I don’t envy Andy Serkis’ task of doing a live-action, motion-capture version of The Jungle Book after Disney beat him to the punch in 2016 and picked up almost a billion dollars worldwide along with an Oscar for Best Visual Effects. Being first is tough enough in Hollywood, and then you have to compete with a movie that was a massive success. But comparisons to The Jungle Book aren’t what hurt Serkis’ Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle as much as his desire to take the adaptation in an incredibly dark direction. Even if you make the argument that Ruyard Kipling’s source material is dark in and of itself, there’s still a leap to what we’ve come to expect from a Jungle Book movie. It’s a story that’s ostensibly for children, but Serkis has covered it in blood and anger, which would be fine, except the darkness doesn’t really seem to serve anything. If anything, it just makes Mowgli a more uncomfortable experience coupled with visual effects that are more distracting than immersive.

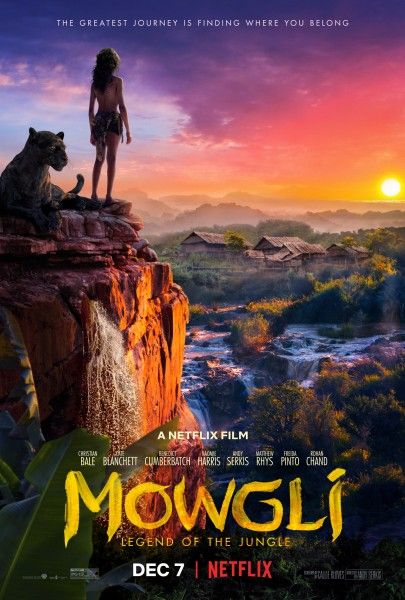

The adaptation follows the same basic beats of The Jungle Book—an orphaned baby, Mowgli, is adopted by a pack of wolves and becomes the “man-cub”. He’s taught to survive in the jungle by Bagheera (Christian Bale), the panther who found him, and Baloo (Serkis), a good-natured but lackadaisical bear. However, the presence of Mowgli (Rohan Chand) in the jungle causes the ire of Shere Khan (Benedict Cumberbatch), a tiger whose only goal in life is to eat the man-cub. This causes conflict among Mowgli’s protectors. Among the wolves, it’s deemed that Mowgli is never truly part of the pack, but Baloo thinks that if Mowgli can pass the necessary tests, the pack will protect him. Bagheera believes that Mowgli’s safety lies with joining a nearby village of humans because Khan won’t go near people. In the middle of this conflict, Mowgli must decide if he belongs with men or if he’s part of the jungle.

Skirting around the outside of Mowgli is a fairly interesting refugee story, specifically how refugees impact communities. To some, like Baloo, Bagheera, and Mowgli’s wolf-mother Nisha (Naomie Harris), a refugee like Mowgli is to be protected. He has no people of his own, and it’s the duty of the community to look after the individual and help him assimilate into their culture. But for others, like the less-than-accepting wolves in the pack, Mowgli is a refugee who only brings trouble with him. Unfortunately, the narrative of The Jungle Book brings the subtext to a disappointing conclusion with the hero’s arc necessitating that Mowgli, the refugee, must prove his value to the community before earning their acceptance rather than gaining that acceptance because it’s good to help people who need help.

However, even if the movie had landed its theme, it would be difficult for it to break through the overpowering darkness that devours the entire picture. I never really needed to see Baloo covered in blood after fighting off a bunch of ravenous monkeys, but I got it with Mowgli. It’s a movie that constantly leans in towards violence, but that violence is removed from danger because Mowgli is surrounded by CGI characters. A book can make the characters dangerous because they’re crafted by your imagination, but when you have to commit them to the screen, a talking animal seems far less scary. Perhaps with a stronger story or adaptation (I have more faith in something like Animal Farm being adapted because it’s overtly political), the blend of darkness and talking animals could work, but here, it’s constantly jarring.

Serkis isn’t helped by the CGI animation that makes the incredibly bizarre choice to give all the animals human-like eyes. This makes the characters dwell even further in the Uncanny Valley and this is on top of the questionable composition work where none of the characters seem to be occupying the same space. Trying to reach the level of Disney’s Jungle Book is a tall order, but before Mowgli was going to be released by Netflix, it was a Warner Bros. movie. Warner Bros. has money! And yet this looks like the lo-rent, direct-to-DVD version of The Jungle Book, and I suppose now that it’s arriving on Netflix, its distribution fulfills the destiny of its visual effects.

There are things that Mowgli is trying to prove. It’s trying to prove that The Jungle Book isn’t just a story for kids and that it can be handled in a mature, aggressive way. It’s trying to prove that motion capture isn’t just for luminaries like Serkis, but that it can work for Oscar-winning actors like Christian Bale and Cate Blanchett (who plays the snake, Kaa). But Mowgli never proves these things because the execution is always off. It’s tough to buy Bale’s performance when Bagheera’s animation rarely conveys emotion. It’s tough to understand why we need a blood-soaked Jungle Book when that violence doesn’t tell us anything new about the story. Mowgli is undoubtedly different than 2016’s The Jungle Book. Unfortunately, none of those differences are to the movie’s credit.

Rating: D