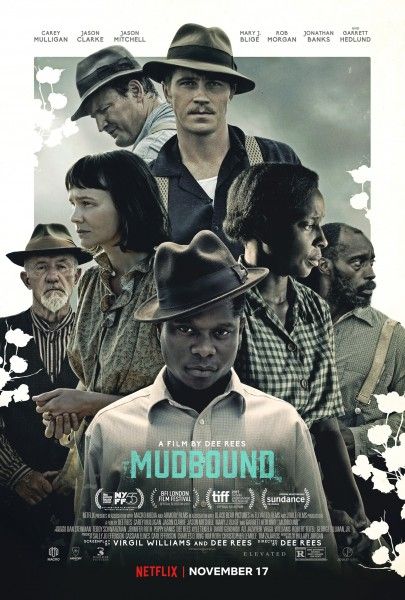

Rachel Morrison has not-so-quietly emerged as one of the most exciting cinematographers working today. While she had previously shot a number of short films, documentaries, and even the MTV series The Hills, Morrison first started making waves as a director of photography with her work on Zal Batmanglij’s thriller Sound of My Voice, and broke out in a big way with Ryan Coogler’s terrific 2013 debut Fruitvale Station. Wearing her documentary influences on her sleeve with a knack for textured and deep frames that accentuate the most human of characteristics, Morrison went on to shoot films like Cake and the colorful Dope, but her best work to date is on Dee Rees’ tremendous Southern epic Mudbound, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year and will be released on Netflix on November 17th.

Based on the Hillary Jordan novel of the same name, Mudbound takes place in the 1940s and revolves around two families—one white, one black—who live on one farm. The black family works the farm for the white family, but the stories of the characters are endlessly intertwined as they navigate racism, poverty, misogyny, and the enduring effects of slavery as World War II breaks out. The film is a triumph—a rich, deeply felt, and gorgeous chronicle of family life with strong parallels to some of the same issues America still faces today. And Morrison’s work on the movie is outstanding, bringing the 1940s South to life in a way that’s so tactile you’ll swear you can feel the sweet heat of a Mississippi summer on your face.

With Mudbound hitting Netflix and select theaters on November 17th, and with Netflix making a major push for awards consideration, I recently got the chance to speak with Morrison about her work. She discussed why the timely themes and the prospect of working with Dee Rees made her want to sign on to Mudbound immediately, the challenge of capturing so many points of view from a cinematographer’s standpoint, influences on the visual aesthetic of the film, shooting on digital and how she strove to bring a tactile quality to the image, the pros and cons of having your movie premiere on Netflix, and much more. And with Morrison reteaming with Coogler on Marvel’s fantastic-looking Black Panther, she also teased her work on that film, the atmosphere on set, and how she’s working to ensure Black Panther is visually distinct in the face of criticisms towards Marvel’s flat aesthetic throughout the MCU.

When I spoke to Morrison she was in the midst of shooting some additional photography on Black Panther (standard procedure for every Marvel movie) and battling a cold that had befallen the crew, but she was enthused to be able to talk about Mudbound given how hard she, Rees, and the whole cast and crew worked on the film. Morrison is wonderfully insightful and candid, and the conversation offers a peek into the process of one of the most exciting DP’s in the business. Check out the full interview below.

How did you first get involved in Mudbound?

RACHEL MORRISON: I’m trying to remember if Dee called me directly or if it was through my agent, but Dee and I knew each other from the Sundance/indie world. We were mutual admirers and when she approached me with this project I read the first draft, which was Virgil Williams’ draft, and she talked about some of the changes she wanted to make but I knew right away. Between wanting to work with Dee and then this script that was so powerful, and a period film is sort of a gift to any cinematographer, and I also just found it incredibly timely from both a race perspective and a gender perspective. It’s sort of sickening how little has changed in however long, but I felt like it was as relevant today as it was back then.

Yeah that’s kind of one of the striking things about it is as I was watching it you get kind of lulled into this Southern epic, but there’s this timeless quality to it all; everything seems so real and now.

MORRISON: Yeah, and the ways in which we’ve progressed are so much more subtle than we think they are. I think Trump was a wake up call to all of us, but the amount of repressed or latent sexism and racism and all these things, you know when you live in a liberal bubble you start to forget what the rest of the country looks like and maybe not even realize that your bubble isn’t so liberal behind closed doors, I don’t know.

Yeah then Trump gets elected and it’s like “Oh shit.”

MORRISON: Precisely.

This cast is quite large and one of the things that struck me about watching the film was how not a single character was short-changed. You get inside the head of or at least understand the point of view of each of these people, and you guys did such a fantastic job of capturing that. Was point of view something you really focused on as a cinematographer?

MORRISON: Yes I think that was the biggest challenge of the film for me. My one fear going into it is—I had one not so great experience on an ensemble cast movie only because, in this day and age people’s attention spans are not what they used to be; Altman used to get away with ensemble cast movies but they were three-hour epics, or three and a half hours even. In that much time you can do justice to a number of different characters, but when you try to make something for the modern audience, unless you’re Fincher or Villeneuve, but your time is limited, and then when you try to spread out 90 minutes over an ensemble cast oftentimes it sort of spreads too thin. Which is I think why television miniseries and series are sort of where the character dramas are now, because people can take things at their own pace.

So that was my one concern is how do you take this book that is just so big in so many different ways—it’s big in terms of the number of characters, it’s big in terms of what it’s trying to pull off, there are war scenes, there are fight scenes, and then there’s obviously quieter moments too and so how do you make that into a 90 to 100-minute movie? I think Dee did a tremendous job of allowing the audience to walk in each character’s shoes, so it’s definitely something we thought about, in any scene whose voice is it? The other thing when you have multiple main characters is it’s not always obvious whose point of view should carry the scene. To ensure the film is evenly weighted it’s a matter figuring out in this scene we want to lean into Ronsel’s voice, and in this scene do we want to lean into Laura’s voice. Sorry that was a very roundabout way of saying it was something we were acutely aware of and that was the most daunting task for me (laughs).

The book is big, and the movie is certainly a Southern epic but it doesn’t feel long it just feels rich. And I felt a richness to the image quality as well, there’s a very tactile, texturized quality to the image where you feel like you could step into it at any moment. Was that depth something that you wanted to hone in on?

MORRISON: Well thank you. Yes, for me tactile is probably the perfect word. You have mud that is sort of a character unto itself. I mean to me everything about this film wanted to be analog and unfortunately at the end of the day we just couldn’t afford to shoot on film without losing shooting days, and we didn’t have enough shooting days as it was. So ultimately we had to shoot it digitally but I was doing everything I could to breathe the analog back into it because I feel like there’s a real tactile quality to a visible, palpable grain, so I did some of that in camera and some of it in post. The way films that are about food you want the audience to feel like they can taste it, in this case I wanted to try to make the audience feel like they were walking in the mud and dealing with the elements and burning in the sun, that kind of thing.

Do you have a general preference between shooting on film? I don’t know if you shot Fruitvale or Cake on film or digital…

MORRISON: Fruitvale was film, Cake was digital. I think it really comes down to the story, and for me this story would’ve been a great one to shoot on film. But one of the things we gained by on shooting digital was being able to shoot some of the night scenes with lit candles and stuff like that, more practical lighting. So in a perfect, perfect world, if money was no object, I probably would’ve shot the day scenes on film and the night scenes on digital just to have a little extra stop and to be able to do a few more things practically, but you know I think that look isn’t right for everything. Certainly a lot of the modern day futuristic pieces it feels right to be digital and to be crisp and to have more resolution and all those things. I generally steer clear of extra resolution for a story that I want to feel tactile and palpable and humane and intimate, but I think digital works well when you’re looking at something that’s supposed to feel slick or futuristic. I think it really just comes down to the story, but I love film. I think it definitely has its place and I hope that it will always be around to offer us that as a tool.

Yeah it feels like it was on life support for a minute, but it feels like it’s coming back in a big way with things like Baby Driver and Dunkirk obviously and Star Wars.

MORRISON: I think every year though people sort of have that same [conversation]. I feel like for that last five years I’ve probably had that same conversation where somebody said, ‘It feels like it was on life support but then look at all these films.’ There was one year where I think eight out of nine of the Oscar-nominated films were shot on film. Maybe they were the only eight films shot on film that year, but I think it does kind of find a way to keep itself going because we need it.

For sure. I’m curious, what were your early conversations with Dee like about Mudbound? Did you hit on a specific visual theme or approach?

MORRISON: We talked about a bunch of different references, and she introduced me to the documentarian Les Blank and we looked at some of his work and the organic camera movement and naturalistic lighting and the color palette to some extent. And also to Whitfield Lovell, who’s a contemporary artist who does a lot of portraits on wood. I think if you look at the Jackson story there’s a real wood theme and color palette to it. I brought to the table a lot of the Farm Security Administration photographers who have been influential to me for a long time before this even came along, but it was just a nice opportunity to do something a little bit in the vein of that world and period. And also Gordon Parks, there’s some of his work—actually a little bit later work, but some of his color work I found to be very influential to the color palette. But for me I was really trying to find a way to denote the period but without feeling like you sort of hit the tea stain button or everything’s sepia toned. The other trend as of late, which I feel is becoming so overused, is the milked-out look where everything is a little bit desaturated. I feel like especially with these skin tones I didn’t want the blacks to be brown, I wanted the opportunity to have rich blacks and still have something that felt of a different time period. So the initial jumping off point was looking for a way to still have colors, still have blacks, but maybe not as poppy as they would be now.

There’s also a real dynamism to the imagery. The story covers a lot of ground where you’re on the farm life but then you go to Europe and cover World War II and fight sequences. Was it daunting to tackle this variety of settings or was that more of an exciting prospect for you?

MORRISON: I would say the prospect was exciting, the reality of our time constraints made it daunting. That prospect with 10 more days in the schedule would have been nothing but excitement. That prospect with what we had, which was like 28 days total, was both exciting and daunting.

Wow, I mean you pulled it off. I can’t believe it only took 28 days. It looks fantastic.

MORRISON: Thank you (laughs). I of course would look at the few scenes where I would have loved to have had more time to finesse a bit, but hopefully the story transcends the speed at which we shot it.

Well the way people are watching films and television is changing, and obviously Netflix is a big part of that. How do you feel about the fact that most people will be watching this film on television rather than in a theater?

MORRISON: I’m conflicted. I mean honestly I’m excited by the prospect that it will be available in so many homes, and Netflix is sort of—not everybody has Netflix, but there is a real opportunity to reach an audience who might not have made it to the theater otherwise. So that part’s really exciting. It wasn’t a Netflix original movie so I didn’t have small screen in mind when I shot it, and that’s always a little bit—disappointing isn’t the right word, but when your intention and the actuality aren’t congruous you just have to sort of wrap your head around it. It’s probably better than the other way around. I remember seeing Confirmation, which was always intended to be for HBO and small screen, and the theatrical premiere of it—it’s exciting to see on the big screen but oh my God, there are things that it was just never intended to be seen on the big screen. So better to intend for the big screen and be seen on small other than the other way around. But, ultimately I guess it’s exciting. I hope it does reach a much wider audience as a result of being on Netflix.

Yeah the access is huge. Switching gears for a minute, I have to tell you it’s been a really long time since I’ve felt the kind of electricity around trailers for a movie that I do for Black Panther. Everyone is going nuts for this thing and it looks absolutely incredible. And with you shooting and Ryan Coogler directing and that cast, it’s insane. What’s the experience been like for you, making this huge superhero movie with such a talented group of individuals?

MORRISON: It’s been exciting. For me, I always like new challenges and so the chance to do something that’s just so completely outside my wheelhouse is welcome in a way. I didn’t know what to expect myself because these aren’t the movies I watch, although now of course I’m a huge Marvel fan. I’m still a drama girl by all means, but I have really enjoyed sort of soaking in the process. And at the same time as you would imagine from a Ryan Coogler film, it never felt like the formula. It just felt like we were making a gigantic indie movie. And in a crazy way there’s still never enough money and never enough time. The things you imagine for what those tentpole movies are like, it’s somehow just a ginormous version of an indie. Even today, we’re doing pickups right now, I think I had 10 pettibones with 30x bluescreens on them and we needed 12. That never changes. I probably had 12 grips on the roster and I need 14. The bigger the movie gets, the problems just kind of escalate in the same way (laughs).

The numbers get bigger but the proportions are the same.

MORRISON: (Laughs) Exactly. But the energy around the trailer has been really exciting. Now I just hope we can live up to the hype. The nice thing about being the underdog—I remember Fruitvale going to Sundance and nobody was talking about that movie, it was so understated. There was no hype around it, so it was like this surprise discovery. Suddenly I’m on the opposite end of things where it just feels like there’s so much hype around this film that I think the anxiety’s gonna be whether we can live up to the expectations.

There’s a criticism that there tends to be a bit of a sameness to the visual palette of some Marvel movies. Was that ever a point of discussion with you and Ryan and Marvel, about making Black Panther really distinct?

MORRISON: If there’s anything consistent about my work it’s not flat. The criticism of Marvel movies whether it’s in the cinematography or in the Digital Intermediate is that sometimes sort of lack contrast and saturation. That certainly isn’t true of my work from the outset, so hopefully the look we’re presenting will hold through to the end. But I think in making something so big, if you take for example an exterior day scene that’s shot over 15, 20 days you’re not gonna have all sunny days so what happens at the end of shooting when it’s half sun and half cloud. The natural tendency is to lean into something in the middle, to kind of flatten out the contrast on the sunny day and maybe try to bump up the contrast on the cloudy day and find somewhere to meet in the middle. That was my biggest concern going in was that we don’t allow that to happen, so we would throw hard light at people on cloudy days just to kind of increase the contrast.

Well I can’t wait to see it. My last question for you, I know you’ve directed a couple of times—is that something you’re looking to do again? Would you ever pull a Soderbergh and shoot your own movie?

MORRISON: Maybe. I wouldn’t rule anything out. For me I just like new challenges. Directing came up kind of out of the blue to the same extent that Black Panther came out of the blue. Directing, I’d had an amazing conversation with John Ridley at the Indie Spirit Awards a few years ago and just based off of this conversation and the sheer coincidence that I had shot a bunch of commercials so I had something to show, he had called and said, ‘I think you’d be great as a director, do you have any interest in this?’ So I was very fortunate that I was pulled out of nowhere to go and direct some television for him, and for me at the time it was just exciting to try something different. I was shooting all sorts of smaller indie movies, I wasn’t getting calls from big studios at the time—not that studios are the be-all, end-all, but that was the clear point of growth for me so I just felt like I was putting out the same fires, and I got the chance to direct something different. Now I’ve been able to put out some new fires by doing bigger movies, by doing period movies, by doing something a little bit different. I definitely think I’ll direct again. I love shooting so that’s something I never wanna give up entirely. I think there’s this assumption that everybody would rather be a director, and I don’t know that that’s the case for me so we’ll see.