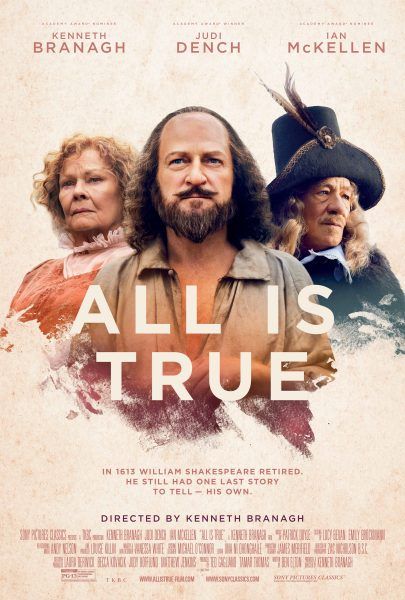

From director Kenneth Branagh and screenwriter Ben Elton, All Is True explores the last three years in the life of William Shakespeare (also played by Branagh), as he leaves London after a fire destroys the Globe Theatre and returns to his family in Stratford-upon-Avon. Once he’s back home, he tries to connect with his wife Anne (Judi Dench) and daughters Judith (Kathryn Wilder) and Susanna (Lydia Wilson), who are not particularly pleased that he’s back, especially with as haunted as he still is over the death of his son Hamnet, when he was only 11.

At the film’s Los Angeles press day, Collider got the opportunity to sit down and chat 1-on-1 with filmmaker/actor Kenneth Branagh about his longtime love of Shakespeare, what inspired All is True, how family drama is relatable in any era, shooting digitally for the first time, the collaborative experience of working with Judi Dench, figuring out how much to transform his appearance, and which Shakespeare adaptation he’d still like to do. He also talked about why the release date of Artemis Fowl got moved to 2020, how Death on the Nile will differ from Murder on the Orient Express, and whether he’s gotten the chance to see Avengers: Endgame yet.

Collider: Seeing as the work of Shakespeare has defined your career and life, in a sense, did you always think you might eventually actually get to play the man, himself? Did that seem like something that might be inevitable, at some point?

KENNETH BRANAGH: No. In fact, at some stages, I have been asked, but I’ve felt that there was maybe too much of an identification, or that it was a daft appropriation that I don’t deserve. This one just came out of a desire to do something very small. I wanted to do a small character piece. I wanted to just do a film about the internal lives of people, in a confined space and with some central issue for them, that an audience could really connect with, emotionally. I’m always fascinated by all things Shakespearean, and there was a very interesting book, called Shakespeare and His Circle, that came out. It’s a collection of monograms – quite small pieces, but a lot of them – about all of the people in Shakespeare’s life – each daughter, the son-in-law, and very pithy, human stuff. It made me think about what it would have been like, when he went back home after the Globe Theatre burnt down. I thought, “Maybe that’s where the chamber drama that I’m looking to work on exists. It exists in Stratford-upon-Avon.” I was reminded of all the people in his life, and thought about what they might be focusing on, at that time. I’d been in his play The Winter’s Tale, with Judi Dench, and the clear pre-occupation in that play, for the character of Leontes, who makes a ghastly mistake, is the loss of his son. That ache, and that sense of being haunted through the rest of the play by a dead child, was what Ben Elton and I talked about, when I ended up being asked to be in an episode of his sitcom, Upstart Crow, which is a very funny account of Shakespeare. We’d spent years talking about maybe doing something together, so I said, “Well, what about writing a drama about this subject that you’re now so enmeshed in, and starting somewhere around the death of Hamnet?”

It’s interesting how, if you took out the fact that it was Shakespeare, it’s so relatable to see a story about a guy who was so obsessed with his work that when he comes home, his family doesn’t really know how to relate to him and he doesn’t know how to relate to them. It doesn’t really matter what century that’s in, it’s easy to understand how that could happen.

BRANAGH: I agree, and I’m very glad to hear you say that. What I like about the movie, particularly, is that at the beginning of the film, there’s such a lot of silence between them all, and from a man who you might expect to be uttering great, deep, wise remarks and carrying some Jesus meets Buddha energy. Instead, out of these long silences, he says, “I thought I’d make a garden.” It seems so simple and absurd. I wanted to make a movie about silences, it just happened to be concerning a man who was a master of words and from whom you might expect much the opposite of silence. I enjoyed that. I felt like that was the beginning of trying to get behind the man.

This was the first film that you shot digitally.

BRANAGH: That’s correct, yeah.

How was that, as an experience, and is that something you think you’ll continue to do, or will you still also use film?

BRANAGH: All things being equal, when we do Death on the Nile, I hope that I’ll shoot on 65mm film again. But here, we knew that we wanted long takes, so changing film magazines was a factor, in terms of savings and time. When I suggested, strongly, that we should be shooting the nighttime stuff by candlelight and only candlelight, Zac Nicholson, our very excellent cinematographer, said, “I think, then, that digital is going to help you. It’s going to help you in post. It’s going to help you, in the way that you can grade the movie. And if you want to do long takes, and you’re going to sit down and do a seven-minute scene with Ian McKellen and not cut in between, then you’ll probably want to be on a digital card that will give you half an hour, and not 10 minutes.” It allowed us to be nimble and fleet of foot, and it was photographically apt for the lighting conditions that we were presenting. We were shooting in natural daylight during the day, so our visual style was less film friendly than previous things. I’d worked with digital before, as an actor, and I really enjoyed watching Anthony Dod Mantle, who is a terrific filmmaker and who was DP on Slumdog Millionaire, for which he won the Oscar. He was the DP for the first episodes of Wallander, and I loved his abstract style and what he did, by way of pushing light levels with the digital format. So, I was happy to experiment in it. This is the only feature of mine that I haven’t shot on film, out of those 16 or 17 movies. But I’ll be back to film, I hope. We shot Artemis Fowl, which I did for Disney last year, on film.

Do you know why the release date for Artemis Fowl got pushed, from August 2019 to May 2020?

BRANAGH: It got moved in the massive reorganization. I don’t know how many dates got moved, but most of the catalog got moved. Essentially, now that Disney has all of these companies, they’re spreading it out, so that they don’t cannibalize each other. I’m pleased that ours goes to the late spring. I’m happy about that. These things happen.

Is that something that you just don’t have any control over?

BRANAGH: Not in a million years.

How was the experience of making All is True with Judi Dench? Is it easy and effortless to work with her?

BRANAGH: You know, it was effortless because she’s not cozy and smug about the work. She’s always very rigorous about that, so she would never allow, in our case, a good, happy, collaborative spirit to be a way of just making life simpler or easier. She is still always in rigorous examination of the part and what it needs. She doesn’t like any shortcuts. She enjoys the trust and the shorthand, but she doesn’t want a shortcut to the truth of the character. If she has a problem, she says it, and if she sees something that she thinks I’m doing wrong, either as actor or director, she will quietly and sensitively point it out to me. So, in that sense, she’s a very precious person to work with because she does all that, but also turns up on time, is a professional, and is the very best kind of worrier about her work.

How often did it happen, that she pointed something out?

BRANAGH: She walked on one time and said, “This seems rather theatrical.” I said, “What do you mean?” She said, “Well, it’s just where your camera is.” So, I talked her through it and she said, “Oh, I see what you mean. I hadn’t understood that.” We had a good conversation about it. And also, I remember a scene where she started laughing because I had paraphrased the piece of Shakespeare I was quoting, which was from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and of course that gave her enormous pleasure, that I had messed up on camera. At the end of it, I said, “Well, you probably know the rest of this, don’t you?,” and she finished the scene for me, and then burst out laughing. That ended up in the movie. We kept it in because it was definitely a moment of connection between those two people, that you would say is a good by-product of our working relationship. I’m very happy to have my mistakes pointed out by Judi Dench.

Clearly, you don’t exactly look like you, in this film.

BRANAGH: Yes.

How did that whole process work? Did you go through a process of figuring out how much you wanted to change your appearance?

BRANAGH: Yeah, there was a big conversation to be had, at the beginning. I wanted to try to give the world the familiar image of William Shakespeare, with his high collar, his high domed forehead, his beard, and the larger nose. It’s everything that’s in the Chandos portrait of him that John Taylor painted, that’s in the National Portrait Gallery in London, and that’s been reproduced on a million tea towels, key rings, and things around the world. What that portrait also has is tremendously warm, provocative, funny eyes. The warmth in the eyes is really, really striking. And so, ultimately, I thought that it was helpful to get rid of me. It was helpful to get rid of me and try to really set up what the film’s trying to do, which is that the world thinks this thing about Shakespeare – that he’s a genius who’s removed, inhuman, permanently wise, and observes and writes about the human condition, but there’s no evidence to suggest that he lived in the way that we all do. In fact, I wanted to say that very same person does, in fact, engage with life like we do. He has friends, wants, hopes and dreams, and his children are unimpressed by him. People in his life die, and he suffers losses. I wanted to introduce people to him.

When I was in junior high and high school, reading Shakespeare was something that I struggled with being able to connect to. It wasn’t until I started seeing your Shakespeare films that, for whatever reason, I gained a love of his work that I didn’t have from just reading it. So, I’m forever grateful for that.

BRANAGH: Thank you.

Is there a Shakespeare adaptation that you still would like to do? Is there one on the horizon that you haven’t gotten to do yet?

BRANAGH: I quite like the idea of possibly making a film of The Comedy of Errors because it was the first play that academics would agree established a mature Shakespeare. He was writing better, but still had the same preoccupation, with twins that get separated and a father with an aching loss for the missing child, or children. It has broad humor and a brilliant command of comic technique. So, I’d love to do another Shakespeare, like Much Ado About Nothing, that really moves people and makes them laugh.

How would you say Death on the Nile will differ from Murder on the Orient Express?

BRANAGH: The Agatha Christie Estate has allowed Michael Green, who has done the screenplay again, to add some characters and to change some plot. They feel, and I think Agatha Christie felt, that it’s a better book. She said that in her introduction, and it captures a flavor of reality that was very personal to her. There’s a love triangle, at the center of it, but it’s mirrored in other relationships in the story. She definitely had a tremendous bruising, in her own life, relative to marriage and love, so she had immense personal sympathy and investment, in not just the love that runs through it, but also the lust that runs through it. It’s a very sexy book. It certainly unleashes a series of primal appetites, for sex and death.

And it has a pretty great cast, with Gal Gadot, Armie Hammer and Letitia Wright.

BRANAGH: Yes, it’s all shaping up to be very exciting. I’m looking forward to it, and looking forward to getting my mustache back on.

As somebody who has played in the Marvel Universe a bit, have you gotten to see Avengers: Endgame?

BRANAGH: I haven’t seen Endgame. I can’t wait to see it, and to enjoy it like a wonderful meal. But I literally tried six different cinemas, on the opening weekend, and couldn’t get in. I said to my missus, “If that’s what’s happening where we live, then this movie is going to take more money this weekend than anything in the history of anything.” And that, indeed, was the case.

How does it feel to have had a hand in that, and then get to see what it went on to become?

BRANAGH: It’s a slight out-of-body experience, except that I still feel like a member of the family. I hear from the boys and girls, at various times. They rang me up, a year ago, and said, “Would you come and be this voice at the beginning of Infinity War?” And so, it feels like it’s an ongoing relationship. I feel like I’m a part of the family.

Is it fun to have that balance between the smaller, more intimate films versus the big ones?

BRANAGH: It is. Lots of people said, at the time, and maybe it was an obvious connection, that there’s a Shakespearean quality in Thor. I think there’s something to that. That dynastic struggle with Odin and the family was something that I didn’t have any fears about trying to present, at a high volume of emotion, knowing that it could be something that you could riff lots of humor off of, as long as you centrally believed that Loki and Odin and Thor all cared about it, at that point.

Family drama is always relatable.

BRANAGH: Yes, exactly. We’ve all been there. But often, without capes or the ability to fly.

All is True is now playing in theaters.