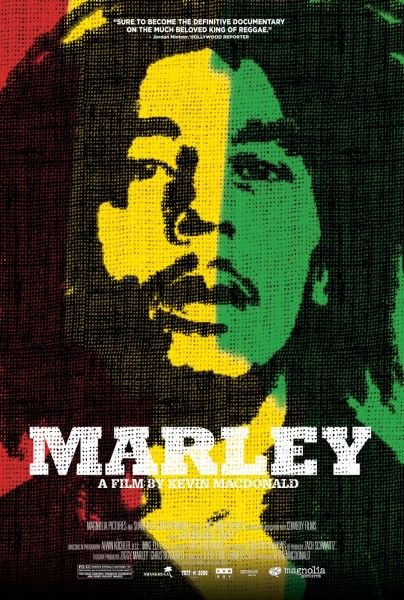

For nearly half a century, Bob Marley’s music and his message have resonated powerfully on a global level that remains unparalleled. Academy Award-winning director Kevin Macdonald’s new documentary, Marley, is the definitive life story of the musician, revolutionary, and legend from his early days to his rise to international superstardom. Made with the support of the Marley family, Marley features rare footage, incredible performances and revealing interviews with the people that knew him best. The film also gives the audience a more emotional connection to Marley’s life as a man. Magnolia Pictures will release Marley theatrically and on VOD on Friday, April 20th.

At the press day for Marley, we sat down with Macdonald for an exclusive interview. We talked about what inspired him to make a documentary about the enigmatic Bob Marley who transcended music to become a cultural, political and social icon for change. He told us about what he hoped to achieve by making this film, how he set out to reveal a human side of a towering figure in musical history, and why he thinks Marley still speaks to people around the world today as powerfully as he did when he was alive and more profoundly than any other rock artist or popular music artist. Macdonald also discussed his upcoming projects including How I Live Now with Saoirse Ronan, Bobby Fischer Goes to War and Black Sea.

Question: The Marley project goes back at least 6 years, and at one point, Martin Scorsese and Jonathem Demme were both interested. How did you first become involved?

MACDONALD: I guess my involvement with Marley started a little before that, a couple of years before that. It was about seven or eight years ago when it was going to be Bob’s 60th birthday or would have been his 60th birthday. I started talking to Chris Blackwell, who’s the founder of Island Records and features in the documentary, about maybe doing a film which would take some Rastas from Jamaica to Ethiopia, to the culture that was being planned there, and I thought this would be an interesting, anthropological film, tangentially to do with Bob, obviously. But that film didn’t happen, but I got to know him. And then, a couple of years ago, he mentioned to Steve Bing, who’s the producer of the film, who had already spoken to these other directors and gone someway down the path with a couple of directors, “Oh, I know that Kevin is interested in Bob Marley. We spoke about it awhile ago and maybe you should talk to him.” And that’s what happened. So, having not made any film about Bob seven or eight years ago, I made one now. It was kind of serendipitous.

There have been a lot of concert films and biographies that have attempted to explore his story over the years since his death. What intrigued you about Marley and what did you hope to achieve by making this film?

MACDONALD: I felt that there wasn’t really anything that was very good that had been done about him, certainly in terms of documentaries. I think the last major documentary was 1996, 1997, something like that. I felt like they didn’t really capture the man, and you were left wondering by the books as well. I still don’t feel like I know what he was really like. I think there were a lot of inconsistencies and contradictions in the different biographies. It felt to me like the impulse for me when you’re confronted by an icon or a larger than life character is to say “Oh, what’s behind the iconography? What’s behind the legend? Who’s the man? What’s the man like?” And so, that’s really what interested me in this. I wanted to make very simply a biopic in the true sense of making a biography of this man and see if I could find out who was the human being and make a very hopefully human portrait of him, rather than a kind of air-brushed celebrity portrait.

Did you have a passion for and interest in his life as a person and as a musician before you started the film?

MACDONALD: I loved his music, but I think everyone loves his music, so that’s not very good qualification. (laughs) Uprising was one of the first three or four albums I ever bought in 1980 when I was 13, and that had a strong impact on me. But, after that, I’d bought other stuff as well. I wasn’t the kind of rabid collector. I didn’t track down every bootleg of him. I liked his music, but I think it was more just the feeling that wherever I went in the world I would see images of Bob Marley. Whether you were going to Africa or you’re going to India or you go to Italy, you’re confronted by murals of Bob Marley and his lyrics spray painted everywhere and his music being covered by different musicians and bands. In particular, when I made the film The Last King of Scotland, I was in Kampala in Uganda and was amazed by how much Bob was present for a lot of people, how his image and his music were so potent. I began to think that that’s unique. Nobody else has done a musician who’s like that, who’s revered in the way that he’s revered, who’s treated almost like a philosopher or a prophet or a poet. He’s not just liked because the music is good, and that makes him special. That makes him really an important cultural figure because he’s had this long running influence and it’s around the world. It’s not just in the West. If anything, it’s more so in the developing world. He’s the only third world superstar. He’s one of the great icons of music if you think about Elvis, the Beatles, the Stones. None of them are from the third world. None of them grew up in the kind of poverty that he grew up in.

You interviewed a lot of key people in Bob’s life that influenced him as a person and as a musician, and you were very successful at putting his family and friends at ease. What was that process and experience like?

MACDONALD: The whole film felt a very organic way. I didn’t know what story I was really going to tell. I didn’t go in with a preconception as to what the story would be or an angle in particular. I said to Ziggy Marley, Bob’s eldest son, who was involved in setting up the film, “I’m just going to try and interview everybody I can who knew your Dad.” And that’s what I did, even though not everybody knew him intimately. I interviewed about 90 people and I think about 50 people or so are in the film, so a lot of people. And then, a kind of mosaic picture of him built up through all the recollections of all these different people, and so by the end of it, I did feel like “Oh, I kind of can see what he was like.” One of the things about Bob is that he didn’t give more than three or four filmed interviews in his whole career, and when he did give interviews, he obviously didn’t like it very much. He was uncomfortable or he toyed with the interviewer and didn’t answer their questions. So, there’s a level of mystery about him because he never spoke for himself. He spoke through his music, but not through any other means. It may add something to that mystique that that creates [which] is part of the attraction of Bob. So, although I feel like I understand him in a way now, I don’t feel like I know him because I think he retains his mystique.

How was it gaining the cooperation of the Marley family and did you encounter any reluctance?

MACDONALD: When I got involved, Steve Bing, the producer, had already done a deal with the family and got them involved. He did a deal with Universal Music who had the music and got the family involved, and I think the family wanted to be involved because there were eleven children that Bob had and the eldest were 12 and 14 when he died, and so they were very young. They didn’t know their father. I think part of the motivation was they literally wanted to know about their father and have all the people who knew him talk about him. And so, they were very generous with me. They tried to have no control over the movie. They let me ask any questions I wanted, and there were obviously some quite uncomfortable things that were raised in the film. They were totally honest and very open. That’s a great testament to them. But I think it’s as much about them wanting to know their father and that’s certainly what they’ve said to me after seeing the film. The various children who I’ve spoken to have said, “I’ve learned so much about my father. I didn’t know this stuff.” I sat the other day next to Bob’s grandson who’s called Nestor Marley, one of his grandsons. He watched the movie and I was sitting next to him and he was crying. He was learning all this stuff and suddenly it was affecting him.

This is a very personal film that’s both a biopic and a musical journey. How did you go about weaving the two together?

MACDONALD: In order to understand him, you need to be educated about quite a few things because it’s quite alien to what’s going on with a lot of us. What is Rasta? How is it possible that people worship a dead Ethiopian emperor? What was the political scene there? Why did someone try to shoot him? You need to explain a lot of background stuff in order to make the music accessible and to really fully understand him and the music. That was the big difficult balance for me – how to balance the life, the music and the world that he lived in and explaining that world.

Your film captures many facets of Marley’s life and artistry. What was the biggest discovery you made about him in the process of making this film?

MACDONALD: Well I think there were a lot of things that I discovered, a lot of things that even his own family didn’t know about. Ziggy was just saying to me this morning – we were doing an interview together and somebody said to him, “When your mother talks about all the affairs that your father had and how she dealt with that, had she spoken to you about that before? Did you know that was how she felt?” and he said “No. That was the first time I’d heard her say that.” So, those sorts of things were not just new to me, but they were new to everybody. But there’s lots of stuff. I think the importance of Bob being mixed race to the story and to who he was and his search for identity really, and in some ways his whole life, is a quest for finding out who he was and where he belonged in the world. That started with the fact that he was the product of a brief relationship between a white guy and a young black girl and he never really knew his father. But he was not accepted either by the black Jamaicans or the white Jamaicans. He was an outcast from both. And that lack of acceptance, I think, made him strong, made him really tough because he had to survive on his own. But, it also in some way gave him the motivation to succeed, to say I’m going to prove to you guys that I’m somebody. I can do it.

What do you think makes him such an iconic figure? Why has his popularity and influence continued to grow 30 years after his passing?

MACDONALD: There’s complicated answers and simple answers. It also depends on what part of the world. As I was saying, in the developing world, it’s quite different. I think he speaks to people who feel themselves to be downtrodden and pressed and with a message of hope, and because you can tell from his voice that here’s somebody who’s singing about these things who actually has experienced them. There’s an interesting quote by Lee “Scratch” Perry, the famous producer. He’s a crazy guy but he’s fantastic as well. In the film, I said to him “Why do people remember Bob’s music so much?” and he said “It’s the message that he has, but it’s also the way that he says it.” I think that’s very simple but very astute. It’s Bob’s voice and this feeling of experience and wisdom that comes in which has this timbre. I think in the West – I use the term ‘the West’ to mean America and Europe – he’s come to represent simultaneously an anti-establishmentism and rebelliousness, and he gives people, I think, a feeling that there’s an alternative. I think that’s always very attractive, that there’s an alternative to the mainstream establishment life that you’re leading. It’s also positive music, a lot of it. Most of it is positive music. It’s music that makes you happy. It makes you feel positive about life. That’s pretty potent. To sing positively and not to sound phony is very hard, and he does that. I think there’s also just that he’s the patron saint of pot smokers. People like pot and therefore they like him. There’s an element of him that he’s just the man on the T-shirt and the man on the poster. It’s just this iconic Che Guevara that he’s become. But, behind that, there’s also something. He is somebody who is really saying something.

What is it about Marley’s background, his music and his message that resonates so powerfully and gives him such universal appeal?

MACDONALD: I think it’s the fact he knew poverty. He was the only third world superstar. I think that’s the key to it.

Were there any unusual challenges you encountered while making this documentary?

MACDONALD: Well, most of the challenges were getting people to talk, because as I said, my aim was to get everybody who knew him. I didn’t want to get people who were celebrities to say “I know him from ... He’s so great.” Or any of that kind of awe stuff that you get in these sort of documentaries – but just the ordinary people who knew him who could talk about his character and his life. So, those people in Jamaica, in particular, there’s a lot of poverty there. People want money to talk about things or they’re resentful. They feel they were ripped off in the past and they should have been compensated for something in the days of Bob or after Bob. So, it’s a lot of negotiating with people and explaining why it was important to talk. And in the end, we did get everybody but it took over a year. Buddy Wailer, I think, was nine months from when we first contacted him until he agreed to finally do the interview. It was a lot of perseverance. Also, the other thing is just getting hold of photographs and archive footage. The amazing thing about Bob Marley is that there is no moving footage of him at all for the first ten or eleven years of his career. From 1962 to 1973, there’s nothing, not a single frame. After that, there’s some but it’s not huge amounts, not compared to some of the other great music figures. So that’s a real challenge. How do you make a film when you’ve got little amount of footage? And then, even the footage there was, again you have to negotiate with people who own this photograph, that photograph, or this little bit of film. There’s a lot of politics involved in making this film.

How did you decide what was relevant and should be included in the film and what was not?

MACDONALD: I think it’s mostly about the musical performance and it’s about what affects you, what is beautiful, what is a lovely performance, what’s nicely shot. There isn’t that much of it so if you find something that’s good, you’re going to use it. We were also lucky to find … we had a great archive researcher and she found some bits of footage that had never been seen before of Bob performing and in Trenchtown that had never seen before and of the Rasta community. Also, we found versions of songs like No Woman, No Cry that never had been heard before so there’s an excitement in that as well as just in unearthing new things.

How has the family reacted now that they’ve seen the finished film?

MACDONALD: They’ve been really, really thrilled, I think. They’re really positive about it and they’re supporting it. The great thing was that they saw it and they were all moved. At the first screening with Ziggy, he was crying. I think what they like about it is that it’s an emotional film and that it is warts and all. It’s not burnishing the icon. As I said before, they feel like they’ve learned stuff about their father that they didn’t know. I think it will also introduce a whole new generation of people to Bob. That’s what they hope. And then, maybe even not introduce because everyone knows the music. No matter how old you are, people hear the music. But maybe it makes you listen to it in a fresh way. You hear it in a supermarket. You hear it in a restaurant. But you don’t really listen to it anymore because it’s background noise and you’re familiar with it. But hopefully, after seeing this film, you’ll actually listen and hear it in a different context.

If Marley were alive to see this film, what do you think his reaction would be?

MACDONALD: I would hope that he would like it, because I would hope that he would recognize that it’s done with integrity. I think he was a man of huge integrity and I think he wouldn’t want to be portrayed in a way that was sort of puffed up and dishonest. That’s what I think. But also, he didn’t have much time for journalists or anyone trying to explain him. He didn’t like that, I think. So, who knows?

Can you talk about your upcoming projects?

MACDONALD: I’m doing a film called How I Live Now which is a very dark teen romance set in a kind of alternative version of the present. You think it’s the present. You think it’s now. It’s about an American girl who goes to stay with her cousins for the summer. She’s a troubled girl. Her mother’s dead and she goes to stay with her cousins and she falls in love with her cousin. And then, all sorts of weird and strange things begin to happen. It stars Saoirse Ronan who’s a lovely young Irish actress who was in Atonement, Hanna and Lovely Bones and things like that. Yes, that’s what I’m doing next.

What about Bobby Fischer Goes to War? Is that still in development?

MACDONALD: That’s on my list but it’s not been a living project for a while.

Is Black Sea one of your projects too?

MACDONALD: Yes, that’s a submarine film. I will hopefully do that next year.

Marley will open in limited release across the U.S. on April 20.