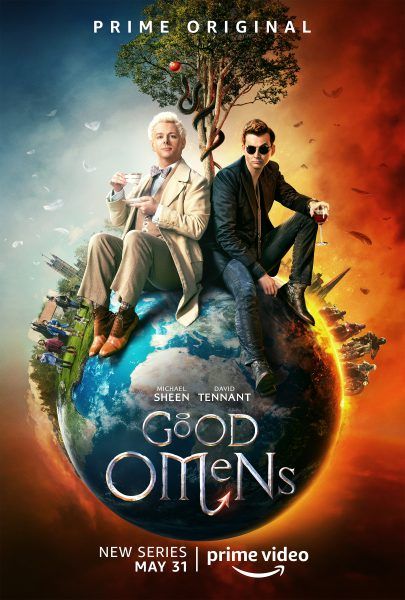

When the armies of Good and Evil start to gather together, and the Four Horsemen get ready to ride, it seems as though it’s safe to assume that the Apocalypse is coming and the world is about to end. But when it comes to the story that Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett created for Good Omens, and that Gaiman has brought to life via a six-episode series (streaming at Amazon Prime Video), nothing quite goes according to plan, and the unlikely duo of Aziraphale (Michael Sheen) from Heaven and Crowley (David Tennant) from Hell set out to find the currently misplaced young Antichrist (Sam Taylor Buck) and stop Armageddon before it’s too late.

While in Los Angeles to promote the series, Collider was invited for an extended 1-on-1 chat with showrunner/writer/executive producer Neil Gaiman to talk about revisiting the story of Good Omens three decades after the release of the book, why he wanted to make this series for Terry Pratchett, the difficulty of bringing this story to the screen before now, what made Douglas Mackinnon the right director, how he came to Michael Sheen and David Tennant for his unlikely duo, and getting Benedict Cumberbatch to voice Satan and Frances McDormand to sign on as God. He also talked about the long and winding journey to still trying to develop adaptations of The Sandman comics and The Graveyard Book for the screen.

Collider: This is such a great story and such a fun show. What was it like for you, especially having released this book 30 years ago, to be revisiting the material, in this way?

NEIL GAIMAN: It was wonderful, and it was a bit weird.

It seems like an unusual circumstance that doesn’t happen very often, that you get to be the showrunner for a TV series that you adapted from your own book.

GAIMAN: I wouldn’t have done it, if it wasn’t for Terry [Pratchett]. As far as I was concerned, what we should have been doing was finding someone to adapt and showrun Good Omens, except Terry asked me if would do it because we couldn’t find anybody who would take it on. People thought it was too weird or too complicated. Nobody said yes. Terry asked me to do it, and I said yes because Terry never asked me to do anything before. And then, he died. I thought we had lots of time, and he went very suddenly. I left his funeral, flew back, and started writing Episode 1, as a way of dealing with somebody who’s been such a huge part of my life not being there anymore. It was interesting. I did Good Omens very differently to the way that I normally do things, where I’m affable and easygoing and people say, “Oh we’re going do this,” and I’m like, “Okay. Well, good luck. Go have fun with it.” With this, I was making it for Terry. So, when producers said, “We’ve figured out a great way to save an enormous amount of money. We think you should do the Agnes Nutter sequence with a narrator talking over illustrated woodcuts,” I’m glad to say it didn’t happen. But that was also because I’d given myself the power to say yes or no to things. That drove some of the people at the BBC mad because they weren’t quite sure what a showrunner was and why I was one. I said, “Actually, you just have to listen to me, on this one.” I was lucky, in that I had a fantastic, wonderful director, Douglas Mackinnon, who really got what we were doing. We were just so lucky. Good Omens has given me the two best collaborations of my career. It gave me Terry Pratchett, and it gave me Douglas Mackinnon.

How did you decide on Douglas Mackinnon, specifically?

GAIMAN: Douglas had directed some wonderful stuff, including the Emmy award-winning episode of Sherlock, set in Victorian times. But the thing that I had fallen in love with Douglas for was Jekyll, which he wrote. It was a wonderful Steven Moffat project, which never got the attention or acclaim that it should have. What I loved about Jekyll was that the funny stuff was funny, the scary stuff was scary, the romantic stuff was romantic, the spy stuff was spy-ish, and the mysterious stuff was mysterious. There was no point in it where a director tried to homogenize it. Years and years and years ago, when I was doing Neverwhere for the BBC and interviewing directors, I remember directors coming in and saying, “The scripts are all over the place. They’re funny, there’s romance, there’s adventure, there’s social commentary. You have to pick one and stick to it. Just make it one thing.” And I was like, “No. The whole point of this thing is not only that it’s going to contain multitudes, but it’s only going to work, if we commit to every multitude that it contains.” There’s no funny acting in Good Omens. The whole point was that we didn’t actually want people doing the funny acting. We wanted people doing their serious, emotional, committed acting, and we figured that the funny would take care of itself. And Douglas had that. I remember the first interview with Amazon – and there were people, back then, at Amazon who are no longer at Amazon – and they very much were of the opinion that they didn’t want Douglas. What they wanted was somebody with an Academy Award for directing a movie. I was like, “No, I really want Douglas. I think he can do this.” I remember them asking Douglas, “Well, what’s the tone of Good Omens?” And he said, “There will be no tone to Good Omens. There will be absolute commitment to every scene that Neil has written. You get scenes that are from a spy novel, you get scenes that are from an adventure, and there’s romance. There’s everything in there, and that’s what we’re committing to, tonally.” We did that, and it worked.

It does. I also cannot imagine anyone other than David Tennant and Michael Sheen playing Crowley and Aziraphale. Was that the case for you? Had you imagined anyone else, or was it always them?

GAIMAN: It was always them. Having said that, before I started writing, I imagined Michael as Crowley. I started writing the scripts and rapidly went, “No, I want Michael as Aziraphale. The loveliness of Michael will be brilliant.” And then, I decided that I wanted David Tennant while writing the script for Episode 3, during the bit where he’s coming down the aisle of the church and he’s on consecrated ground, and he’s hopping from foot to foot because it’s like being at the beach with bare feet. I was like, “Who could do that?” And I suddenly thought, “Oh, David Tennant. He could do that in silhouette, and it would work.” Suddenly, I had my Crowley and my Aziraphale. And then, I needed to convince people, not for Michael, but for David. There was definitely a period of time where they were like, “Well maybe we can get . . .” These were people who were at Amazon then, who are no longer at Amazon, but they were like, “Maybe we could get Johnny Depp and Brad Pitt.” And I was like, “But I don’t want them. They’re wrong for this. They’re wonderful, but I don’t want them.” So, there was a definite trying to talk people down from the stars’ ledge, to give me the actors that I wanted.

I also think Jon Hamm was a great choice, but an unexpected choice.

GAIMAN: Isn’t he lovely? I chose Hamm for two reasons. Firstly, I wanted somebody who was the boss that you hate. He needed to be better looking, better dressed, taller, bigger and more imposing than Aziraphale, in every way. And I happened to know that Jon Hamm was a fan. He told me that American Gods and Good Omens were his favorite books when he was at college. I wrote him an email that said, “You once told me that Good Omens was your favorite book and that you thought it was un-filmable. I would love to have you play Gabriel in Good Omens. He’s not in the book, but will you do it?” And I got back an email from him that said, “Yes. Hamm.” Casting was mostly really, really easy because the book has generated an awful lot of good will. They’re fans and they wanted to be a part of this, and that makes me so happy.

Seeing this series, it seems like it would have been impossible to have made a film instead. Do you feel like that was part of the problem with it never going into production before?

GAIMAN: I think so. I also think that Terry Gilliam going to Hollywood to try to sell them on a Good Omens movie, three months after 9/11, was also part of the problem. I would’ve loved to have seen Terry’s movie. It would have starred Johnny Depp as Crowley in 2002, and Robin Williams as Aziraphale and Madame Tracy. It would’ve been great, but I’m glad it wasn’t made. I’m also glad that we said no to all the TV series that people wanted us to make, back in the 90s, because technology couldn’t have done this. We wouldn’t have had the budget. We wouldn’t have made it look like this. It would’ve been Doctor Who, and that wouldn’t have been good. We are so lucky. Visual effects needed to get to the point that visual effects are at right now. And I’m not talking about the obvious things, like Crowley driving around in a burning Bentley. I’m talking about things, like our street in Soho, which is a set that becomes a street. It’s absolutely invisible to the eye. I know where the street ends, and I’m still astonished and amazed at knowing how much of that is digital. It just looks like we closed down London to shoot for a week. Douglas did some things that were magic.

How challenging was it to find a group of kids that could do everything you needed them to? They’re all so great in the series.

GAIMAN: They really are. We had a fantastic casting department, who basically went out and narrowed down all of the child actors in the UK to about 20 people. Douglas went out and worked with those 20 for a day, and took them down to about eight. And then, we went in and watched the eight go through their paces. It was interesting because Adam, for example, was down to two kids. Sam Taylor Buck and another kid. The other kid was amazing, and landed every joke. Sam didn’t really land the jokes, in the same way, but you believed him and, when he got angry and scary, he was absolutely terrifying, whereas the other kid was suddenly a shout-y 11-year-old. If you didn’t believe that this kid has the power to end the world, nothing was going to work. He’s amazing. All of them are so good. Our little Wensleydale (Alfie Taylor) is fantastic. Ilan [Galkoff], who plays Brian, is the linchpin of those four. We always knew that we could cut to Brian for a reaction shot. And then, Amma [Ris] just is Pepper. I wrote a bunch of that dialogue for her and was worried that it was going to be too on-the-nose. I thought, “Can I actually have Pepper say ‘I do not endorse every day sexism’?” But I could, and it worked just fine because she delivered it. I love those four kids. I want to see where they are, in four years time, and I want to see what they are in 10 years time, and I want to see what they are in 15 years time. Some of them may well stay in acting and some of them may be stars, and some of them may go, “Okay, well, that was a thing I did.” They’re all amazing. The kid who plays Warlock (Samson Marraccino) is just marvelous.

How cool is it to have Benedict Cumberbatch as Satan and Frances McDormand as God?

GAIMAN: The last person we cast was Ben. We’d been doing Satan with a voice track, by somebody who couldn’t really act, but was just doing a slight monster-y voice that wasn’t working, and that was me. We knew we were going to have to go out to somebody else, so I was like, “Okay, let’s start at the top.” Who doesn’t want to voice Satan, when you know that Frances McDormand is God? Ben said yes, and then Douglas filmed him while he was acting and we sent that little iPhone file over to the visual effects people, and it’s beautiful. And Frances said yes to doing it with a comment about the fact that this would finally demonstrate to any members of her family, who were doubtful that she was, in fact, God, and that members of her family who have been claiming that she believed herself to be God would now be proved right.

With so much great material, how hard was it to get this edited down to the episodes that we see now?

GAIMAN: There were scenes that were cut, that we were fighting for, even after they were cut, which is normally impossible. There was one scene that we cast, and the whole plan was to come out to L.A. for a day and shoot some stuff, but we just couldn’t get it together. The money was there, and then it wasn’t there, and then it was there, and then it wasn’t there. In the end, it wasn’t there. There are only maybe two scenes that I miss.

It seems like, in some form or another, your work is always being talked about as being in development, and that seems to be the case with Sandman and The Graveyard Book. Is anything on the horizon next, or are things always just in a state of waiting to see what will happen?

GAIMAN: Great question. There are definitely things that get made when the time is right. I don’t think it would have been possible to make a good Sandman, when they started trying to make a good Sandman. [Ted] Elliott and [Terry] Rossio wrote their first Sandman scripts in 1996. At the time, I was looking at it and going, “This is impossible to make. Nobody is going to spend $100 million on an R-rated, effects-heavy, cerebral fantasy story. It can’t happen.” At least not back then. But on the other hand, I’ve gone through 25 years of people saying, “So, Sandman is going to get made now.” I’ve learned to go, “Yeah, okay, I’m looking forward to it.”

With The Graveyard Book, that makes me sad. It was sold to the Walt Disney Company because Henry Selick, who made Coraline, was at Pixar, at the time, and wanted to make it. They were going to make it as Pixar’s first adapted film. It was going to be stop-motion animation, like Coraline. I was really excited. That was why I went there. Then, Henry wound up leaving with a film that he got half-way through and then abandoned, and it was closed down by Alan Horn. Since then, every 18 months, the same cycle has been happening, where they tell me that they’ve got a new writer on it. Then, a few months later, they send me a script and it’s okay. It’s 75% of the way there. It reads a lot like the last scripts that were done. And then, they tell me that they’re out for a rewrite. Normally, I don’t get sent the rewritten script. They just tell me, “No, we don’t really like it. But we’ve got an idea for a writer who’s going to really nail this.” And then, a few months later, they tell me that they’ve hired the new writer, and it begins again. That’s been happening since they bought The Graveyard Book. I really hope that they make it, and that they make it into something good. I would be perfectly happy for The Graveyard Book to be a TV series. I wouldn’t mind. I’d also love it to be a fantastic movie. That would be wonderful.

I love that story, as well as Clive Barker’s The Thief of Always, and I would love to see both of them get made as movies.

GAIMAN: I’ve read some great scripts, over the years, for The Thief of Always. There was a fantastic script, and they asked me if I would look at tarting it up. I read the script because I was interested, and I said, “This is great. There’s nothing I can do. I’m not going to randomly change it for you. It’s terrific.” I want to see a really good The Graveyard Book movie. The important thing for me with Good Omens was not that I made Good Omens. What was important was that I made a fantastic Good Omens book. It’s a beloved book. It’s not just a best-selling book, it’s a beloved book. People who love Good Omens have five copies because they keep lending them to people, and they’re really battered. It’s this thing that they care about, and they love, and they think about it. It’s 110,000 words long, but the amount of fiction written by fans dwarfs Good Omens. There must be millions upon millions of words written because of it. So, the idea of making a TV show, for the sake of making a TV show, was not something that I wanted to do. I wanted to make something that would make people go, “Oh, my god, I love that so much.” And everything about making Good Omens was that for me. It’s what makes Michael McKean magical. It’s what makes Miranda Richardson magical. It’s what will make people look at Jack Whitehall in a completely new way. It’s Adria [Arjona] proving herself a mistress of comic timing. And the kids are so cool.

Good Omens is available to stream at Amazon.