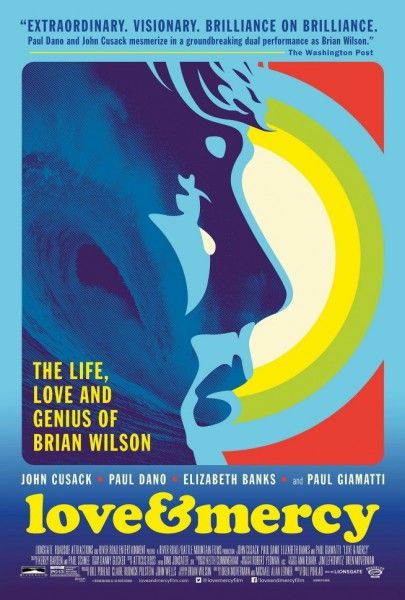

I’ve seen a lot of biopics. Most are forgettable. Many feel like a Lifetime movie that somehow got a theatrical release. Director Bill Pohlad’s Brian Wilson biopic Love & Mercy is not one of those films. Written by Oren Moverman, the film takes a non-traditional approach to telling the Beach Boys member's life by splitting the story between Wilson in his 20s (Paul Dano) and Wilson in his 40s (John Cusack), and it doesn’t shy away from showing the dark side of Wilson’s mental illness that almost consumed him. Loaded with a cast giving it their all, a great script, and superb direction, Love & Mercy is a fantastic film that deserves your time and money. The movie also stars Elizabeth Banks, Paul Giamatti, Jake Abel, Bill Camp, and features a tremendous soundtrack. For more on the film, read Adam’s review or watch the trailer.

The other day I sat down with Oren Moverman. He talked about making the story cinematic, bringing the script down from 170 to 120 pages, balancing fact and fiction, what surprised him while researching the project, deleted scenes, his next movie, Time Out of Mind, his Kurt Cobain script This is Gonna Suck, and a lot more.

Collider: I’ll start by saying I loved Love & Mercy and the thing about it is that it’s very cinematic and it feels like a movie; and sometimes these can be Lifetime-esque films and this is not that.

OREN MOVERMAN: Or an ABC miniseries about Beach Boys, which we had a few years ago.

100%, so talk a little bit about what was the key for you in making it cinematic.

MOVERMAN: Well that’s kind of the job, it’s sort of how you define it. When Bill [Pohlad] got in touch with me and we started talking about it - Bill is such a cinema guy, having worked with Terrence Malick, Ang Lee, Robert Altman; he’s so attuned to cinema that you sort of have the first initial conversation about how do we find the cinematic equivalent that would work with the music, translate the music to cinema, but also translate the life into a narrative that is cinematic. We were very aware of the big-screen, of the theatrical experience. What we wanted to do was sort of an immersive film that lets you experience certain elements, because you can’t tell the whole story it’s too much of a story. Actually, the first draft that I wrote was almost 170 pages and I felt it was too short. I remember sending an email to Bill saying, ‘Here’s the first draft attached, I feel it’s too short.’ It had 100 songs, 170 pages and I just felt like I didn’t do enough to tell the story. So we had a long conversation where he basically said, ‘Well you did 150%, we need you to do 100%.’ And I said, ‘That’s really hard,’ and that’s when we started working together on a daily basis basically and when I realized that he’s actually the director of the movie not just the producer, before he even realized it.

We wanted to make a cinematic experience that translates the music and the life, but gives you almost a communal experience in sitting with people in an audience in the theater and going through that insanity –literal and metaphorical– that was his life. He was always aware of the big-screen, and how you experience movies, and what you can do with sound, what you can do with translating these kind of amazing, inexplicable compositions that he was hearing in his head. How do you tell a story about process? Because it’s not just about a guy who did this, this, and that, and then this is what happened; it’s also about a guy who sat in a studio and created these symphonies.

What did you lose in the editing process, bringing it down to say 120 pages or whatever you did? What was the 50% that got pulled out?

MOVERMAN: First and foremost it was the ‘70s, because originally when I met with Bill and we started talking about it we said, “Let’s do Brian [Wilson] in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s,” and we actually gave it a clear distinction it was Brian past is the ‘60s, Brian present is the ‘70s, and Brian future was the ‘80s. If you look at the script they’re called ‘Brian Present’, ‘Brian Future’, and ‘Brian Past’. And then a lot of the stuff that happened in the ‘70s was pulled out because he spent four years in bed, not a lot was going on, but it was also demystifying that because he wasn’t really in bed all the time. He was eating and he was doing drugs and drinking and staying in bed and being depressed all the time, but he would walk out of the house in his bathrobe, he would go to clubs, he would listen to music, he would interact with some people, tried to kill himself at the Chateau Marmont. So there were all these things that we ultimately said, ‘Actually if we juxtapose the ‘60s and the ‘80s you get the sense of what happened in the ‘70s’.

Sure, and you tease it too with the film.

MOVERMAN: Yeah. And he talks about it too. One of my favorite corrections in the Brian mythology is when he’s sitting with Melinda and he’s at the piano and he’s like, “I don’t know, it just comes out,” and she says, “I have to ask you, did you really spend two years in bed?” And he says, “It was actually three years,” and then we added that line, “At least that’s what I tell people.” And there were sort of like these little things were there was sort of like a whole mythology about who Brian Wilson is and what his life is, but some of it is real, some of it is based on reality, and some of it is kind of an exaggeration or manipulation of facts or lore that just sort of happened through the years. So we were playing also with the idea that some of it may not be true.

And that’s another thing I wanted to ask you about, which is that when you’re doing a biopic there’s often a line of, “Are we gonna be super accurate, are we gonna be accurate here and play a little looser here?” For people who are curious, what’s the percentage of accuracy versus making a movie?

MOVERMAN: Well that’s a very good question, because you have to be aware of both. You have to be aware of the fact that you want to be factual and you want to be true to the story but you also have to take certain shortcuts, because it took Brian over 70 years to live this life, we have 2 hours [Laughs]. How do you tell that? First you do it by limiting yourself, we’re not gonna tell everything, we’re gonna do this and that, and in our case it was the ‘60s and the ‘80s. And then we’re gonna tap into certain moments in those years, and if you look at the movie, the ‘60s is really a two-year period and the ‘80s is a one-year period that we condensed, it was a longer period in real life. So we started playing with that.

I think everything in the movie is based on fact, everything is based on research, but there were definitely shortcuts that we had to take and different things that we hand to twist around. The Brian/Melinda story, every single scene in that part of the movie happened, because I talked to Melinda and she told me all these stories and I just transformed them into scenes - meeting at the Cadillac Theater, jumping off that boat and swimming - all those things really happened at least in the way she told them. So that was sort of the official story. But when he’s sitting at the piano and he’s starting to talk about Matzah ball soup, I don’t know that they ever had that conversation. But I did read – and that was sort of a tribute to Marilyn [Rovell], his first wife – I did read somewhere and Brian was interviewed and he said, “My first wife was Jewish and I as at the house and that’s where I learned to eat Matzah ball soup” and I thought that’s so weird and kind of completely not part of any kind of story that it has to be in there, because it just gives you a flavor of a moment. He’ll come up with these things out of the blue sitting in the car like, “My brother died.” He just met this person and she’s selling him a car and he saying, “my brother died,’ and you’re like, ‘Ok…’ So I don’t know that these conversations ever happened but I know they’re all in the reality of Brian’s life, what was going through his mind when he was experiencing it, and it was really our job to kind of find important, meaningful moments and play with them and make them work for a movie, knowing that they’re not one-to-one representations of really anything that happened in his life, but they do represent things that influenced him and affected him.

When you did the research, were there one or two things that you took away like, “I can’t believe it, but this is actually true”?

MOVERMAN: All the Landy stuff, all the Landy stuff was just…. I think in many ways the Landy role – Everything in the movie is though, it’s tough to be an actor and it’s tough to portray a real person, and it’s tough to play two people adding up to one person. But I felt the Landy part was the hardest to write, because even though many things that he says in the movie I actually have recording of, in real life he was a cartoon and in real life he was so over the top. You kind of wonder, “Did everybody miss it?” I mean it was so clear, if you watch the Diane Sawyer him done in ’91 I think, it’s so clear the guy is a fraud, a manipulator, out of his mind, probably drugged even more than Brian, and where is everyone? Where is everyone to kind of call him out and say, “Wait a minute, he’s ruining Brian’s life and he’s cutting him away from his family?” All this stuff that he’s doing and I just couldn’t reconcile that they just let him get away with it.

One of the thing that I found recently is the influx of instant communication, the internet, has really changed everything in terms of information.

MOVERMAN: I think that’s very true.

And if this was going on today this would never happen.

MOVERMAN: Right, I think that’s actually very, very true and right on the money. Because I was probably looking at it from today’s perspective and saying, “This guy would be found out in a second!” But back then when there was no internet or cellphones or any of that stuff it was probably easier to isolate Brian and kind of keep him in that arena, represent yourself in a kind of legitimate way to the real world, and yet be involved in all of this insanity. So you’re right, I think that’s explains why it was probably difficult for me, because I was thinking about it in today’s terms about something that happened in a very different time, even though it’s not that long ago.

But it’s also like vintage Hollywood, ‘50s and ‘60s and ‘40s, how you’re able to keep stars’ personal lives more personal because there was no, you know, selfies and whatever it is. Just it’s a completely different way.

MOVERMAN: You’re absolutely right, and that was the leap that we ultimately had to take, which is how to represent it in ways that are somewhat believable even though by today’s standards everybody would point at this guy and say, “That’s a fraud!”

Were you in the editing process at all?

MOVERMAN: Yeah. They were editing in New York which was nice because that’s where I live.

How long was the first cut versus what we’re seeing?

MOVERMAN: You know I don’t remember, but it was longer.

It’s always longer, the question is how much longer?

MOVERMAN: I think the first cut as opposed to the rough cut, the first cut where you’re sort of like, “Let’s have people watch it,” was like 2 hour and 20 minutes.

Oh, so there some missing stuff.

MOVERMAN: Oh yeah. Oh yeah, there always is. What I love about the way Bill approached it is that he was a little bit like Brian in the sense that if you listen to the interviews in full specter where he’s criticizing Brian because he’s very jealous, he calls his music “edit music”. He said like, “Oh, that not real music, that’s edit music.” He sort of put this part and this part and he put it together, that’s not how you do it. Phil Spector is like one take, big sound and it all works together. Brian is like – especially ‘Good Vibrations’ – a little bit of this, a little bit of that, and somehow put it together and that’s what Bill did. He was very open to look at scenes and say, “This scene works this way, but let’s make it work that way and put it in here,” so he was actually creating kind of in a way a Brian composition of like splicing together these things. It took a lot of experimentation. So then we had different versions and different approaches as we were going along and he really trusted the process to ultimately kind of add up to the movie that you see now.

It’s so funny that you mention edit music because that’s all it is today. I’m very curious of what else you’re working on right now in terms of screenwriting, in terms of directing, what’s bubbling up for you?

MOVERMAN: Well I have a movie coming out in September that I wrote and directed called Time Out of Mind.

I was actually wondering what the status of that was.

MOVERMAN: It’s coming out September 11th.

BOTH: Interesting date.

MOVERMAN: Interesting date. Yeah, it happens to be a Friday. I’m very excited about it. It’s about homelessness in New York City and the shelter system and Richard Gere plays a very different character than anything he’s ever played, and you’re really watching a man go through the system, enter the shelter system in New York. We got to shoot in real shelters and it was a real experience so that’s the next thing after this.

What are you working on in terms of spec scripts or just writing in general?

MOVERMAN: A lot of different things, and just kind of trying to find out what the next project is. I’m not really sure. I’m always surprised with how much music means to me, because even after doing Bob Dylan, and Brian Wilson, working on a Kurt Cobain script; I always think, “Oh I don’t want to be thought of as the music guy, so I wanna do something else,” and then I’m always coming back to music. So there’s a Kurt Cobain script that has been around for a bit and I wish there was a way to make it but I don’t know if there is. I’m writing all kinds of projects, I’m just really kind of trying to find my next thing.

Sure. Have you seen Montage of Heck yet?

MOVERMAN: I have, yeah.

I though Brett [Morgen] did a wonderful job with that film, just such a wonderful job. The script that you’re working on, how does it incorporate his life? Is it a chapter, is it a moment?

MOVERMAN: It’s really the 20s in his life, so from 20 years old to 27 and the end. So it’s 7 years of his life. What was interesting about Montage of Heck was that because he used so much of the footage that exists, it actually leaves room for a biopic because when you make a biopic it’s all the stuff that you haven’t seen, there’s no documentation for it, there are no videos of Kurt in these situations. So actually what I was surprised – because I was perfectly willing to watch Montage of Heck and say, “Ok, it’s been done, it’s been told, we’re done. We love Kurt, let’s move on,” but actually there’s a story that Monatge of Heck doesn’t tell about Kurt’s development, his relationship with Courtney [Love], the growth of the band, the changing of drummers, and all that kind of stuff. So there’s all that stuff that I hope I get to do as a film, but if not somebody else does.

What’s interesting is I’ve learned in the last few years the importance of international money to getting a movie made, and I would imagine Nirvana’s popularity and Kurt’s popularity would make it that it wouldn’t be as challenging to make a film.

MOVERMAN: It’s actually not challenging in a financial side, that’s the irony here. It’s challenging in terms of making everything work with the rights. Because there are plenty of people lining up to say, “We’ll finance a Kurt Cobain movie,” because a lot of us are interested in that life and with Montage of Heck even more. So it’s really about finding a way that satisfies the history of the project.

I get it. So basically it’s the balancing of getting Courtney and everyone else involved saying, “You can make this movie.”

MOVERMAN: Yeah, and it’s not just Courtney. Courtney’s been great actually. It’s really a lot of…

It’s corporations.

MOVERMAN: It’s a big world, which is so ironic because Kurt hated all of that.

Yeah. When a corporations’ money is on the line, it’s a complete different world. I’m very curious about the previous films you’ve made, are there a lot of deleted scenes that are just sitting in an editing room vault somewhere that have never been seen? Do you originally have extended cuts that were cut down?

MOVERMAN: Yeah, all of them. I think ultimately that’s the process, but I’m actually not that sentimental about it. I think what happens is you go through this process and you start deleting scenes and changing scenes, and by the time you’re done people will say, “ The DVD is coming out, do you wanna put some deleted scenes on it?” And my answer is always no, because I actually feel like the process eliminated those scenes and they’re just not necessary anymore to tell the story. But every movie has that, this movie has that for sure.

I’m hoping that they put the deleted scenes on this one though.

MOVERMAN: I’m just trying to think of some of the deleted scenes and… [Pause]. Yeah, there might be one or two, but you know what always happens? It’s like when you watch Apocalypse Now Redux, you understand why those scenes aren’t in there.

If there in a separate section it’s still interesting to watch the process.

MOVERMAN: Yeah, I suppose it is.

I gotta wrap but, does your Kurt script have a title?

MOVERMAN: It’s called This Is Gonna Suck.

I like that, and I think Kurt would like that.

MOVERMAN: Honestly, I was just trying to please him. It’s a very strange process to write something about someone who was actually my age, so through the process of doing it I really started feeling like, “Oh I know this guy. I’ve been living with this guy, I’ve been listening to him, we’ve been talking, I’ve been writing dialogue for him,” so when it came to finding a title for it I thought, “Well what’s his whole attitude about this? This is gonna suck!” Which is perfect, I said, “Yes, let’s make a sucky movie about you and it’s gonna suck and it’s gonna be great.”

I like that title a lot. I’m gonna wrap and say congratulations on this movie, really great.

MOVERMAN: Thank you.