Lars von Trier’s depression is well-documented. He’s a visionary plagued by his own personal demons. His fears and phobias have kept him out of the skies and the rush of international film promotion. In 2007 they even led him to say, “basically, I’m afraid of everything in life, except filmmaking.” His depression was so crippling, in fact, that it had made him “a blank sheet of paper” that year, unable to create. Luckily, his struggles did not keep him from the directorial chair. The self-proclaimed “melancholy Dane” returned to work and dug to the very depths of empathy with his harrowing Antichrist, and now he’s dared to display his emotional demons front and center with the apocalyptic Melancholia. My review after the jump:

Many films have destroyed the world over the years – everything from ne’er-do-wells overwhelming a barely livable landscape to epic heroes destined to do the impossible and save the Earth from harm. Our death-defying feats usually know no bounds. We’ll zip into the Earth’s core to get it spinning; we’ll land on an asteroid to nuke it. The demise of planet Earth is so unfathomable to us that we’ll concoct unbelievable plot devices to give ourselves some semblance of control in an uncontrollable situation. Even in a post-apocalyptic landscape, cinema will strive to show something that remains – partial annihilation that offers the slight taste of comfort. But not when Lars von Trier is at the helm of Earth’s destruction. He rips away our cinematic security blankets and offers up a gorgeously tragic glimpse of the end of times.

Melancholia is not here to placate us, to feed into our hopes or cater to our preconceptions. This is the clear story of the end of the world, without pomp or circumstance. Von Trier removes all of the confusion and distraction – carefully created newscasts, end-of-the-world celebrations and/or chaos, panicked shots of people across the world – and focuses on one family, removed from others and dealing with the inevitability and denial of the end.

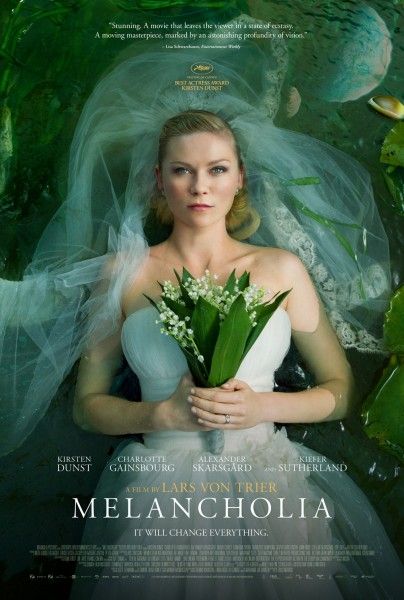

After a montage of chillingly beautiful images as Melancholia prepares to engulf the Earth (well-documented in the films pre-release push), the film is split into the story of two sisters. First, Janine (Kirsten Dunst) and her wedding to Michael (Alexander Skarsgard), and then Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg) as she faces Melancholia with her sister, husband John (Kiefer Sutherland), and child Leo (Cameron Spurr). As Janine heads to her reception with Michael, she seems happy, even as their stretch limo gets caught on a winding road. But things begin to unravel when she faces her deeply troubled family and notices a bright star that disappears from the night sky. It’s as if recognition of Melancholia cracks her carefully constructed demeanor, and her own sadness pours out.

As the party plays out, and Justine is faced with emotionally stunted and jovial father (John Hurt), a seriously deleterious mother (Charlotte Rampling), an obsessively demanding boss (Stellan Skarsgard), and an impatient brother-in-law, her hold on sanity and levity breaks. Her rapidly elevated depression seems to be, at once, a result of the insidiously negative environment she is in, and her own internal struggles as she repeatedly leaves the party, separating herself from her guests, family, and even husband. The wedding planner (Udo Kier) is so disappointed in the event’s outcome, in fact, that he can’t even bring himself to look at her.

When the wedding is over, all the extraneous players are removed, planet Melancholia approaches, and the camera focuses on Claire. She’s struggling to deal with her sister’s now debilitating depression and her own growing fears that despite her husband swearing to the contrary, Melancholia will collide with Earth. As the imposing planet moves closer, each deals with the event in a different way. Claire panics and makes contingency plans, picking up mysterious pills from the village; John is intellectually invigorated, studying the phenomenon and pulling his young son into the fervor; and Justine begins to grow more comfortable and capable as the danger increases.

Obviously, this is as much a metaphor for depression as it is science fiction. Planet Melancholia is an imposing, engulfing presence that cannot be avoided. As we traverse Justine’s wedding, we might feel empathy or aggravation. In a world and life with no exact end, there’s a freedom to choose and condemn, to feel like there’s a point to it all, to have the cockiness of positivity. When destruction is inevitable, however, there’s no room for contrary opinions, for a feeling of emotional wellness and superiority. Everyone must deal with the melancholia – the sudden certainty of their demise and the overwhelming sense of dread.

And we feel it too. Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde” scores the melancholic tale, and the rumble that submerges the audience is quite similar to the beginning of Wagner’s “Siegfried’s Funeral March.” Von Trier plucks a myriad of emotions from us, merging slow-motion, deeply stunning visuals with shaky, hand-held camera work that exacerbates the characters’ feelings of unease. Yet the oppressive disconsolation is tempered by a layer of loving nostalgia. The orchestral backdrop invokes memories of classic Hollywood, becoming all the more powerful when von Trier replicates iconic imagery – Kirsten Dunst becoming the doomed Ophelia, or resting naked by the lake. In all of this family’s self-involved angst, there is still this palpable feeling of the past. Though we don’t see the world at large, we’re given reminders of the beauty that’s about to disappear.

But as much as his style and personal experience fuel the story, Melancholia doubly thrives as a vehicle for its actors, especially Kirsten Dunst. Watching her as Justine melts away every bad or questionable performance that has plagued her career. Dunst quite perfectly thrives as Justine, as if there was little to nothing between her sensational premiere as the vampire Claudia and her tragic, depressed heroine facing the end of the world. She evokes a classic, silver-screen sense of ivory beauty while also oozing the painful depression required of her.

Lars von Trier is a skilled master of simplicity and the art of audience manipulation, and it’s usually to give us a social and political message, whether spending time with The Idiots or pulling great social truths out of a barren stage for Dogville. But Melancholia isn’t about politics or the greater world. It’s about the fear, pain, and overwhelming dread that accompanies depression; and it’s about leveling the playing field. To truly understand von Trier’s melancholia, we must feel the hopelessness and futility, and there’s no better way to do that than by ripping our world away, our security blanket that tells us that life always goes on.

For all of our coverage of the 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, click here.