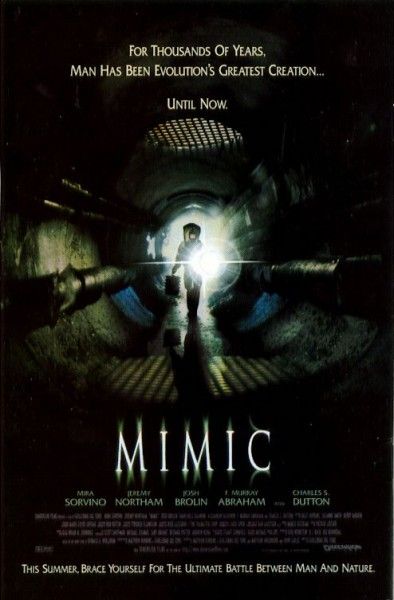

[With Guillermo del Toro’s new movie Crimson Peak opening next Friday, I decided to take a look back at the director’s filmography.]

I believe we are shaped by our failures as much as our successes, and Mimic is, by the filmmaker’s own admission in the Director’s Cut commentary track, a defining failure for Guillermo del Toro. He refers to it as “a cautionary tale,” but one that strengthened him as a director not only in his temperament, but artistically as well. It’s a movie that’s been compromised six ways to Sunday, and you can feel how those compromises wore away at what could have been a better film, although even at its best, Mimic feels surprisingly cynical for del Toro.

Despite the strong cinematography, Mimic is never inviting towards the audience and almost seems to aggressively put us at odds with its ethos and characters. It’s a movie cloaked in condemnation, and even in del Toro’s dream version that never made it before cameras, the arc of the story is amoral insects taking away humanity’s place at the top of the food chain. While this mimicry does play into del Toro’s oft-repeated theme of monsters and men, humanity is sorely missing from the overall picture.

Mimic: The Director’s Cut is the best product del Toro felt he could assemble from the footage he had, and, as he stresses repeatedly on the commentary track, also involved removing pretty much everything that was shot by second-unit. The film may be a mess, but it is his mess, and it’s a mess that begins in fits and starts.

We’re introduced to a plague, which is quickly eradicated by the “Judas Breed”, a termite-mantid hybrid created by Dr. Susan Tyler (Mira Sorvino) and deployed by her husband/CDC deputy Dr. Peter Mann (Jeremy Northam). The bug kills the cockroaches carrying the virus, but then we jump ahead six months to Tyler and Mann having their day in the sun (although the CDC can’t afford to put its chief scientists up in more than a dingy hotel for some reason) then one year forward, and then three years forward.

These stacked prologues help explain how the bugs have had time to reproduce at an astonishing rate, but we don’t get much in the way of character development, and we certainly don’t get any mythologizing. Del Toro certainly did his research when it came to insects, but for a film that’s hung up on explaining things to the audience, it rarely does a good job of explaining necessary behavior. On the one hand, I agree with del Toro that not everything needs to be spoon-fed to the audience; on the other hand, if your bugs kill some kids but not others, and the reason is because one didn’t exude any fear chemicals, that’s a distinction where you have to assume your audience could use some education on insect biology.

But plotholes like the bugs not killing Chuy (Alexander Goodwin) or Susan when they have the chance are minor in the scheme of a picture where del Toro fought with producers so often that he was happy to have victories like Mann keeping his glasses. The larger problem with Mimic is that it lacks the personality and verve of del Toro’s other pictures. Although it’s not del Toro’s fault that the movie was locked into being a B-picture about giant cockroaches (an early meeting with the producers basically changed the mimics from ghostly white insects to huge roaches), it’s an oppressively dour picture that has almost no investment in the characters or their struggle.

Moreover, Mimic isn’t about mythology or world building. There’s nothing ancient in Mimic. While other del Toro films revel in the mysteries of the past, Mimic takes a depressing look at the present, or at least it does in del Toro’s original intent, which is that the bugs would rise up and replace man. The hints of this vision remain primarily in the loose religious allegory del Toro drops in like the dead priest, the shit-caked cathedral, the knock on the “Jesus Saves” sign, and even calling the bugs the “Judas Breed”. Like Cronos, there’s no interest in a deeper examination of faith, but the religious iconography serves a thematic purpose, although in Mimic it could never be fully realized because of all the interference del Toro faced from various executives.

And yet even if Mimic had stayed true to del Toro’s original vision, I can’t help but wonder if the benefits of a short-term success would outweigh the value of this long-term failure. “It was Mimic that defined the ethos of filmmaking for me,” says del Toro on the Director’s Cut commentary track. Was the artistic vision behind Mimic—one where giant bugs ultimately defeat humanity—ultimately better than how it shaped del Toro for the next twenty years? We’ll never know, but the value of Mimic can’t be understated simply because the film taken on its own merits is a failure.

It’s a movie where we never particularly care about any of the characters, probably because they’re the fuck-ups who caused the problem in the first place and who openly say at one point, “We don’t know what we did!” (Between this and The Strain, which came out two decades apart, I don’t think anyone has a lower estimation of the CDC than Guillermo del Toro). I don’t mind del Toro siding with monsters, but he has an extremely low opinion of humans in this movie, and the story doesn’t have much justification for it. There’s a coldness to the proceedings, and perhaps that’s born out of anger or confused messages, but I find his original intent for Mimic at odds with what makes him such a great filmmaker.

What he views as the movie’s best moments, like Leonard showing the power of humanity by choosing to sacrifice himself (heroic self-sacrifice is a frequent trope employed by del Toro), comes off like yet another movie where the minority character dies to save the white people. The movie abhors science, but it doesn’t have the refuge of the mystical like del Toro’s other movies. It’s an angry little picture, and that’s in its “best” incarnation.

But what makes Mimic better than its actual movie is how it taught del Toro to be a stronger filmmaker. David Fincher had a similar trial-by-fire on Alien 3, and you can see how these early struggles in a filmmaker’s career helped shaped him to do better work. That’s not to say that a filmmaker can only become great if a studio absolutely screws him or her at the outset of his or her career, but that adversity is key in figuring out how to conquer those problems when they inevitably pop up later down the line.

For del Toro, he learned that Mimic was about “fucking up on my own terms,” and that’s part of what comes with being a visionary. It’s why a director’s work is more rewarding when cast against an entire body rather than on its own merits. Mimic didn’t happen in a vacuum, and while its success and failure ultimately lie with del Toro despite the meddling involved (in the commentary he says that the “buck stops with me”), it becomes a rich, fascinating picture when you see how much he grew as a filmmaker from Cronos to Mimic even though his leap forward as a storyteller wouldn’t become apparent until his breakthrough feature several years later.

Tomorrow: The Devil’s Backbone

Other Entries: