understand why you would not want to be the person who missed catching the kind of thing we see in the movie. Well, in order to achieve that, there’s an impetus to have more and more surveillance, more and more armed surveillance hovering over as many places as possible.

So, think of the way we now collect all of our telephone calls. Well, the next step is to collect all of us visually, all the time, everywhere. Now we have that in London, and in many ways, it makes London a very safe city in the sense that there are cameras on the streets, but they’re not yet armed. The idea of the drone world is that if we really want to know what’s happening, like in the incident that happened here in California. If we had the drones up all the time, watching us all the time, ready to launch their weapon at any time, at any target, let’s not talk about whether that’s a necessary thing or not, it’s just creepy in and of itself. That’s what fascinates me and I don’t have a good answer for it. The technology, as Helen was saying, is evolving all the time, and not only the technology, but the amount of the technology that we can use. When drones started, there were a few. When we shot the movie, there were 65 permanent orbits. Now, I don’t know how many there are. It’s moving in that direction.

So, that’s the kind of policy question. To what extent do we want to feel permanently under surveillance in order to feel safe? To what extent does that start to make us feel we’re potentially living in a police state? I don’t know. That’s why I love this movie, because it presents us all with enough information visually to begin to have a conversation. Before I did this movie, like Helen, I knew about drones, but I didn’t really know the details of them. What I think we hope from this film is that you’ll have a tremendous thriller experience, and you’ll be on the edge of your seat, but at the end, hopefully, these are the kind of conversations that it will generate over your dining room table.

MIRREN: When I was watching it, I was thinking in a way it’s like a courtroom drama and the audience are the jury. And when the jury leave the theater at the end of the film, now they’re going off to make their decisions about what is right and what is wrong. I’m really hoping that people will leave the theater, go out to dinner and have very intense conversations about morality, philosophy, and the human factor.

HOOD: At the end of the day, one of the reasons I think this script of Guy’s is so powerful is because he does show the problem or the situation from multiple points of view, including the point of view of the innocent bystander who is affected by the decision to strike. Once you do that, you’ve humanized that innocent person as opposed to seeing them as some sort of number. Not only do you humanize them, and therefore encourage anyone involved in this dreadful decision to pause before simply taking a life, but also you realize that if that life is taken, anyone who associated with that life may not feel particularly kindly towards the people who launched that missile. That is where the Monica Dolan character comes in who we were talking about who does such a fantastic job.

MIRREN: Yes. She’s very good. She’s the female politician who argues the case of not doing it.

HOOD: What I love about that character, and especially Monica’s performance of it, is it has for me one of the most powerful lines in the film, where you think that she doesn’t want to do this because she’s touchy feely about the little girl. You know, it’s imposing the classic male view of the woman as the touchy feely. And then, she says, “I wouldn’t do it, but not necessarily for the reasons you think.” She says, “I think it may be better for 80 people to die so that the local population blames Al-Shabab and hates our enemy than for us to kill one innocent child and have the local population turn against us and side with Al-Shabab.” For me, that is such a powerful moment. That is the one point in the film where now I really don’t know, because if we don’t win the hearts and minds in this war, in my view, we are doomed to escalate this conflict. I worry that that’s kind of what’s happened. We’re escalating. Those are the people that are closest to them on the ground. I do think we should also mention that the Somali actors in the film are refugees from Somalia in Cape Town. The little girl, Aisha Takow, and the man who plays her father, Anmar Hadja, whose own brother was shot by Al-Shabbab, give remarkable performances. Doing this film was a big risk for them, because there is this split between those who reject Al-Shabbab and those who support it. I just wanted to give that moment to them, because those are actors who have never acted before, and I think, in the ensemble, they measure up. You’re not going suddenly, “Oh my goodness, they’re dropping the ball because they’ve never acted before.” I’m very proud of them. I just wanted to say that.

Recently, I was listening to an amazing podcast that followed the life of a young Somali refugee for a year. Those Somali refugees are faced with a tremendous problem right now. What has been happening in Kenya, thankfully not as much in South Africa, is that the police have been harassing those refugees, shaking them down for money. Eventually, some of them go back to Somalia and they join Al-Shabbab, because what are you going to do? You ran from them. And here we have the Syrian refugee crisis. Now I’m getting overly political, but I do think that the film throws up this kind of conversation, and that’s a credit to Guy Hibbert’s script.

Gavin, your body of work reflects a passion for the rules of engagement, the different aspects of war, and the cost of the collateral damage, and asks how does one proceed within that war. Can you talk about how that has been a big part of your storytelling as a filmmaker no matter what story?

HOOD: Thank you for seeing that in a rather sometimes disparate body of work. I think you’re right. I don’t think as directors or writers we necessarily are aware of the theme that becomes our theme when we’re starting out. But having been drafted at 17 into a situation in South Africa where it was morally questionable, to say it without getting into it too deeply right now, and losing one of my friends in the war in Angola, I came to think what on earth was this about. Witnessing the CIA agents out there supporting our side against the other side, because they were being supported by the Soviets, we were the ham in the sandwich of a hot war that the rest of the world called a Cold War. But, it was really a war between those two superpowers for the resources of Africa, and the diamonds, and the oil. I’m 17 and I suddenly had a major political awakening. I don’t feel either proud or ashamed of that. It just happened. But, it set me on a path to questioning, which I am proud of, because you then find yourself saying, “Life is not good versus evil,” or bad choice of phrase, but “black or white. It’s everything in between. How do we reach some sense of our own humanity and not think of ourselves as goodies fighting baddies? I do worry that there is a lot of that in modern film where you take the audience, you identify with the good guy, whatever the good guy does, however many expendables he destroys along the way. As long as he wins in the end, whether it be through violence or revenge, somehow the world is set right. The truth is, it isn’t. It isn’t set right through revenge. It just leads to more conflict and more post traumatic stress. So, I’ve overstated it again, but thank you for finding this struggle. I don’t have a good reason for doing it. It’s just something that entered my world and seems to want to come out in the work that I do.

Helen, you did a fabulous job in this. I felt so guilty because I totally agreed with your character’s point of view and thought, “C’mon, just push the button,” but then at the end of the movie, I felt like, “I’m a monster.”

MIRREN: It was necessary, and it’s a horrendous moral decision, but at some point [you have to make it]. I was thinking of Hitler walking into Hungary and Poland and the way the British, the Americans, the French, and everybody else all looked the other way. Everybody said, “We don’t want war. So don’t let’s have war. War is too horrible.” They unleashed this unbelievable horror for the next five years. At some point, you do need someone who makes a tough decision, horrible decision, hard, brutal decision, but makes it, and in making it saves many, many lives. In the case of Hitler, that would have been saving millions and millions and millions of lives.

HOOD: There’s no easy answer, Helen. But maybe in understanding that there’s no easy answer we can approach the problem with greater humility instead of this dreadful positional bargaining that’s going on. One side is determined that they know everything, and this is not democracy. Democracy is supposed to be let’s examine the problem, which is what Guy’s script does so well and offers us multiple points of view. Then, if we take a life, we understand that we take that life, but because we’ve really thought it through. It’s not that I’m advocating passivism at all. I’m completely with you on this.

MIRREN: I feel the other thing the film does, and maybe people will argue against me, but it actually is a good argument for democracy, because it’s the democratic process of the chain of command and the discussion. Sometimes it’s foolish. Sometimes it’s farcical and funny. But there is that process. It’s not a military dictator that says to do it. There is a sense of conscience and morality, and we know we have to talk this out. Is it legal?

HOOD: But the hawks are pushing for less and less of that. They want less and less of that. That’s fine, but we need a certain accountability. However awkward having that is, it’s what prevents abuse of power, even if it is sometimes frustrating in the boardroom. That’s another whole movie almost.

Helen, what are you working on next that you’re excited for audiences to know about?

MIRREN: I’m about to start working on a film called Collateral Beauty, which is with Will Smith. We’ll be shooting in New York.

Eye in the Sky opens in limited release March 11th.