Keanu Reeves wasn’t anyone’s first choice for Neo in the Wachowski Siblings’ The Matrix. Reports vary but everyone from Brad Pitt and Val Kilmer to Tom Cruise and Johnny Depp were reportedly in the running for the role of Neo. In hindsight, the choice of Reeves seems obvious. What so many people mistook as an idiot’s temperament in his youth, when he was starring in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, was an expertise in conveying inner peace, whether it’s intact or under attack. The Matrix presented a hero who had to come to vaguely spiritual inner realizations before he could become Computer Jesus, and Reeves has always had the uncanny ability to seem like he’s at once of this world and in touch with the metaphysical. The curtness of Neo’s demeanor on the page and Reeves’ oft-whispered vocal tone work melodiously together.

There had been hints of this kind of becalmed, wise bad-ass before – Little Buddha, for instance - but that’s not what had made him money recently. In 1994, he starred in Jan De Bont’s excellent Speed, but he played a hot shot. The assuredness that turned into wisdom and self-knowledge for The Matrix could also be utilized to convey brash cockiness. And yet here too, he was a refreshed and engaging version of a familiar hero, more focused on the job than family values or looking like a rebel. The cop he plays in Speed – Jack Traven – is an actual ideal officer and Speed hinged on the idea of an efficient, principled, and smart cop solving life-or-death problems at an urgent clip. The movie was not about how much of a manly man he was, as would have been required in a film starring Stallone, Van Damme, Willis, or, less so, Schwarzenegger. The focus was inventiveness, problem-solving, and thinking quickly, rather than being able to tell random colleagues where they can stick the proverbial it.

That’s the oft-forgotten greatness of Reeves’ abilities: he can often look both vacant and overwhelmed by complicated thought. This works especially to his benefit in Ron Howard’s Parenthood, where his character, Tod, is often belittled as an airhead who can’t see beyond his own nose, even when it comes to his impending fatherhood. And then, in one of the best scenes of one of Howard’s best movies, Reeves lowers the boom and alludes to a history of violent friction between himself and his own father. When Dianne Weist’s middle-aged divorcee talks about the need for a male influence on her teenage son, Tod responds with this:

“Well, it depends on the man. I had a man around. He used to wake me up every morning by flicking lit cigarettes at my head. He'd say, "Hey, asshole, get up and make me breakfast." You know, Mrs. Buckman, you need a license to buy a dog, or drive a car. Hell, you need a license to catch a fish! But they'll let any butt-reaming asshole be a father.”

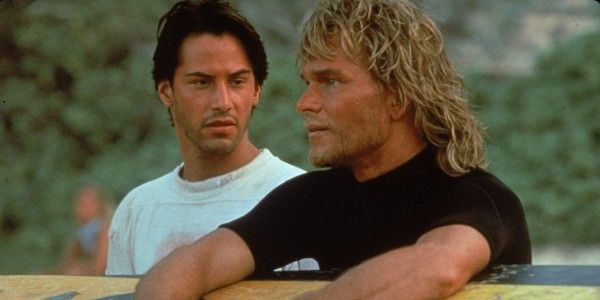

Reeves delivers this small speech without righteousness or anything like pride. Instead, he conveys exhaustion and experience, and the difference matters. As he has so often done, Reeves depicts an alternative vision of the masculine archetype, one that pushes beyond physical prowess, an overt sense of duty, and family values. Howard envisioned a new kind of makeshift family in Parenthood, wrecked by divorce, death, and hardships, and Reeves was a crucial part of depicting where this new kind of family and community came from. And it was important for Reeves to show this kind of male figure outside of his bemused and centered action heroes in Speed, The Matrix, and Kathryn Bigelow’s magnificent Point Break.

Up until The Matrix, one could always see the puckish, dimwitted metalhead from Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure beneath the guns, muscles, and police uniforms. There was always humor to their make-up and not the sarcastic, death-defying, know-it-all humor that gets snarled out by John McLane or Stallone’s myriad strongmen. After The Matrix, however, that became less true and his interest in the big hero characters seemed to noticeably shrink. This led him to one of his best performances, as the identity-scrambled undercover cop in Richard Linklater’s sublime adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly.

Unfortunately, this ambition also led him to attempt more villainous roles with severely diminished returns, whether in The Watcher or The Gift or Man of Tai Chi. As with his heroic roles, the underlying bemusement that typifies Reeves’ persona sneaks into the roles but in the case of villainy, he never quite makes the bent joy of sadism, control, or bigotry feel believable; his bad guys always come off as dull, empty, or confused. And in more feel-good projects like Hardball or Something’s Gotta Give, though his presence proves uniquely important to rendering them sufferable, he’s clearly on autopilot, drifting through the most familiar plot turns and narrative schemes on this blue planet. In movies of that ilk, there’s a consistent deficit of curiosity for the world or the characters, and Reeves often sustains his characters on curiosity and a need for discovery, both inside and out.

It’s fascination with an imagined world that initially made his 2014 comeback, John Wick, so effective and absurdly entertaining. The narrative centers on a quasi-mystical world of underground assassins and freelance operatives that work closely with crime lords, governments, and corporations to kill off those who need killing. The peculiar system of checks and balances at the hotel where Reeves’ titular, God-like hitman stays is just one of a few stylistic flourishes in the script that quickly separate the film from its familiar ilk. Wick is more morally and emotionally hardened than Reeves’ best characters, but the world is far more animated than those of Speed or The Matrix and the stakes are far more cartoonish. And though Wick isn’t much for jokes, he’s certainly not detached or above the scenarios he finds himself in.

Unlike so many other heroes, Wick is not spurred by a national or international crisis that threatens the free world, nor is he looking for vengeance against family members who have been raped or murdered. That’s not to say that the savage killing of a dog isn’t a grim prospect, but when considering the small mountain of dead bodies left in his wake, it feels irrevocably outlandish that this is where this violent reckoning originated.

It’s in the vaguely outrageous that Reeves has always worked best in. His work with Gus Van Sant on My Own Private Idaho and, to a far lesser extent, Even Cowgirls Get the Blues is marked by an outsider’s perspective that seems to underline his philosophical life on and off screen. He’s known for being a minimalist of sorts, and that seems to reflect his urge to convey his character’s inner world with clarity and curtness. He’s not known for playing characters that have a taste for flowery language, and he certainly seemed out of place with Shakespeare’s word in his mouth in Much Ado About Nothing. And yet, in something like John Wick, there’s eloquence and maybe even poetry in the selectiveness of his vocabulary, his unfettered way of speaking, and directness of what he chooses to say. At his best, his very presence brings balance to a dramatic situation, a feeling of reinforced peace even when bedlam rages all around him.