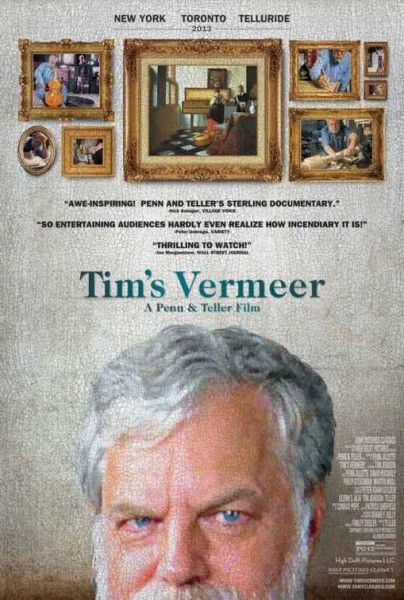

Penn & Teller’s acclaimed documentary, Tim’s Vermeer, is not the first look into Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer’s likely use of optics in his work but it’s certainly one of the most fascinating. Produced by Penn Jillette and directed by Teller, the film focuses on visionary inventor Tim Jenison’s meticulous research into how Vermeer was able to paint so photo-realistically 150 years before the invention of photography. Unlike most documentaries, they had no idea at the start how it would turn out. The most intriguing aspect is watching Tim’s attempt to prove his hypothesis by painstakingly recreating Vermeer’s The Music Lesson using only the tools and materials Vermeer would have had available in the 17th century.

In an exclusive interview, Jillette spoke about his longtime friendship with Tim, the unexpected way the project emerged, why Teller and he decided to make a movie about Tim’s investigation and finance it themselves, what makes their documentary so unusual, the decision to focus the film on Tim, the concept of genius and how the term is often misused, and why they like the fact that the film celebrates the idea of just doing something. Jillette also discussed his new horror movie, Director’s Cut, directed by Adam Rifkin. Check out the interview after the jump.

QUESTION: What inspired you to make a film about Tim’s attempt to uncover one of the great mysteries in art? How did this project first come about?

PENN JILLETTE: Tim and I have been friends for 25 years. We’re very close friends. We’d never worked together and never intended to work together. We never would work together. Our lives don’t overlap that way. Tim is a technology guy and I’m carny trash. I was out in Vegas, and I’m an old father so I have two young children. I realized I’d gone a few months without having talked to anybody outside of my family or outside of being paid. Everything was either work or my family. I called up Tim. Tim now claims that it was a desperate call, but I didn’t remember it that way. I just said, “Tim, I’ve got to talk to a friend about something else. Not work.” So Tim flew out that night from Texas to Vegas. When I called him in the morning, he was there by 5:00 and we went out for a nice big hairy steak because we’re in Vegas. I gave him a task. I said to him, “Tell me about something that has nothing to do with my job and that I can’t possibly work on. Give me something that has nothing to do with me at all.”

Tim took a breath and said, “What do you know about Vermeer?” I knew the first page of Wikipedia, probably less than most people, but I knew a little something. I had seen a Vermeer show about five years earlier, but I’m not really an art guy. I have friends that are, but I’m not. Tim started telling me and then he showed me the video of his first oil painting. And that gasp that the audience does when they first see it [in the film], I did that and said, “What are you talking about? Are you talking Ragtime?” “No.” He told me he was going to build an exact copy of Vermeer’s room, tear down a wall in his warehouse in San Antonio, and then he was going to use a machine that he thinks he reinvented to paint a Vermeer, not a copy of a Vermeer, but his own Vermeer.

I couldn’t believe how badly he had failed at telling me something that has nothing to do with my job, because I said, “Well don’t do anything. Don’t do a thing. Stop everything and let’s document this.” And Tim said, “What are you talking about? This is going to be one paper and a YouTube video. I’m not going to document this. No one cares.” And I said, “I think they do, Tim. I think they do.” I tried to shirk the whole job. I took Tim here to L.A. and to New York. We went to all the places you expect us to go to -- Discovery, National Geographic, the BBC -- and said “You guys should do a documentary on Tim making this.” I wanted to just walk away. Throw Tim in an office and maybe have special thanks to Penn & Jillette at the end. Maybe get the voiceover gig, but just walk away.

Because I’m the one that brought Tim in, some people thought they were being punked. And those that did understand it, it just started seeming like it was shallow. They’d say, “Oh, so anybody can do it. You just take someone off the street and they can paint a Vermeer. So Vermeer wasn’t really a great painter.” And I said, “No, no no.” Finally, Tim and I were having lunch after having ten of these meetings. My manager tells me we were very close to selling it, but I pulled the plug. I just said to Tim, “Fuck it! Let’s just do it. Let’s just buy the cameras and do it.” And then shortly after that we brought Teller in as a director because I have no talent for directing at all.

Once you decided to make the film yourself, how did you approach it, especially since you had no way of knowing when you started what the final outcome might be?

JILLETTE: We put cameras all over. The interesting thing about this movie to me, one of the many interesting things, is it’s supposed to be about 17th century technology, but it’s really about 21st century technology as well, because this movie would have been impossible 15 years ago. It would have been more expensive than any movie ever made. There’s more footage than all of Apocalypse Now and all of Days of Heaven put together times a hundred. Whatever it is, it’s thousands of hours. We covered every brushstroke on three to nine cameras. There’s no brushstroke done with less than three cameras. Some were done on nine. There’s no time paint goes on the canvas without being covered by at least three cameras. You’ve got to run that over in your head. If you’d done it 15 years ago, once a week a crew would have come in and lit it. He would have painted a little bit, and they would have gone away. Maybe you’d have a still camera going, too. We were able to give to Patrick (editor Patrick Sheffield) the most footage I believe that’s ever been given on a movie.

What do you think distinguishes your film from other documentaries?

JILLETTE: It’s a different thing because there’s the stunt stuff that Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock do where they do this thing for the camera. And then, there are documentaries that talk about an event where they interview people who have experienced it and do re-creations. But it’s very hard to think of a documentary that really is a document. It’s really a document of what’s happened. It’s not a selfie. It’s not Tim talking about his hopes and his dreams and confessions and fights with his wife. It’s not those kinds of emotional things. It really is high minded, thinking about art and philosophy, and about work, just down and dirty, dumb ass work – mental work, physical work, just going through it.

When did you decide the film should center on Tim and how did you know that he could carry the movie?

JILLETE: Teller and I didn’t know. I love Tim so much, and he’s been a great friend, but we all know people we find fascinating that wouldn’t be the subject of a movie. We had all sorts of protection. We were going to do Penn & Teller wraparounds. We had all sorts of plot stuff and heavy narration, and we’d be going here and we’d cover this. And then, the more we saw of it, the more we thought Tim really is holding the screen. Most of the project was just writing us out of it. I’m still in it as the wacky next door neighbor. I’m the friend who can say some things Tim can’t say, but I’m in the movie 10 minutes and that’s the right amount. For the rest of the movie, you’ve got obviously David Hockney and Martin Mull and Professor Philip Steadman. But really the whole movie is Tim. I think, and the audiences have borne this out, that he really does hold it. They don’t need someone. The joke that I make, and it’s not even a joke, it’s just reporting, is that when we do the Q&A’s at the movie theaters, the question asked by everybody before the show is, “Will Penn & Teller be at the Q&A?” And the question asked by everybody after the movie is, “Why are Penn & Teller at the Q&A?” (Laughs) It really does work, because by the end of that movie, you care a lot about Tim.

This film is very engaging because we’re never sure how it’s going to end or if Tim will succeed in proving his hypothesis. What do you think it is about the collision of art and science in Vermeer’s work that audiences find so fascinating?

JILLETTE: I think that artists, and I mean that in a very broad sense, are very, very lazy and guarded about talking about what they’re really doing. I’m kind of plagiarizing Teller here a little bit. We throw the word genius around. Bob Dylan’s a genius. And Bob Dylan’s a genius because we don’t want to think that Bob Dylan is doing this stuff because he’s willing to work harder than we are. (Laughs) We’ve all seen Bob Dylan’s notebooks. We all know the thousands of hours he’s spent on stage. We all know that Bob Dylan isn’t known for his guitar playing, but he practices guitar playing thousands and thousands of hours. We tend to throw that word genius around to say we can’t do this so why don’t we just sit on our asses and watch TV. We also throw this other word around. Teller just said this beautiful thing last night: “Obsession is a word lazy people use for determination.” (Laughs) I think that the people who are called geniuses are willing to keep that going because there’s something kind of prosaic at first blush about saying, “Well, I just worked really hard.”

What this movie does is celebrate something that Teller, Tim and I all believe very strongly, which is “just do it.” It took Tim five years. I love the reaction that people have when they come out of this movie and say, “I’m going to go and …” whatever it is. “I’m going to go build that cabin. I’m going to go do that.” It’s not very me generation stuff. It’s not like, “Yeah, I’m good. Whatever I do is great. I’m going to just…” Tim doesn’t spend any time doing that Tony Robbins’ “I believe in myself.” He just paints the dots. I just think that we all know that “If you believe you’re great, you can do it” is bullshit. We all know that’s a lie. We all pretend that we’re the only ones that have the doubt about that. Tim kind of showed that. Tim certainly by IQ definition, and by a lot of other definitions, is a genius. Who cares? The real thing that matters is he sat with that mirror breaking his back and doing it.

Also, it’s the fact that work is not something to be avoided. It’s glorious and fun and terrific. Even the sadness of Tim being stuck in that room forever is just really you get lost in the flow. The movie reminds me of how much fun it is to work on something. Teller and I have been working together 38 years, and we have projects that we have that take us ten years to go through. I mean, this movie took us five. We have tricks we work on for ten years. I love that. It’s funny that the push back is people, especially who haven’t seen the movie, I should say in fairness to them, tend to say, “Well this is Penn & Teller debunking Vermeer,” and we go, “No, it’s about as far from that as you can go.” If you come out with a diminished view of Vermeer because of this movie, you’ve really missed the point of the movie. Fortunately, people aren’t. We’ve had one or two blogs that have said, “Well they’re just not good enough to realize how good Vermeer was.” I think that if there’s one person who understands how good Vermeer was, it’s Tim.

With Tim doing all the stuff that’s just so purely crazy, like grinding his own lenses and making his own paint and really getting into that world, there’s a sense of this that’s just time travel. I mean, you have a conversation that Tim is having with Vermeer over 350 years. There’s that document. They find the seahorse smile. They find all this stuff that Vermeer has gone through and all the art critics that look at it and say that this was what Vermeer was doing. They don’t understand it the way Tim does. And that nutty thing that you never expect, which is if you use the technique Tim came up with, San Antonio and Delft are the same. There’s nothing magic about the location. It just has that beautiful look. Tim did not do the layout of the room. Once we decide that photography is art, the whole art or not art question of this movie has been solved. The composition of the painting is Vermeer. It’s not the exact composition because Tim had everybody move in the room. He didn’t want to do a copy of the Vermeer. He wanted to have it like the way we described it as a few frames later in the shoot. The gentleman is turned and his daughter is turned aside from where they are.

Was it hard to get the financing for this?

JILLETTE: No, there was no financing. We just paid for it. Yes, it’s an expensive documentary and it tapped us out, but we did it. I mean, it’s not a romantic story of someone mortgaging their house because we’ve had more success than that. It wasn’t money that we had to sacrifice heavily for, but we still did it ourselves. It’s a happy, happy documentary.

What are you working on next that you’re excited for audiences to see?

JILLETTE: The next movie I’m doing is a movie called Director’s Cut. It’s a horror movie with me as a bad guy. It’s too expensive for me to do myself, especially when I haven’t made the money back from Tim’s Vermeer and probably won’t. It was an expensive movie, but we’ll make most of it back. And then, I’m crowdfunding. And it’s a movie about crowdfunding. It’s about a person who crowdfunds a movie and turns out to be a kidnapper and takes over the movie. We crowdfunded that and I’m doing it with a guy named Adam Rifkin. Once again, I’ll be in it, but not in a major role, and I’ll be producing. I do not want to direct. I’m the only person in this zip code that does not want to direct. As we sit here right now, there is no other living human being in this zip code that doesn’t want to direct. (Laughs) I’m the one.