When David Bowie passed away earlier this year, following the release of his brilliant last record, Blackstar, no one seemed to have the same memory of him. On my Facebook feed, there was rarely a repeat in the pictures posted to mourn the world’s tremendous loss, and when I ask people what they remember about him, its almost always different. My mom remembers him in Zoolander; my good friend e-mailed me the scenes from Mauvais Sang and Frances Ha where the characters run down the street to “Modern Love.”

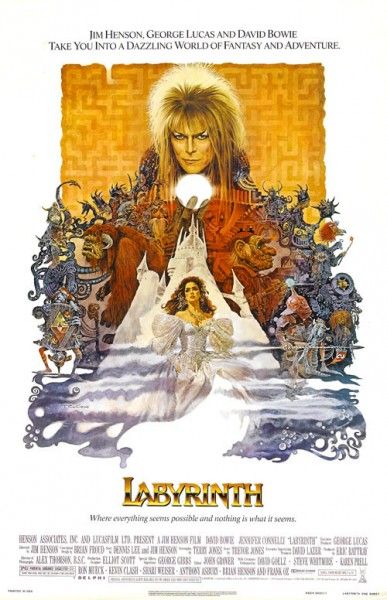

If there was one tendency, however, it was toward Labyrinth, Jim Henson’s delightful, fantastical adventure, in which Bowie played Jareth the Goblin King. I can’t say this is particularly surprising in terms of nostalgia. As much as my friends may have worshipped at the altar of Nicholas Roeg’s uncanny The Man Who Fell to Earth, in which Bowie played an androgynous alien, there’s something about pairing Bowie with a genius designer and craftsman like Henson that is distinctly fruitful. It’s hard to imagine anyone being at home in Henson’s world of endless discovery, but Bowie’s bold theatrical take on the character matched the delirious and spasmodic actions of the puppet Goblins that surround him. And though the dubbing is inevitably not so good, his songs speak to the heart of the film’s thoughtful consideration of the power of imagination, its lighter side as much as its darker.

When Bowie sings “The Magic Dance” about a half hour into the film or so, its to both entertain and gather his minions but also to make the baby he kidnapped, Toby, feel at home with his new guardians. It was during a frustrated tirade back in her suburban hope that Sarah (Jennifer Connelly) called down the power of the Goblin King to get rid of Toby, her brother, who was constantly being made Sarah’s charge by her stepmother. The grudge between Sarah and her stepmother spurs the anti-authoritarian mood of Labyrinth, and one could view the adventure that Sarah takes on as proof of not only her maturity and responsibility but also her familial instincts, as both a sister and a proxy mother.

That’s the undercurrent to all of this, but there’s more than enough on the surface of Henson’s film. Sarah essentially creates the Labyrinth world via the stuffed animals, dolls, and bookends, and in one scene its alluded to that she’s authoring an account of the happenings in the Goblin King’s realm. To escape the banality and unexpected pressures of the real world, she creates fantasy worlds, not unlike Henson, and there’s a constant feeling that the director and creature designer, as well as writer Terry Jones, are plumbing their own feelings about a life made from conjuring up hairy beasts, friendly serpents, and gawking mutant birds, amongst other things. Sarah’s task is to find the end to the labyrinth, but there’s more time spent interacting with wall-people and the Bog of Eternal Stench then there is over-explaining the world, her motives, or the mythology of the place, which puts it in stark contrast with 94% of modern fantasy movies.

Indeed, Jones, a founding member of Monty Python, cuts out a great deal of the exposition and climactic build-up in the script to allow for the characters to explore the space and world that has been so lovingly built in Labyrinth. When Sarah must cross the Bog with Hoggle, voiced by Jim’s son Brian Henson, there’s an extended comic riff between Sir Didymus, the knightly fox, and Ludo, a friendly, magical beast who can summon rocks, and the power later comes in handy when a chasm blocks their way. There are fleeting reminders that there is a clock on this whole adventure, before Goblin King takes Toby and turns him into a baby goblin, but they never take away from Henson taking his time taking in the wonder of how these puppets move, react, look, and sound. Just seeing Ludo walk so seamlessly across the rocks feels like a rare kind of visual treat.

That most of these extraordinary beings and places are made by physical effects, with the notable exceptions of those wise-ass knockers and the computer-generated owl over the opening credits. There are other instances that escape my sight, I’m sure, but one thing that defiantly comes through is the sense of craft that went into the world. Few films wear the work of their technical crew so openly in the final product, for fear that viewers will not feel fully immersed in the kingdom they’ve created, but Labyrinth never feels disconnected from the story being told. The film demands a modicum of imagination from the audience to buy into the minor tenants of the narrative, and in return, the entire movie radiates an indisputable warmth that comes from studied, unique, and intimate design and physical work, which can be seen on Hoggle’s face as much as in the extraordinary “Helping Hands” sequence.

As Sarah learns, her imagination can have great power, to the point that she can make herself dangerously obsessed with continuing to build and expand the land she’s made. The film shows all sides of the imaginative adolescent mind, from the adorable and easily lovable Ludo to the sheer madness exhibited by the creatures known as the Fireys, who take their heads off and toss them around. Beyond that, Jareth comes to represent a kind of repressed vision of sexual desire, but also reflects a societal need for Sarah to cater to a man rather than becoming more independent. When Sarah takes a bite of a cursed peach, she ends up back in her room, being told to hold onto all her childhood memorabilia, memories, and feelings; she’s also shown off as something like Jareth’s bride and prized possession at the weirdest costume ball this side of Batman Returns.

There’s even a sense that Jareth represents some stud that might try to sweep Connelly’s Sarah off her feet, get her pregnant, and divert her from her passions and brainy abilities. And that’s what makes climactic turn of the film, when Sarah simply opts out of Jareth’s deal, an act that shakes her back to reality right as her situation in that M.C. Escher room was growing a bit grim, so radical. In essence, Henson and Jones underline a rote but undeniable philosophical concept – it’s not the destination, it’s the journey - by pulling the rug out from underneath the entire dramatic structure of the movie. 30 years later, I still watch that moment in awe, and grin like the biggest idiot when Sarah is reunited with Hoggle, Sir Didymus, and her other friends on her bed.

Bowie’s hand in the success of this should not be undersold. As a character, Jareth seems to be having infinitely more fun than most film villains do, and Jones is careful not to stress some sadistic side or a rigid belief in evil as a kind of religious duty. He sees his deal with Sarah as a kind of dalliance, and dancing around with puppets and lip-syncing his songs for the soundtrack, he conveys an irregular, unhinged joy in life that is often robbed of all malevolent beings to accentuate their general hatefulness. And because Bowie plays him, Jareth is also a seductive presence, which emphasizes just how easy it is to fall for such games. Despite some very dark imagery and subject matter, there’s a crucial lightness in tone when it comes to Labyrinth that’s not easy to express but feels effortless under Henson. This would be his last film as a director, following The Dark Crystal and The Great Muppet Caper, and more than either of those films, Labyrinth relentlessly echoes his most intoxicating thoughts about working as a visual artist and about the overwhelming glee with which he believed challenges, adventures, and life itself should be greeted.