Cedric Diggory died in a cemetery, fatally cursed by a rodent sorcerer. If he had committed a crime, it was nothing more than being Harry Potter’s skilled competitor in the Quidditch league and a fellow Hogwarts student. In fact, nothing less than his most thrilling and triumphant win as a promising young athlete leads him to the place where he perishes. Mr. Pettigrew and his boss are to blame for his death but had Diggory not been a popular Hogwarts pupil on a similar social and athletic level as Mr. Potter, the proud Hufflepuff would have likely lived on. His greatest victory as a popular schoolboy pushed him toward unrelenting darkness.

Even if Robert Pattinson hadn’t played Diggory in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, someone familiar with both the character and the actor could have easily sussed out a connection. After graduating from the same independent schools that produced Tom Hardy and Will Poulter, he took to the London stage but by 2005, he had secured his role in Goblet of Fire. Three years later, he would read for and cinch the role of Edward Cullen in a series of movies adapted from Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight and from there, he would become an unexpected heartthrob and a bankable leading man. Around the time the first volume of Breaking Dawn came out, he would co-star with Reese Witherspoon in Water for Elephants and appeared in the umpteenth adaptation of Bel Ami. Neither caught on at the box office, nor were they celebrated by critics.

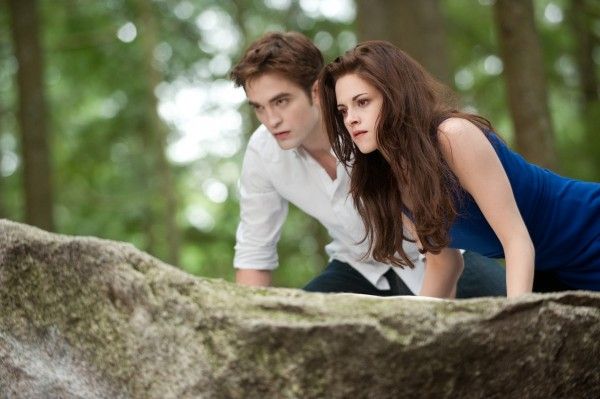

In 2012, the concluding chapter of the Twilight franchise was released to middling acclaim, and three months earlier, almost to the day, David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis received a limited release. The latter’s domestic take was a noticeably shy of $800,000, while Breaking Dawn – Part 2 made well over $292 million. In the latter film, Pattinson struggles with admittedly obvious and often clunky dialogue amidst an egregiously convoluted plot, and it often feels as if his job is to strictly pose and recite. He gives his physique to the role in full but there is no sense of inner life or convincing internal processes.

In contrast, part of what makes Cosmopolis so eerie and insidious is how you can almost see Pattinson’s alpha-capitalist’s reptile brain at work. Some have wrongly passed it off as computer-like and mechanical, tied to his character’s connection to industry via his home away from home in his stretched white limousine. There’s something far more messy and dominant bumping around underneath his façade, but we’re always aware of his psychological and biological works turning and grinding away. He sees getting a haircut as a necessary allotment of time for “associations,” amongst a life of isolation in a roaming Lincoln Town Car. As society seems to be collapsing around him, Pattinson’s man checks in on his business, has a quickie with a journalist (Juliette Binoche), and works on purchasing the Rothko Chapel, just because he can.

Whereas much of the Twilight movies hinged on Pattinson standing, staring, or vaguely undulating while talking fantastical nonsense, Pattinson is on the move for much of his new movie, Good Time, in which he plays Connie Nikas, a low-level New York City hustler and bank robber. When we first meet him, he engulfs the already sensitive discussion between his mentally disabled brother, Nick, played by co-director Benny Safdie, and his therapist (Peter Verby), prying Nick away to commit armed robbery. Pattinson is urgent without tipping over into frenzy, constantly looking for an easy fix and a quick buck. Even in the confines of a bail bondsman’s office, he all but paces up and across the ceiling while waiting for his girlfriend’s credit card to go through.

Pattinson’s role in Good Time, the best American film to be released this year thus far, will likely be remembered as the performance that almost led to him making a dog ejaculate but it deserves much more than that remarkable bit of trivia. Pattinson’s liberated, endlessly watchable performance is matched in kind by the Safdie brothers’ radical, limber style, alongside electrifying, intimate camerawork by the great Sean Price Williams, and a disruptive, entrancing score by Oneohtrix Point Never’s Daniel Lopatin. In the whirl of illegal hijinks that brings Connie into a scheme to sell a Sprite bottle full of acid and break Nick out of his police-guarded hospital room, all these elements play in disjointed concert with one another. Pattinson, regularly sweaty and cursed with dyed hair that makes him look like the preachy original bassist that Fred Durst kicked out of Limp Bizkit, mirrors a desperation in the filmmakers to get their New York-set fever dream financed and made while maintaining familial bonds and self-care. In the moment, however, Pattinson’s darting, rapid glances, his rambling tirades and long-form, self-centered excuses to friends and strangers, and blurs of frantic violence and gestures are nothing less than pure cinematic thrill, rushing through the viewer like a hit of adrenaline.

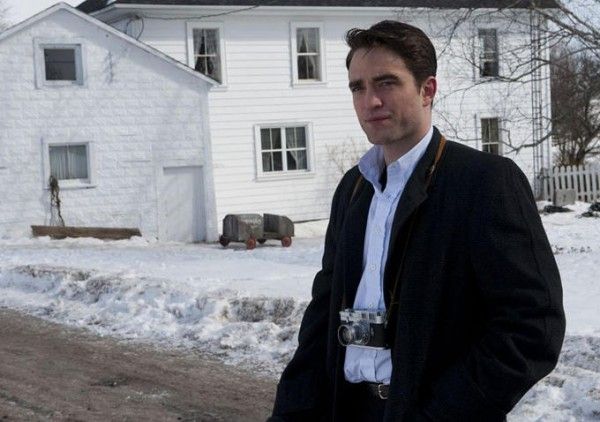

For all of his faults as a brother and a good neighbor, Connie is a skilled problem solver, good on the spot and entirely indifferent to what happens in the aftermath of his decisions. In his mind, he’s a genuine star and that’s a sentiment that has never been embedded in any of his previous performances. In Twilight, he is only illuminated in the presence of Kristen Stewart’s Bella, whereas in Cosmopolis, he is a star who wants no attention and only limited connection to tothers. In The Lost City of Z, he’s the able and mysterious second-hand man to a world-class explorer, around for the adventure yet never in the spotlight. Anton Corbijn's largely unseen Life has him as the quiet Life Magazine photographer Dennis Stock to Dane DeHaan's James Dean. He speaks exclusively in wheezes, whispers, and mumbles in David Michôd’s grievously undervalued The Rover.

The only other movie that shows Pattinson in the ambitious mode is his least lucrative project, Cronenberg’s much-maligned Maps to the Stars. Here, he is the one driving around the fancy car, playing wheelman for Julianne Moore’s washed-up starlet. For all his hopes, it’s made relatively clear that Pattinson’s driver will spend much of his life driving celebrities around while never becoming one, occasionally landing a stray lay or a bit part on some nothing program. If Pattinson needed to wash the taste of Hollywood out of his mouth, Maps to the Stars provided the occasion, and the abysmal box office receipts seemed to be reflective of that attitude.

The 31-year-old actor has made it clear at this point that he’s only interested in working with directors he genuinely wants to work with at this point and that doesn’t look to be stopping. His upcoming projects include teaming with French master Claire Denis, she of Bastards, 35 Shots of Rum, and White Material, and David Zellner, who is working on his follow-up to Kumiko, the Treasure Hunter. Though he has substantial financial comfort and already came from a well-off family, there is still an unmistakable hint of rebellion and unyielding dissatisfaction with populism that denotes Pattinson’s turns in his career. Good Time, however, is the first time that this rebellion seems to be engrained in the fabric of the movie, inseparable from the unwieldy detours through New York’s lightweight underground. Under the Safdie brothers’ direction, Pattinson seems more like himself than ever before, even while playing someone who seems as far away from Pattinson’s day-to-day personality as a teenaged wizard.