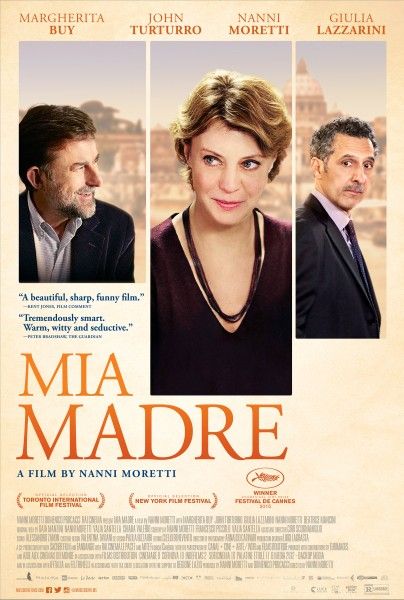

Collisions run their course in Mia Madre, a semi-autobiographical film from Italian director Nanni Moretti (The Son's Room), not the least of which is a tonal clash. While that's an easy recipe for aimless disaster, the film carries itself with a whimsical nuance without ever falling victim to an identity crisis. The mood of Mia Madre is a generally somber one, as the film focuses on a director, Margherita (Margherita Buy)—loosely based on Moretti himself, except played by a woman—who is shooting her latest film while consumed by worries of her dying mother. But for a drama about death, it's also incredibly funny—not just wry funny, but also body humor funny—making for an interesting mix. Moretti is able to pull it off masterfully, and with heart.

The semi-autobiographical aspect here is that Moretti's own mother passed away while he was filming his 2011 film Habemus Papam; thus the film's fictional mother Ada (Giulia Lazzarini) becomes a tugging conscience at every moment, even when Margherita is on the job, though her film—about a workers strike at a factory—is nowhere near reminiscent of what's actually happening in her life. Moretti (who won a Jury Prize at the film's 2014 Cannes debut) has a tendency to include himself in his own films, and he does so again here, playing Margherita's brother. Though they're both distressed by their mother's illness, he removes the personal baggage off himself and puts all the emotional weight on Buy. Moretti, instead, plays the level-headed anchor of the two, which at times amplifies Margherita's guilt about her inability to work less and spend more time with her family. The relationship between the siblings never feels forced, though; rather, it is a quiet, subtle one, of mutual understanding and support.

On the other hand, not so subtle is Margherita's relationship with the star of her movie, a foolhardy American actor played by John Turturro (in one of this year's best performances). Turturro's Barry Huggins is easily the comic relief, but he proves himself to be more than just vapid caricature. Turturro's character, as frustrating as he is, is the most delightful one to watch (there's a brief dance scene that alone is worth the price of admission). He constantly forgets his lines, is terrible at pronouncing Italian words on the rare occasion he doesn't forget them, and becomes the volatile on-set presence that always drives Margherita to the edge.

Even in full-on shouting matches, Turturro brings a sense of humor as Barry, chest-puffing as he talks about having worked with Stanley Kubrick (a huge stretch, as Margherita points out), and how this film is beneath him. Turturro is a stand-out in the film, often laugh-out-loud funny based on the ridiculous nature of his character, but he also, weirdly, proves to be the mirror of Margherita's own anxieties—anxieties about incompetence and helplessness that bubble up at both of their outbursts. His, of course, contain a lot more ego.

Moretti, as a filmmaker, isn't an egotistical one, though. He's generally less interested in flashiness and amongst the most subtle brilliances of the film is the way he brings us into the film, then into the film within the film—or vice versa—often confusing which reality we're in. It happens with the opening sequence of the film, and even a few throughout—until Margherita yells "cut"—but it also happens with Barry, whose real-life brashness gets blurred with his loose commitment to "staying in character." There's a scene where he yells at the crew that the on-set champagne should be real champagne, to which they react with nervous chuckles and panicked confusion, before the actor breaks the ice with hysterical laughter. Even in these comic moments, these layers of reality make the viewer consider Moretti's intentions with the film, and his bond with it. Films within films may as well be dreams within films, and there are those too—equally as sad and mundane as Margherita's real life.

If there's one under-explained aspect, it's that Moretti doesn't do a very good job addressing the political meaning behind Margherita's film. As every dream has a meaning in a film, this one probably does too (underdeveloped political commentary?). But perhaps that's not even that important. The director seems to care more about the family drama, and wise choice—it resonates in a way that perhaps socioeconomic commentary wouldn't, and it lets its players shine, with standout performances from both Turturro and Buy.

Grade: A-

Mia Madre opens in select cities Friday, August 26.