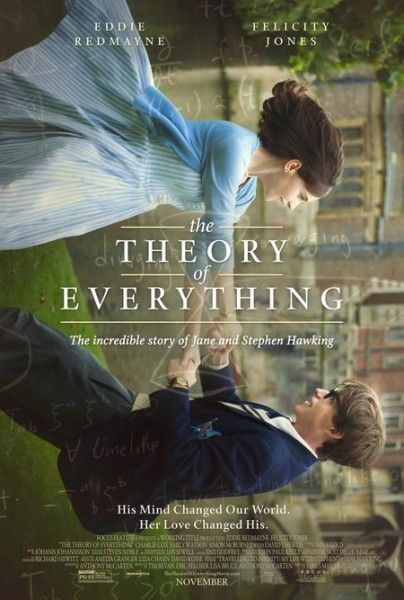

Following a screening this week of The Theory of Everything, the entertaining biopic about brilliant cosmologist Stephen Hawking, I participated in a cool Q&A with the film’s Oscar-nominated composer Jóhann Jóhannsson whose score recently won the Golden Globe Award and also received BAFTA and Critics’ Choice nominations. The drama stars Eddie Redmayne as Hawking and Felicity Jones as his wife, Jane Hawking, and is based on her memoir of their life together, Travelling to Infinity. In addition to Best Original Score, the film has garnered nominations in a number of other categories including Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor and Best Actress in a Leading Role.

Jóhannsson discussed his collaboration with director James Marsh, his approach to scoring a film with a love story at its core, doing justice to the scope of the film, the organic process of finding the right sound, his focus on an orchestral expression using piano, strings and processed acoustic sounds, his interest in voice synthesis and vocoders, dealing with a delicate subject without tipping the balance into sentimentality, how Hawking’s A Brief History of Time served as inspiration, the most difficult sequence to score, the international nature of filmmaking today, why he enjoys being based in Berlin, his Icelandic musical influences, and his next film project: Denis Villeneuve’s Sicario.

Congratulations on the Oscar nomination. You were at the Oscar luncheon today. What was that like?

JÓHANN JÓHANNSSON: Yes, I was. It was amazing. It was really a wonderful event and quite spectacular. It was a very special afternoon.

How did this film come to you? Did you know director James Marsh or had you worked with any of the filmmakers before?

JÓHANNSSON: Yes, I did know James. We had met. We both lived in Copenhagen. I lived there for seven years and I met him there because he was a consultant on a documentary that I scored in 2009. So, we met and he became familiar with my music. We kept in touch, and several years later he got in touch with me about this project.

I’m curious to know about how you began. This is a story about a theoretical physicist. It’s also a very private story about a couple whose marriage eventually falls apart. Can you talk about how you approached the subject?

JÓHANNSSON: It’s very much a story about relationships and a love story at its core. That was the most important aspect of the film to capture, underline and support. The emotional element and the love story were the most important things. The performances were initially something that was very inspiring and that sparked a lot in me when I first saw the rough cut, Eddie’s (Redmayne) transformation, his amazing performance, and the dialogue and interplay between him and Felicity (Jones). The chemistry that was between them was very strong material for me to work with and to use as inspiration. Another challenge was to do justice to the scope of the film because it has a fairly large scope. It spans decades and it’s the story of a man’s life. I had to give a sense of the passage of time and to have this variety and this sense of time while having also a unity of style and unity of teams, so that the music has a sense of unity while having a lot of variety as well, and also being timeless in a way as well in the sense that it’s not connected to a particular period.

You didn’t have a sense that the music should tell us we’re in the 1960s or the 1970s?

JÓHANNSSON: No. The music had to exist out of time in a sense, so that was definitely a challenge.

How did you decide on the sound of the score? There’s a lot of strings and piano. Can you talk a little about those orchestrational choices?

JÓHANNSSON: The piano was a very early choice that felt very natural and maybe came just from the first demos that I did which were piano-based and seemed to work very well. Also, the piano is a very expressive instrument, but it’s also very precise and has this precision to it, and there’s almost a mathematical quality in some way. It has that kind of resonance for me at least. So, the piano was an early choice. It turned out to be a purely orchestral score for the most part. There are some electronics in there but they are quite fairly well hidden and they’re confined to only a few cues. Most of the score is just an orchestra performing in a room, which is fairly rare for me. I usually tend to combine the orchestra with electronics, and to process quite a lot, and to spend quite a lot of time after the recording processing recordings and creating this more intricate sound world. Whereas this score is much more of a pure orchestral expression, and that was a new thing for me and something that I enjoyed doing very much.

Was there any communication with the director to encourage you to use more electronics in the score? Or was he very pro-orchestral sounds exclusively?

JÓHANNSSON: There were no real directions in terms of that. We had a vague idea in the very beginning of the score becoming more electronic through the film as Hawking’s movement became more and more restricted and his illness progressed. But that idea was fairly quickly forgotten. In the end, the electronics are mostly in the scenes in the hospital and in the coma scene. They’re not really electronics. They’re actually just processed acoustic sounds. There are no synthesizers. It’s all acoustic sounds, but there’s some processing going on in those particular scenes. It’s very subtle. So, it has a very, very orchestral feel. It’s interesting, for example, when he gets his voice synthesizer. That was a really interesting challenge to write around that voice because it’s

a very distinctive voice, very iconic, which everyone recognizes. It has this great authority, this almost oracular kind of quality. It was a lot of fun to write around that. In my solo work on my own albums, I have used voice synthesizers and vocoders quite a lot in connection with orchestral instruments. I don’t know, maybe that was also at the back of James’s mind when he approached me for this score. This is something that I’m very interested in. I’m very interested in voice synthesis and vocoders in general.

This subject matter requires especially careful handing. We’re dealing with the idea of a serious illness and what earlier on we’re led to believe is going to be a death sentence. And yet you don’t want to tip the balance into sentimentality. Can you talk a little bit about the kind of balance that you had to strike?

JÓHANNSSON: This was something that James and I discussed quite a lot and that we both felt was a very important thing to consider in writing the score, too. The music had to underline the emotion, and it had to move people, and it had to have an emotional resonance. But it’s easy to take things too far, and if you lay it on too thick, the magic disappears. It’s about keeping exactly the right level of emotion. This is something I work and struggle with a lot in my music, because my music tends to be quite emotional and it tends to be quite expressive. But I’m very interested in restraining this expression as well. So, there’s this sort of expression that is restrained, because I think the emotion becomes stronger in a way if it’s reined in.

Were there early demos that you did that maybe went too far, and did you and Marsh experiment at all?

JÓHANNSSON: No, I think I was probably too restrained to begin with and was encouraged to let loose. We arrived at this together. A lot of it is also about placement, where to place the music, and where not to have music, and where not to score. I think that’s almost as important as where to score.

Do you have to go through the usual process of mock-ups and approvals or were you playing piano demos?

JÓHANNSSON: No, no. I always do very detailed demos. I feel that it’s better to show the director a demo that sounds as close to the final thing as possible with samples. It takes time to create, but I feel that it’s better to get the director on board very early on in terms of the sounds that I have in my head. So yes, the demos are always very detailed.

What part of your mock-up becomes part of your orchestration? Do you orchestrate it and then find the samples or are you doing it all at the same time?

JÓHANNSSON: I would say the midi orchestration and the writing and the final orchestration all happen more or less at the same time. It’s an organic process that just develops. I mean, it certainly happens that I write something at the piano at home and then I sit down and orchestrate it, but very often it’s sort of an organic process of just finding the sound. Of course, once you’ve established the sound with the first couple of cues, you have a template. You basically have the toolbox you need and then it becomes a lot simpler. You just establish your own rules. These are the instruments I’m using. These are the instruments I’m not using. Then it just becomes a process of using that toolbox to build the score.

Did you read any of Hawking’s books when you got the assignment?

JÓHANNSSON: I was familiar with A Brief History of Time which I read in college years ago. I reacquainted myself with that book. I didn’t read the whole thing again, but I read some of it just to get a sense of his voice and a sense of his writings. I used a lot of his titles and phrases from his books in the titles of the cues on the soundtrack album. He has a very lyrical, poetic, accessible way of writing about physics, cosmology, and the universe. There’s a lot of poetry there.

Did you find any of that inspirational?

JÓHANNSSON: Absolutely. I think we tried to capture that in some sense. There are a few scenes where he’s at the blackboard, and in the lab there’s a largely wordless scene where we tried to show a sense of wonderment, mystery, and amazement for the complexities and infinite mysteries of the universe that fascinate him and to get a sense of his longing for this simple, beautiful equation that explains everything. There are a couple scenes like where he’s stuck with his sweater over his head and has this epiphany staring into the fire. That’s where maybe we tried to approximate the poetry of physics in some way.

I was reading the album credits and I noticed that you recorded most of the score at Abbey Road but the pianos at AIR Studios. Why was that?

JÓHANNSSON: There was a scheduling and booking issue. I would have very much liked to record everything in the same room, but Abbey Road was not available for the piano session unfortunately.

How long did you work on the score? Did you have months to work on this or was it a fairly short schedule?

JÓHANNSSON: It wasn’t a very long schedule, but it wasn’t very short either. I think we started late January and we recorded the end of May, but I was not working on it all the time. I was doing another project as well. So, it was about three months.

When you’re given a two-hour film, how do you approach scoring an entire piece like that? Do you start from the beginning and work to the end? Do you plan out how much you have to write? Do you budget your time?

JÓHANNSSON: I tend to start by finding a key scene or a couple of key scenes to work with, and to identify scenes that are somehow integral to the film, and to attack those first and to try to crack those scenes in some way. The hardest part of writing a score is always finding that first idea and the voice of the film, the sort of melodic, thematic and sonic identity of the film. You always spend, or at least I always spend, a couple of very frustrating weeks, sometimes more, trying to find this. In the case of this film, it was really the very first scene which came first. I attempted the lecture scene first and I did a demo for that which didn’t work. Then I went to the very beginning and wrote the piece basically that you hear.

That became the first piece of music that I wrote for the score. That also became the source of a lot of the subsequent material like this four-note ostinato that the film begins with, which is woven into this certain pattern that explodes into a very kinetic, vigorous, dynamic piece of music in the beginning. Both that ostinato and the harmonies that I lay over it are used in subsequent cues and developed throughout the whole film. For example, in the final, climatic scene where he delivers this triumphant lecture and has this sort of mystical moment when he rises up from his wheelchair, that’s basically more of a philosophical, more serene, thoughtful version of the opening theme. So, it’s really about finding this first idea. Once you have that, the rest is just fun really. About budgeting time, I don’t know. I just work all the time. I don’t really take vacations.

What was the most challenging scene you struggled with in this film?

JÓHANNSSON: There was a scene which was a fairly long sequence, sort of a montagy sequence which starts with the Brian character carrying Stephen up these stone steps. Then the scene moves to his house where he gets his first electric wheelchair. Then there’s an idyllic montage in the garden with his son where he’s turning around in circles. Then it’s followed by several other scenes culminating in a very chaotic domestic scene where we see Jane’s frustration with the domestic situation and with her inability to cope with his increasing disability and the whole familiar situation.

It’s a scene that goes through a lot of different moods. It starts very joyfully and comedically, goes through this idyllic stage, and then ends where it sort of curdles and becomes quite sour and a little bit bitter. It was quite tough to navigate that whole sequence and write a piece that again had a melodic and thematic unity, but still somehow underlines this whole emotional journey and all this information that you are given in this sequence, which is a lot of information. A lot of different aspects of their life are basically revealed in this sequence. That took several attempts and it began as something much more complex. I had five or six different sections, and it ended up being two different sections, but with variations obviously.

I know there are a lot of composers who have had their ups and downs with temp tracks. Was there a temp on this film, and if so, was it helpful or were you able to get rid of it early on? Can you talk about your experience there?

JÓHANNSSON: Yes, there were so many temps in this film, but James has a very sensible approach to using temps. He uses them as a very rough guide to rhythm and as an aid in editing. A lot of the temps were mine. Actually all the pieces were mine, which is not necessarily any better. It can be worse if anything. But it’s not something that I have a huge problem with. It’s just a reality of filmmaking. I tried to put them out of my mind as quickly as possible and tried to get a sense of what [was needed]. Often a conversation with the director helps to pinpoint whether it is through simply the rhythm, or if it’s a mood, or what it is in the template that they’re interested in, or why they made that choice. And very often it is something that is very quickly forgotten. There were certainly no temps that I had to struggle with in this case.

Before you had a locked picture, were you working on themes?

JÓHANNSSON: They didn’t really lock it until the second day of recording.

Is there no such thing as a locked picture anymore?

JÓHANNSSON: No, not really. But they were not changing big things. Certainly I had to make some edits after recording as well. They locked it progressively. To be fair, they locked the key scenes fairly [early]. We were just in a dialogue about that. I said, “Hey guys, I have to orchestrate this. Can we…?” Then we locked that scene and that reel. They were definitely making changes pretty much until the end, so it was a fluid process.

When you’re composing, are you composing to the picture or are you composing to those rough cuts?

JÓHANNSSON: To a rough cut.

Did you work with a music editor?

JÓHANNSSON: There was no music editor on this picture until very late. In the final two weeks, we had a music editor.

There’s a wonderful piece at the end of the album called "The Whirling Ways of Stars that Pass". It seems to be a solo piece for harp. It’s just a beautiful piece that concludes the album. Is it in the film anywhere?

JÓHANNSSON: Thank you. Yes, it’s in the end credits. It’s the very last piece.

It’s so rare that we get a solo piece for harp anywhere anymore in films. It’s a lovely choice.

JÓHANNSSON: You can get away with it at the very end of the credits.

It’s been this amazing whirlwind over the last three months where you’ve been talking about the film, you won the Golden Globe, and now you’re nominated for an Academy Award. What’s that been like for you?

JÓHANNSSON: It’s a bit surreal and strange and wonderful. It’s great to be recognized for your work. I think everyone likes to be recognized for what they do. Everyone involved in this film is really proud of it. It’s great that the film as a whole is being so well received both by audiences and critics and that our work is getting this recognition. It’s teamwork. Filmmaking is a collaborative art and it’s all about the team. I’m lucky enough to be involved in a project that basically involves a lot of very, very talented people, which makes my music sound very good.

You finished this at least six months ago. What else can we expect from you? Have you finished other scores in the meantime for films that will be coming out? Or are you working on anything now that you can talk about?

JÓHANNSSON: Yes, I’m actually in the middle of finishing a score for a film by Denis Villeneuve called Sicario. We did another film called Prisoners last year. This is his new one. I’ve finished writing it. I’m in the process of orchestrating and preparing for recording which will happen in a week’s time. Then I will come here and mix it here, and go to the Oscars, then go back to finish mixing, and then go home.

You seem to epitomize the international nature of filmmaking now. You’re Icelandic by birth. You worked in Denmark for a long time. You’re now based in Berlin. You recorded in England. Can you take us on this odyssey where you’ve been?

JÓHANNSSON: I think these days it’s easier to live as a composer where you feel most at home and where you feel you have people around you that you can work with and that are supportive and creatively inspiring. I found that in Berlin. I found a really great community of musicians and composers there that I feel really a strong sense of affinity with. Berlin is a very creative city and Copenhagen as well. Copenhagen was a really wonderful city to grow especially as a film composer. I did a lot of projects there, mostly documentaries and one or two fiction films. They have an amazing film tradition there and great filmmakers. It was great preparation for what I’m doing now to work there.

What was your first instrument? What did you grow up playing?

JÓHANNSSON: My first instrument was the trombone. I studied trombone and piano basically.

There’s been a lot of interesting music that’s come out of Iceland in the last ten years or so, at least from the indie rock world. I’m wondering if you bring any Icelandic sensibility to the work you do and what would you characterize as an Icelandic sound?

JÓHANNSSON: I’m not sure what an Icelandic sound is. I don’t know. I come from there. I’m a product of Iceland and certainly of the Icelandic music scene. I was a big part of that, and it had a huge influence on me and all these groups like Björk, Sigur Rós, and Múm. All these bands are my peers and the people I grew up with and people I was playing with in small clubs in Reykjavik 15 years ago. So, I think there’s always an influence. I guess there’s something in common with some of those artists, but there are a lot of other artists from Iceland that you would maybe not define in the same way. I don’t know if you can group everything together like that.

I do my own records and my own artist albums, and then there’s the film music. When you write film music, you basically become a filmmaker. You’re serving the needs of the film and what the film requires. You’re basically a storyteller. You’re writing music to help tell the story. But also, what is very important and what I try to do is to keep my identity and my characteristics as a composer through that process and to navigate between those requirements of telling the story and serving the film and to also preserve and be true to my identity as a composer. That’s what I strive for.

The Theory of Everything is now in theaters.