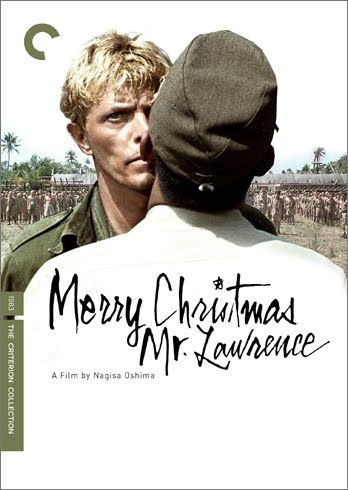

Few film genres cover such a wide range of perspectives and styles as do those about war. War movies range from those that glorify combat to those that reveal its deepest, darkest horrors; from those that take place direct on the battlefield to those that revolve around ancillary elements; and from those that are intensely patriotic to those that are pointedly critical of one’s own nation’s actions. Nagisa Ôshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is a “war” film that explores the intense conflict between different cultural mores when those very mores themselves are being challenged by the brutal realities of a world at war. My review after the jump:

Masquerading as a war movie, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is an intense character study that takes place in a Japanese POW camp during World War II. The film focuses on the interconnected relationships of four men: Colonel John Lawrence (Tom Conti), a British officer who has spent time in Japan, speaks Japanese and is thus able to bridge the cultural divide; Major Jack Celliers (David Bowie), the new prisoner whose rebellious nature threatens to disrupt the delicate balance of the camp; Sergeant Gengo Hara (Takeshi Kitano), a brutal soldier representative of how far the Japanese military has swayed from its own code, but with whom Lawrence has developed a strange friendship; and Captain Yonoi (Ryuichi Sakamoto), the camp commander whose inner conflicts are manifested by the outer conflict between Japanese / military morals and actual brutality around him.

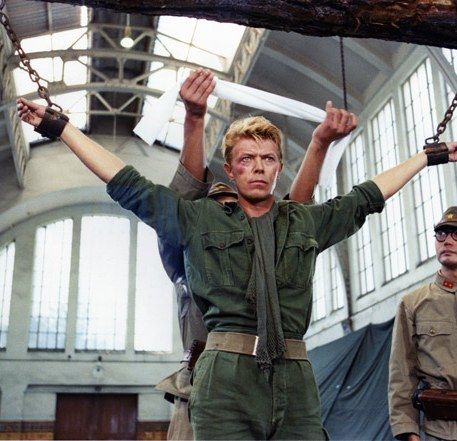

Although Bowie is the most recognizable face to Western audiences, Mr. Lawrence is a Japanese film and thus ultimately Hara and Yonoi are the most dynamic and interesting characters. Their paths are divergent. Yonoi initially saves Celliers from death at the hands of a kangaroo court, thus standing up for traditional Japanese honor in the face of it breaking down around him. His own fascination with his new prisoner—which at the very least has to do with him having a like code, a similarly haunted past, and possibly even homosexual overtones—transfers real psychological power to the British major even while Yonoi thinks he is maintaining physical control. As Celliers’s rebelliousness increases, Yonoi descends into the very violence and false justice he formerly stood against, and when Celliers shames him with a kiss, Yonoi’s defeat is complete.

The brutal Hara, on the other hand, maintains ongoing philosophical discussions with Colonel Lawrence, rationalizing his own violent actions as actually being in line with true Japanese values while claiming to fail to understand the British, their morals and their actions. But it is he, on a night of heavy drinking that may or may not be influencing his actions, that releases Celliers and Lawrence on the eve of their planned executions in direct contradiction of Yonoi’s orders. Four years later in 1946, on the eve of Hara’s own execution, Colonel Lawrence visits Hara in his cell in the film’s epilogue. Celliers and Yonoi are both long dead, but Hara is a changed man, at peace with himself and his impending death, fully redeemed. He once again wishes his unique friend, “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence”.

The performances are riveting throughout and the cinematography captures the look—minus any graininess—of World War II period combat footage as well as any I have seen thus adding a very real quality to the narrative. At the same time the film features a compositional symmetry that borders on disconcerting because of its very unusualness. Where one might normally expect a subject to be framed 1/3 of the way across the screen leading into the action, in Mr. Lawrence that subject would be perfectly centered. This “off-putting order” perfectly mirrors the central conflicts of the film.

The one element of the movie that simply did not work for me was the score composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto. Although I can appreciate it as a standalone piece of music, the 1980s pop sensibilities felt incongruous to me in a 1940s period piece. I think the movie would have been better served with an era- and region- appropriate score, or at least a timeless style of music that isn’t so pointedly from another time.

This being a Criterion Collection release, the film has been beautifully restored. The picture is pristine, and while the audio exhibited somewhat of a hollow quality, that was obviously resulting from how it was recorded and mixed, not any deterioration of the elements. The extras exhibit the usual degree of thought and care that one expects from Criterion, including a mix of both archival special features (a 1983 making-of featurette entitled The Oshima Gang and a 1996 documentary, Hasten Slowly, about Laurens van der Post upon, whose novel the film was based) and newly shot interviews with Conti, Sakamoto, screenwriter Paul Mayersberg and producer Jeremy Thomas. All have been selected to inform and further one’s understanding of the film and those involved; none of the visual or informational fluff of a studio release.

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is a fascinating character study, and one of the most interesting “war” movies I have seen in a long time.