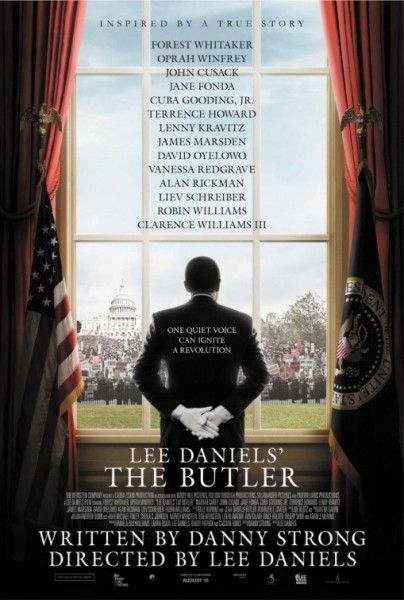

Lee Daniels has no place for subtlety in his movies, and that's not necessarily a bad thing. It can translate to earnestness. It can also translate to bugfuck insanity that makes the audience uncomfortable in a way that feels incredibly exploitative. Lee Daniels' The Butler (formerly titled "The Butler" but forced to change due to a petty dispute between The Weinstein Company and Warner Bros.) disconcertingly hints towards the latter before thankfully settling into the former. Daniels takes his passion towards race relations, and brings a fresh perspective to the civil rights movement by providing not only the unique viewpoint of a White House butler, but also from the butler's son, who was fighting on the ground while those in government wrestled with the increased racial tension of the 1960s and 70s. The film could stand to lose 15 minutes of unnecessary material regarding Oprah Winfrey's character, but it's a solid story of a father and son pulled apart by the tides of history.

After an opening shot of an old Cecil Gaines sitting in the White House foyer, The Butler spends its first five minutes having a young Cecil happily taking a photo with his family on a plantation in Macon, GA in 1926 before the cruel owner (Alex Pettyfer) goes off to rape Cecil's mother (Mariah Carey) and then shoot his father (David Banner) in the head. The owner's mother (Vanessa Redgrave) comforts the young Cecil by telling him she'll turn the boy into a great "house n*gger". Again, this is in the first five minutes, and it sets up a melodrama that thankfully never arrives. Instead, once an adult Cecil (Forest Whitaker) gets a job as a butler at the White House thanks to his domestic expertise, the film turns its focus on his observation of how Presidents Eisenhower (Robin Williams), Kennedy (James Marsden), Johnson (Liev Schreiber), and Nixon (John Cusack) dealt with the civil rights movement. This observation is contrasted with the movements of Cecil's son, Louis (David Oyelowo), who is a member of the Freedom Riders and a great source of consternation for his father and mother (Winfrey).

The 1960s were a very important time, but the impact of their importance has been diminished both by the distance of time and by how much they're removed from the standard talking points of the historiography. We all learned (or at least I hope we all learned) the history of the civil rights movement, but it's always boiled down to marches, sit-ins, Martin Luther King Jr., and the evils of the KKK and other forces of intolerance. The Butler takes a different perspective both within the standard narrative of the civil rights movement and from African-Americans not actively involved with the protests.

Cecil's observations of the presidents dealing with the civil rights movement are the hook, but it's also the background. Instead, the presidents always serve as a reminder of Cecil's estrangement from his son. To Cecil, service means subservience, and that means survival. It means the opportunities he's been able to provide his children, and that other African-Americans from Cecil's generation were able to give their children. The unforeseen consequence is that these young people, shaped by a different time and circumstances, now feel the freedom to push for more freedom, which is at odds with the cautious values of their parents.

This generational divide is illuminating for several reasons. First, it's a reminder that not every single black person in America was an active part of the civil rights movement. It deeply frightened some of them, especially those who felt a parental obligation before a societal obligation. Cecil and his wife Gloria aren't against the civil rights movement, but it's not their primary concern. Louis' safety is, and also how his actions might reflect badly upon his father. The importance of the civil rights movement isn't in dispute, but it reaches beyond the familiar history. The young black people fighting for civil rights didn't come from nowhere. They came from families, and that family dynamic provides an added dimension to how the civil rights movement is depicted in mainstream movies.

The dynamic is also helped by how quietly Whitaker and Oyelowo play their roles. For a movie beset with Daniels' complete inability for subtlety, his lead actors provide the quiet grace to keep the picture grounded. This isn't a picture about heated arguments or grand speeches. Cecil has learned to keep his emotions in check, and despite his apolitical views clashing against his politically-driven son, Louis maintains that quiet as well. Because of their race and their goals, they don't have the luxury of anger. This demeanor isn't only necessary to the story, but it helps dissolve the melodrama that threatened to overtake the picture at the outset. Whitaker and especially Oyelowo are tremendous as they convey so much while rarely resorting to histrionics.

When focusing on Cecil and Louis, the movie is at its best and clearly conveys its themes. Outside of the father and son, The Butler can get easily side-trekked and distracting. The most notorious example is trying to beef up Gloria's plotline by focusing on her alcoholism and affair with a neighbor played by Terrence Howard. Giving Winfrey so much screen time feels like more of a "Thank You" for her support of Precious than anything that contributes to The Butler's overall story. Cecil's strained marriage could have been conveyed easily without Howard's scenes. As for the rest of the cast, some perform admirably like Cecil's fellow servants (played by Cuba Gooding Jr. and Lenny Kravitz) and on the other end of the spectrum you have John Cusack sporting a fake nose and trying to do a Nixon impression.

These kinds of distractions come along because Daniels can't help himself, and it's almost endearing in the case of The Butler because at least it's coming from a place where he's trying to find a new way to explore a familiar period in American history. There's a responsibility, and Daniels tries to honor that responsibility by letting you know how everyone is supposed to feel and to have characters spell out the themes. It's frustrating, but not infuriating because a heavy handed message is somewhat more bearable when the message is at least somewhat original. Lee Daniels' The Butler isn't just about "how the other half lived". It's about how the other half could be as divided as the nation, and while the ending serves to undermine that notion somewhat, it's also the only ending the film could reasonably come to with Daniels' as the messenger.

Rating: B-