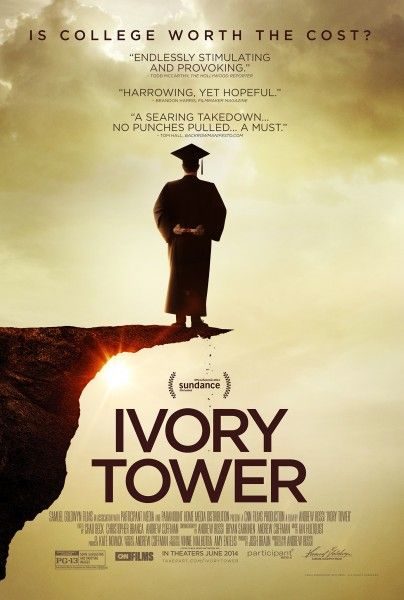

Filmmaker Andrew Rossi pulls no punches in his provocative and engaging documentary, Ivory Tower, as he examines the state of higher education in America and reveals how leading institutions have lost their way in the struggle to remain competitive. Rossi asks if the pursuit of higher education is worth the staggering cost and if it is possible to evolve a sustainable economic model that still offers the potential for life-changing college experiences. Opening June 13th, the film profiles an impressive array of schools with different ideas and approaches including Harvard, Stanford, Arizona State, Cooper Union, Deep Springs College, Spelman College, and online education company Udacity’s pilot program at San Jose State.

In an exclusive interview, Rossi spoke about what inspired him to explore this issue, how he decided which people and institutions to focus on, why he shuttled between contemporary profiles and historical context to tell the story, the paradigm shift in popular sentiment toward viewing higher education as a private rather than a public good, how institutions have evolved into business models that treat students as customers and profit centers and promote expansion over quality learning, the growing doubt about the value of a degree, the future of traditional brick-and-mortar versus online education, and his upcoming project on mental illness. Hit the jump to read the interview.

QUESTION: What inspired you to make a documentary about this particular issue: the staggering cost Americans are facing in the pursuit of higher education?

ANDREW ROSSI: All the films that I’ve made have looked at institutions that are facing great disruption or are at the crossroads of change. I looked at the newspaper industry with Page One: Inside the New York Times, the dining world with Le Cirque: A Table in Heaven, and same-sex marriage with The Sky Did Not Fall. When I finished Page One, I was looking for another important cultural institution that I could focus on, and this was the time when student loan debt just exceeded a trillion dollars, and Peter Thiel was announcing his program to basically pay students to drop out of school. As somebody who on a personal level had a very rewarding experience in college about 20 years ago, I wondered how things have changed and what might you find if you brought cameras on campus and were on the ground. What would we see is happening to students and faculty? That was the seed of the idea. We started shooting at Harvard first, and then expanded to Arizona State University and Spelman College, and it just took off from there.

Your interview subjects range from university presidents and academic administrators to the California governor and students attending a diverse array of colleges and universities such as those you just mentioned. How did you decide which people and institutions to focus on?

ROSSI: We wanted to find schools that reflected the fullest representation of a particular idea or approach to higher education. In the case of Harvard, we’re looking at the first university in America, one that has such a huge endowment that they’re able to provide amazing financial aid, and they’re on the cutting edge of technology in classroom instruction. As Clayton Christensen (Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School) says in the film, they provide the DNA of higher education that so many other institutions are trying to follow and model themselves after, even though they don’t necessarily have the endowment that Harvard has. We wanted to look at what problems might arise when schools try and continue to grow as large and as complex in terms of the facilities they need to have to provide a product that can come close to what Harvard provides. And then, on the opposite spectrum, you have a school like Deep Springs, which is such a great example of students in a small program in the middle of virtually nowhere in Death Valley and has a totally different approach. Arizona State University also is another very extreme example of a non-selective admissions school in the sense that they admit students on different criteria than a school like Harvard does and consequently have the largest undergraduate enrollment of any other college or university in the country. Certainly Spelman is another very intense experience for the students who are there. They have an almost spiritual experience as part of this black college that was founded just a few years after the end of slavery. There is such a clear sense of mission there. That ultimately is what we wanted to capture. It’s when schools have a very clear sense of mission, how do they do? What’s working and what’s not working? And then finally, Cooper Union is a school that unfortunately has lost the sense of their mission.

How did you cut through the typical marketing points that universities use to shape how their institutions are perceived by the public to get at the truth?

ROSSI: It took a lot of research and we read. We had a research team and we went through as many of the cutting edge studies that we could find. When we were interviewing some of these administrative heads or leaders, we tried to not pull any punches and ask them how the marketing points that they have gel with some of the statistics that can be found in these studies like Academically Adrift or Paying for the Party. For example, even in the case of Massive Open Online Courses, MOOCs, [we looked at] how some of the results from Udacity’s pilot on San Jose State’s campus worked out.

I liked how you showed the history and the concept of higher education in America and its development and evolution over the past few centuries. Can you talk about the storytelling approach you used to shape your documentary to make it informative as well as engaging?

ROSSI: We felt it was important to explain to contemporary viewers the extent to which our popular conception of college has changed over time and how historically higher education was viewed as a public good, as something that the government should support with the Morrill Act of 1862, the G.I. Bill, and the Higher Education Act of 1965, and how all of that shifted in the 70’s and 80’s when you had conservative governors who felt that intellectual curiosity should not be subsidized. And so, even as we see all these searing portraits of partying on campus and the perverse incentives taking place in the classroom in certain schools, we wanted to then on a periodic basis throughout the film harken back to when higher education was a much simpler product to be delivered and one that was supported with an almost moralistic sense of mission. So, the approach to the storytelling was to be able to shuttle back and forth between contemporary profiles and that historical context.

Higher education has undergone a lot of change as more and more of society is viewing education as a way to make money rather than as an opportunity for rewarding personal growth. What do you feel is responsible for that paradigm shift?

ROSSI: I think the key is that shift in the popular sentiment toward viewing higher education as a private good versus a public good and focusing on whatever wage premium graduates might have. Even this Tuesday, there was an article in The New York Times by David Leonhardt which seeks to prove that college is always worth it, because over the course of graduates’ lives they will earn much more than those that only had a high school diploma. But even though that is true and those numbers are powerful, they do not include a host of other factors that one needs to think about when they decide whether or not to go to college and which college to choose. It doesn’t necessarily mean that any school one goes to will be the right fit and will be the right place for them to go. It depends on what they’re studying, how much student loan debt they’ll be incurring, and also whether they’ll finish, whether they’ll complete. One of the most striking data points that I encountered while researching the film was the fact that 68% of students at public universities don’t graduate in four years. That’s a troubling statistic.

Cooper Union incurred immense debt to build a new addition to their campus and then made the controversial decision to charge tuition to solve the budget shortfall despite the fact their institution was founded on the ideal of free education to all. Why have colleges lost sight of their mission to educate young people in the struggle to remain competitive?

ROSSI: I think that there is a complex set of perverse incentives at work. We see the university growing more and more like a business that treats students as customers, particularly because the tuition rates are so high, that in order to attract students they need to be aggressive in persuading the student that their school is the one where the student will have more fun or have a better experience, where the sense of what that experience is keeps on veering towards social life and non-academic perks.

What are your thoughts on the growing doubts about the value of a degree versus the importance of education for fostering positive social change, mobility and economic growth?

ROSSI: I think that the idea of college endures as the great gateway into the middle class and as an engine of social mobility. But we also see that college can become almost a way to launder inequality, which is sort of a quote from Anthony Carnevale (Director of the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce) in the movie. It’s something that he gets into. It’s a calculated calculus, but basically, college has become so important for certain jobs that if you don’t go to college, it can actually prevent certain people from getting certain forms of employment. And then, in another way, if one does go to college and emerges with so much debt that is paralyzing, it can also solidify class difference.

Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren commented that we need to stop treating students as profit centers because of the exorbitant rate that’s being charged on student loans. Do you think America has an obligation to provide young people with access to a reasonable cost education? And if so, what has to change to make that possible again?

ROSSI: I do think that Americans need to think very hard about what their priorities are, and I suspect that higher education is at the top of many people’s lists. We need to start a conversation about getting the cost of college under control and trying to figure out how to reduce student loan debt. There are some state-based initiatives all across the country, but there needs to be a bigger national conversation. It’s a great thing that President Obama has suggested that there should be rankings of schools, not because rankings are a good thing per se. I think that they can actually be very problematic, but at least it’s putting attention on student loan debt amounts and completion rates when students and parents are assessing what school their child should go to. For instance, which one has the best football team or new dorm?

What is the future of traditional brick-and-mortar education, and also what are your thoughts on online education and its ability to transform higher education and address this kind of runaway cost?

ROSSI: There is a lot to be excited about with Massive Open Online Courses and the ability of technology to increase access and lower costs. But also what the movie clearly shows is that some form of in-class instruction is necessary. So, there is a place for the brick-and-mortar experience in terms of the peer-to-peer interaction that students would have and the encouragement and guidance that they can have from teachers. But there definitely are ways to cut costs while using technology.

What role do you hope this film will play in terms of raising awareness?

ROSSI: On the most immediate level, I hope that the parents and the students who go to see the movie will emerge with a more nuanced idea about how they should pursue higher education. On a broader level, I hope that it becomes a tool for policymakers and others to basically educate everyone about what is at stake with higher education.

What was the most personally rewarding aspect of your filmmaking experience?

ROSSI: I would say the most rewarding thing is after screenings, which we did one today and we did another one last night. I’ve had students come up to me on the verge of tears saying, “Thank you so much for making this film. I have X amount of student loan debt, and no one understands what I’m going through, and this movie made me feel like somebody was listening.” And then parents, I just had one today who said that her son studied at a private university, but then dropped out and now is a carpenter and wishes that he hadn’t gone to school to begin with. When he went, there was really no conversation about the validity of a choice to not go to college, that there’s such a reflexive assumption that anyone who is successful in high school is automatically going to go to college, and that she wished that this non-college movement had been around previously. It’s hearing those stories, and speaking with people, and seeing them touched by the film that’s the most rewarding thing.

What are you working on next that you’re excited about?

ROSSI: I’m developing a project on mental illness for participant media, and we’re just in the early stages of it, but hopefully it will be a film that looks at different ways to reduce the stigma that’s associated with mental illness and to tell a character-based story in that world.