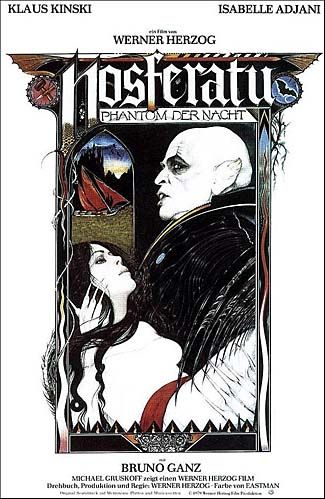

Towards the end of Werner Herzog’s remake/reimagining of Nosferatu, pseudo-Mina-stand-in Lucy** (Isabelle Adjani) wanders outside through a crowd of revelers, basking in dance and each other’s company. The rub here is that in the background of all this merriment – half-discarded coffins and lost crud-stained pigs roam unnoticed. Lucy finally comes to a stop, noting an upper-class family enjoying a lavish dinner outside. The family gobbles platters of grub while delicately sipping their goblets of wine; however underneath the elegantly carved wooden table the family dines at, hundreds of rats scurry along nibbling at their bare feet. The imagery here clearly gets at the bleak nihilistic heart of Herzog’s picture: life just a series of distractions from the cold inevitability of death. All the joy and cheer of existence – a simple means for laymen to wish away and ignore their own impending insignificance. Hit the jump, to continue reading.

It’s a fairly obvious point, but most interpretations of the ‘Dracula’ mythos tend to focus on the underlying vitality of the undead, an ironic duality that dates from Bela Lugosi’s Dracula to even this year’s short-lived NBC version. The gist of the vampire’s appeal hinges on just how similar he is to you and I. In fact – he is, if anything, more human. An unleashed ‘Id’ of hyper sexuality and pure will. Dracula, unlike any other movie monster, is the guy you wish you were: a rich handsome fella able to woo any girl he wishes with nary a glance. A quick gander at any of the laundry list of actors who have played the titular character – Lugosi, John Carradine, Frank Langella, Christopher Lee, Gerard Butler – prove this to be true.

F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), in retrospect, serves as a subversion of the ‘Dracula’ mythos (this despite predating the various other cinematic interpretations by a decade and more). There is nothing remotely human about Max Schreck’s Count Orlock, a hideously pallid creature left alone in a crumbling relic of a mansion. It’s a terrifying rendition of the character, lacking any of the softening romanticism of later versions. Shreck’s ‘Dracula’ is a purely malevolent force often shot only in silhouette, the long shadow of his/its finger as terrifying an image as has ever been captured on celluloid. The depiction so unnatural and foreign – it would even later inspire a movie about how Schreck really was a vampire (the Willem Dafoe starring Shadow of A Vampire).

But Herzog isn’t content to merely recreate and homage Murnau’s masterpiece. His Nosferatu subverts the very subversions of its predecessor by demythologizing the monster. In Herzog’s film, Dracula isn’t the de-rigueur Übermensch Tragic Romantic Hero nor is he Schreck’s Waking Nightmare. To Herzog, Dracula is a creature not to fear or aspire, but to pity – a pathetic loser cursed to live for eternity with no one to care for.

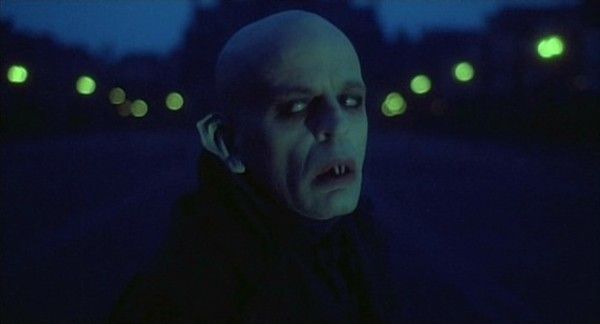

Klaus Kinski, working with Herzog for the second of what would be five times, projects a sly vulnerability to his Count Dracula. Often it’s hard to tell whether or not Kinski wants to bite into the neck of his prey or have a good cry on their shoulder. With his buck-toothed fangs, splotchy pale skin and bulging veiny forehead, Kinski’s Nosferatu strangely brings to mind the image of the stereotypical ‘nerd’ -- the type who’s spent all his time in his mother’s basement playing video games and now has no understanding of daily hygiene or how to carry a conversation with anyone other than himself. Take an early scene between Kinski’s Nosferatu and Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz): Harker dines on food while Kinski stares at him in the chair nearby, his head stretched out like a bird, never blinking. It’s as if someone once told Dracula that when you have a guest over, you should be attentive – and then he took that advice to the most extreme measure possible. The poor guy lacks any degree of social decorum – and yet he tries so very hard, offering Jonathan a meal, pouring his glass with wine, making the most strained dinner conversation imaginable, all leading up to an uncomfortable moment where Jonathan cuts his finger and Dracula sucks his thumb to, you know, quell the bleeding.

Herzog contributes to the overwhelming awkwardness of the scene by playing it in a mostly long static two-shot. A quick shot of Dracula staring, eyes-wide-open, would undoubtedly be a creepy image; but imagine now holding that shot for over a minute – and then adding the object of his gaze (Jonathan) to the foreground, blithely eating away unaware. All of the sudden what on the outset appears to be a terrifying image (a vampire studying his soon-to-be prey), becomes comical in its strange juxtaposition.

Herzog later employs his static long takes for equally bizarre comic relief as Dracula sets off to prowl the night. He whisks his cape to the side and runs off, crouched like a bat -- except the camera lingers right at the starting point, so instead of moving with Kinski and feeling whatever rush Dracula feels in that moment, we (the camera and by proxy the audience) watch as this strange ashen man in a much too long cape crab walks as quickly as possible into the far distance. Never has immortality looked less cool – which is exactly the point Herzog is driving at, suggesting the only alternative to death is to become a complete and total shmuck.

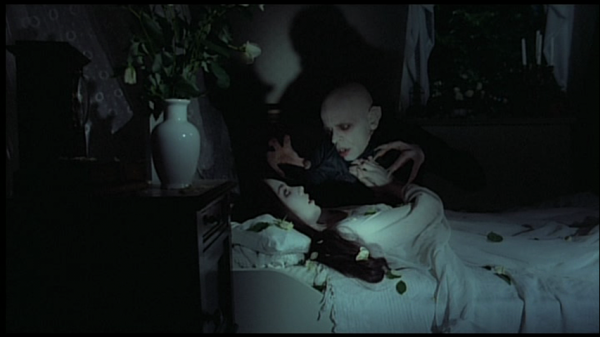

Herzog’s film climaxes with Dracula’s ‘seduction’ of ‘Pseudo-Mina’ Lucy, except here (much like it was in Murnau’s original), it is Lucy who does the ‘seducing’ – a veiled ruse to keep Dracula out until the sun comes up and vanquishes him. This switch in the gender dynamic tilts all the power to Lucy, rendering Dracula’s supposed virility moot. The most telling moment occurs after Dracula has entered into Lucy’s bedchamber. The creature towers over her, ready to bite in. Lucy, in her soon to be last moments, naturally resists -- hands pressed out begging for mercy. Dracula hesitates. He looks downward towards Lucy’s nightgown and then lifting it up with one of his talons, exposes Lucy’s bare legs underneath. This immediately prompts Lucy to grab hold of Dracula’s head, turning him away from her exposed self. She instead presses the vampire’s head onto her neck, allowing him to feed off her. The prospect of some sort of sexual dalliance so unwanted, Lucy would rather have the bloodsucker eat her instead-- the moment emblematic of Herzog’s total rejection of Dracula’s supposed carnal prowess.

By creating such a ‘lame duck’ Dracula, Herzog casts shade onto the very notion of immortality. The self-evident allure of ‘living forever’ deconstructed and laid bare by Herzog’s bleak view of living. What good is eternal existence when life itself is inherently such a drag? Even heroes Lucy and Jonathan at the outset of the picture are completely miserable. Sharing separate beds, Lucy is plagued by nightmares and prone to openly lamenting that she wishes things were like how they were “before”; meanwhile Jonathan can’t wait to get out of the house, his business trip to see the Count Dracula merely an excuse to get away from Lucy for an extended period of time. It’s not that these people are stuck going through the motions of living – it’s that there’s no other alternative. All one can hope for is to go through the motions. Life is an act of pretending, pretending that your choices count, pretending that you’re significant, that you’re an individual, that things – that you – matter, forgoing the only truth there is: that you will die and be forgotten and everything you think you’ve done of consequence will hold absolutely no bearing on anything.

After Van Helsing (Walter Ladengast) has dispatched of Kinski’s Dracula in Lucy’s bedroom, he returns downstairs – two town officials there waiting for him. One of the officials orders Van Helsing to be put under arrest for murder. The other gently chimes in that Van Helsing can’t be put under arrest because the entire police force is dead, as are the prison guards. The brash official insists Van Helsing MUST be put under arrest immediately. His reluctant partner finally relents and escorts Van Helsing from the home, confiding as he does so, “I don’t know where I’m taking you.” Van Helsing responds nonchalantly, “Take me wherever you want.” And so the two leave under the pretense of prisoner and official, going to a place neither know nor care much about, going through the motions, pretending to exist.

A 35mm print of Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht is currently playing at the Cinefamily through May 22nd. A newly restored Blu-ray of the film will be released by Scream Factory May 20th.

**Herzog switches the Mina character to Lucy and the secondary Lucy character to Mina – perhaps a tip-off of sorts that what you’re about to watch is the ‘bizarro’ alternative version of the classic Dracula story. Up is down. Down is up. Mina is Lucy. Lucy – Mina.