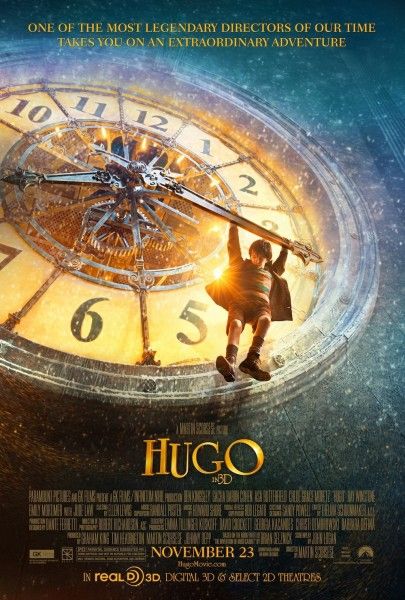

The most talented directors find a way to use their cinematic influences in order to build a new story, and then let the audience seek out those influences. It's a rewarding experience because we can see how well the director used the earlier work of other filmmakers, and then we seek out that work for ourselves, which in turn expands our knowledge and understanding of cinema. Martin Scorsese is one of the most talented directors of all-time and has always proved a master of layering in his inspirations without ever overtly referencing them. He leaves that direct reference for interviews where his infectious energy and enthusiasm shows that if he wasn't a legendary filmmaker, he'd be a legendary film professor. However, that energy and enthusiasm doesn't translate to his new 3D movie Hugo where he moves his love of movies from subtext to text, and turns a child's adventure story into a lecture on the importance of cinema pioneer Georges Méliès.

Set in 1920s Paris, the story follows young Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield) who secretly lives inside a train station after the death of his father (Jude Law). Hugo's daily adventures include swiping food to survive, avoiding the watchful eye of the crippled station inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen), and trying to steal machine parts from Papa Georges (Ben Kingsley) who operates a toy shop inside the terminal. While the movie opens with a long, sweeping shot indicating that Scorsese is about to have some serious fun with the 3D, matters quickly turn grim as our first meeting with Hugo has him getting caught red-handed by Georges and then getting his precious notebook confiscated. Hugo tearfully asks for it back, but when he won't explain where he got it from, Georges says he's taking the notebook home to burn it. Hugo has a tough time finding its footing when we enter with the visual wonder of the train station only to be hit moments later with a Dickensian encounter.

From this point onward, the film tries to serve two stories that should work hand-in-hand. One story is the adventure of Hugo teaming up with Georges' god-daughter Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz) to get the notebook back and unlock the mystery of an automaton he received from his father. But the larger story is about Scorsese's real interest: the magic of cinema. Scorsese never neglects the adventure or the mystery, but it seems like he believes his love and unwavering belief in movies will sprinkle down like fairy dust and enchant Hugo's story.

Looking at how Hugo is built, that approach should be a success. The movie has an incredibly smart subtext about deriving the magical from the mechanical. For Scorsese, 3D was essential to telling this story not only because of the visual wonder he could pull from the technology, but because it gives him a line all the way back to Méliès. Méliès was originally a magician, and then he discovered the technology of cinema, built his own camera and studio, thus combining magic with cinema and eventually to Martin Scorsese. Hugo is Scorsese paying it forward by trying to show kids today how the magic of the cinema they love comes from the magic Georges Méliès created at the dawn of cinema.

In theory, the delivery method of wrapping this lesson in an adventure movie should work. It should be an absolute joy to see Hugo and Isabelle running through a gorgeously realized environment filled with classic architecture, golden gears, and secret passages. The mystery involves a mechanical man, a key in the shape of a heart, and hidden messages. It's a set-up that both kids and adults should love.

"Should." That's the word that best applies to Hugo. As the end credits rolled, I sat in my seat and was dumbfounded at why the film left me so cold. It speaks to my love of cinema, has a great premise, the performances are solid, the visuals and 3D are spectacular, and it has a thoughtful subtext running throughout. It wasn't until I discussed the movie with my peers that I finally began to understand why Hugo should work but it doesn't.

There are some elements where the shortcomings are readily apparent. John Logan's script is bogged down in clumsy exposition and manufactured conflict like when Hugo won't simply tell Georges, "I got the notebook from my dead father and it's precious to me." There's so much sorrow that at one point Isabelle has to stop and tell Hugo that's it's okay to cry, which is good because he does it a lot. It's tough to care if the station inspector finds love with the florist (Emily Mortimer) because he seems to take such glee in sending helpless kids to the orphanage. The movie mistakes nastiness for danger and further undermines the notion that Hugo is a first and foremost an adventure story.

But the main reason the adventure fails to come alive is because Scorsese has turned his love of movies from subtext to text, and it makes Hugo feel like a lecture. It's a thoughtful and intelligent lecture filled with gorgeous visual aids, but we're no longer in theater. We're in a classroom. Scorsese is trying so hard to capture the magic of Méliès, bring that magic to a modern day audience (Hugo is filled with clips from Méliès' movies), and then explain why that magic is magical. If you were to watch a documentary where Scorsese talked about Méliès for over two hours, it would probably be fantastic. But having him try to do it through a kids' adventure film drains the story of its wonder and makes his points feel heavy-handed.

Scorsese's approach to a kids film is assuming that if he fills the movie with the veneer of a grand adventure, colorful visuals, and a goofy station inspector (who actually comes off as more cruel than buffoonish—the character is stuck between Buster Keaton and a Charles Dickens villain), then an audience of children will have a grand old time. But instead the effect comes off like a grandfather handing his grandchildren a copy of A Trip to the Moon and then explaining why they should love it.

I'm left to wonder why Scorsese chose to make overt references to Méliès when he could have made a more graceful and captivating movie if he hid those references within the context of a larger, more accessible story. When the music video for The Smashing Pumpkins' "Tonight, Tonight" was released in 1996, I had no idea it was based on A Trip to the Moon. I simply liked the song really dug the music video. It wasn't until I was older that I learned about the inspiration for the music video and that original appreciation carried over to A Trip to the Moon and made me want to see Méliès' other films. That won't happen to kids who see Hugo because Scorsese makes the adventure serve the lecture, and the movie will only enchant 10-year-old cinephiles and those who feel like an ode to Méliès' is its own adventure.

Rating: B-