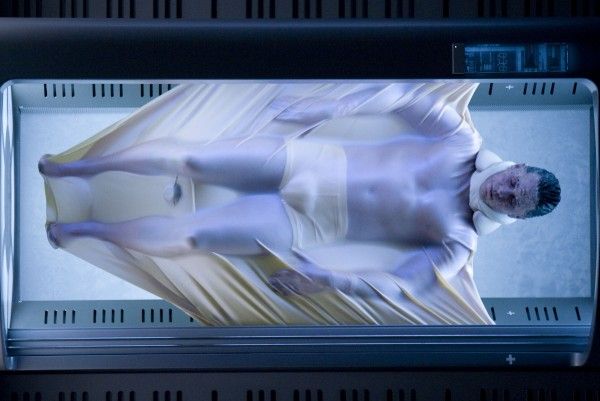

From writer/director Jaco Van Dormael, Mr. Nobody is a beautifully artistic film that explores the infinity of possibilities that rise from each decision in life. In the year 2092, 118-year-old Nemo (Jared Leto) talks to a reporter about three primary points in his life -- at 9, when his parents divorced, at 16 and at 34 -- but he tells of alternate life paths, often changing course with each decision, at each of those ages. The film also stars Sarah Polley, Diane Kruger, Rhys Ifans, Juno Temple and Toby Regbo.

During this recent exclusive interview with Collider, Belgian filmmaker Jaco Van Dormael talked about the 10-year process of making this film, finally making it more accessible for American audiences, what inspired the ideas in this story, not worrying about how audiences will react to his work, what made Jared Leto the perfect actor to carry much of this film, and how the next film he’s written is about God. Check out what he has to say after the jump.

Collider: It’s clear how much time, effort and passion went into making this film. What’s it like to know that audiences in America will finally have more access to it and get to see it, after so many years of trying to make that happen?

JACO VAN DORMAEL: Yeah, it took me 10 years to make this film. It took six years to write, and two years to do it, with six months of shooting and a year and a half for editing and sound. The whole process was about 10 years. What took me the most time was writing, but that’s normal. The most important part is the script, the writing and the words. It’s also less expensive, so I spent a lot of years on that. I’m a slow writer.

Has it been frustrated that more people haven’t been able to see it, or are you just happy that it’s more available now?

VAN DORMAEL: I’m glad that the film has finally arrived in the States, after four years. It also took four years to be released in Korea. I think that’s the same time it would take a message dropped in a bottle to arrive. For my next film, I’ll just put a DVD in a bottle and drop it in the water. It’s great because it’s a film that’s a little out of time. It is a strange film with a strange journey, and the film itself has had a strange journey. It doesn’t resemble other films, and it represent the way most films are released.

How did this film start? Did you have specific themes and ideas that you were looking to explore, and then it developed from that, or do you start with specific characters and develop the story from there?

VAN DORMAEL: I made a short film in ‘82, called È Pericoloso Sporgersi, and it was a 12-minute story of a boy who had two lives, one where he went on the train with his father and one where he stayed in the station with his mom. When I went back to that idea, I realized that, after one bifurcation there was another bifurcation, and then another bifurcation. The complexity of what makes a choice impossible is perhaps because, every time you make a choice, there is an infinity of possibilities. If you make the other choice, there is also an infinity of possibilities. When you have the feeling of making a free choice, is it really free, or is it because of my fears or because of my background or culture? When I fall in love, I don’t know why I fall in love, I just know that I am in love. I can’t fall in love with a door or a telephone, so where is the freedom in the choice? Is the freedom just in saying yes to a person without knowing why? That is a question of complexity.

There is a big difference between storytelling and being alive. Those are the two things that I prefer in life – telling stories and being alive. In stories, everything has to have clear consequences and everything has to focus to the end. Everything at the end will give meaning to everything that precedes. In my own life, the consequences of the choices I’ve made aren’t always very clear. The most beautiful things are sometimes not totally truthful, and the end will not give more meaning to everything that precedes. So, the writing was about how to speak about the absence of story in life, and to tell it in a way where it looks like a story. Instead of focusing on the end, it’s more close to a video game where everything is going in all directions, at the same time. That’s the reason why the script took so much time to write. I had to invent the structure, differently from everything I’ve done before.

When it takes so many years of your life to write, direct and put the movie together, were there ever any moments where you thought you should just move onto something else, or were you determined to make this film, no matter how long it ultimately took to make?

VAN DORMAEL: If you’re not compulsively a monomaniac, you’ll never make a film. It’s like taking the same chewing gum, every morning, and saying, “Okay, it has a lot of taste,” and continuing to chew it. After six years of writing, if I stop, it’s something that will never happen. But, it was really fun. The whole process was 10 years of happiness.

How much different is what we see now from what it started out as? Does it feel like the story and ideas in it changed and evolved quite a bit, or does it feel close to what you first envisioned or wanted for it?

VAN DORMAEL: The film is totally close to the script because all of the transitions had to be written. What is different from the script is that it’s a collective piece of art. When I write, I speak with ghosts for years, and I see images that are a little bit out of focus. I see faces, but the faces change. At the moment that it’s a real human being that’s flesh and bone, it changes a character. It’s much more precise and complex. And then, there’s the camera with that lens and the set with that color. And everybody on the crew brings something that is indispensable and adds to the complexity of the feeling that you can have. It’s not a dream anymore. It looks like a dream, but it has a lot of details.

Were you ever concerned that American audiences might not fully understand some of the more surreal moments in the film, or is it more about the experience and the emotions of it than it is having the audience fully understand every moment and details of the story?

VAN DORMAEL: I never worried about it because it’s a little bit like that moment you are lost, but then you find the way out. I never know what the audience will think. I don’t know what the people who loved the film have seen, and I don’t know what the people who don’t like the film have seen. I will never see the film myself because I know it like my pocket. That’s something very mysterious. A film is like a message dropped in a bottle in the sea that somebody finds. Every time somebody finds it, it’s a miracle. But, I don’t know what the perception will be. I can know what I tried to do, but I never know what the perception is. The film is very simple. It resembles the way we think, with multiple possibilities. It’s like having a phone call while, at the same time, having a conversation on the computer while, at the same time, watching a film. A non-linear narrative is something that you can enter very easily, jumping from one story to another.

The role of Nemo must have been challenging to cast, with so many different versions that each have their own look, mannerisms and physicality. What was it about Jared Leto that made him the perfect actor to take on that role?

VAN DORMAEL: I think Jared was really the perfect actor for that role because he’s an actor of transformation. He’s somebody who likes to make characters that are very far from himself. When I realized, in his filmography, that he was in two or three films that I’ve seen but didn’t recognize him in, at that moment, I was sure that he would be the perfect actor to make nine different Nemos in nine different lives. Of course, he’s helped by the costumes, the make-up and the hair-cut, but he does it from the inside. He had different breathing and different voices. At the same time, the way we filmed all of the nine Nemos was very different. For life with Elise (Sarah Polley), the camera was on the shoulder the whole time and not stable. When he’s a widower, the camera is far from him, like he’s far from himself. We never follow him. The camera is very independent. It moves to see something else, and then comes back. The camera helped to make each of the characters different.

Were there things that Jared Leto brought to the character, as an actor, that you hadn’t envisioned before casting him and watching him perform?

VAN DORMAEL: Of course, yeah. That’s the miracle. It’s impossible to really imagine what is flesh and bones. Only an actor can do that. It’s so much better when it’s slightly different from what I thought it could be. There are more complex feelings and perceptions. An actor can play two or three lines where he says one thing, but plays the opposite. That’s the most important moving part of a film.

What was it about Diane Kruger and Sarah Polley that led you to cast them?

VAN DORMAEL: Sarah was really my first idea for Elise, and she said yes, immediately. The first time I met her, I asked, “Can you cry for two weeks in a bed without suffering?” And she said, “Oh, no problem! I can cry and stop on command. I will not suffer to do that.” And that was really true. She’d say, “Give me 10 seconds, and I will be in the character.” She would take 10 seconds and cry, and then when the camera would stop, she was laughing with everybody. She’s really a fantastic actress. She’s also been an actress since she was six years old, so she knows how it works. And Diane was really fantastic, too. She was playing a character that’s very different from what she plays, usually. What she did really well was to reinvent the love of two children with the same power as first love, and she did that fantastically well.

Do you feel like having a big budget for this film worked to your advantage, or do you also like the idea of having to get more creative when you’re working with a tighter budget?

VAN DORMAEL: Having a big budget, I have no problem with spending the movie. It’s fantastic to have a big budget. It gives a lot of time. It gives a lot of freedom. What’s difficult is raising the money beforehand, and then when the investor wants the money back, afterwards. Because nothing is really realistic, and everything is more about the perception, it looks true and not true, at the same time. All the special effects were there to say, “Perhaps this is not the reality.” That’s more expensive than having something realistic. Perhaps for my next film, it will not be as big of a budget, and more into the reality.

Where do you go from here, as a filmmaker? Do you already know what you’ll be doing next? Are you currently writing something now?

VAN DORMAEL: I worked for two years on a theater play that’s not really a theater play. It’s a film that is made on stage. It’s a 20-minute film that is directly made on the stage. It’s called Kiss & Cry, and we’ve played in Boston and Pittsburgh. That is much more collective. It’s got tiny sets. I said, “Is it possible to make a feature film on the table in the kitchen, just to make it differently?” And it’s possible. That is something that we played 150 times, and it was really fun to do. And I wrote a new script that I will shoot next summer, and it’s about God. If God exists, he lives in Brussels with his wife and young daughter. To take revenge, his young daughter puts secret information on the internet and has to escape. It’s shot very naturalistic.

Mr. Nobody is currently available on VOD, at iTunes and on Blu-ray/DVD, and will be in limited theatrical release on November 1st.